It's been hiding in plain sight for decades but now the Royal Commission on Abuse in Care has confirmed what many have always known - a major percentage of those who went through the welfare system as children ended up filling the country's jails. Aaron Smale reports.

Rangi Wickliffe and Tyrone Marks were in Owairaka Boys Home together in the 1970s and went straight from there to prison. And now a Royal Commission has found that around 30 percent of children who went through state-run welfare homes ended up in jail.

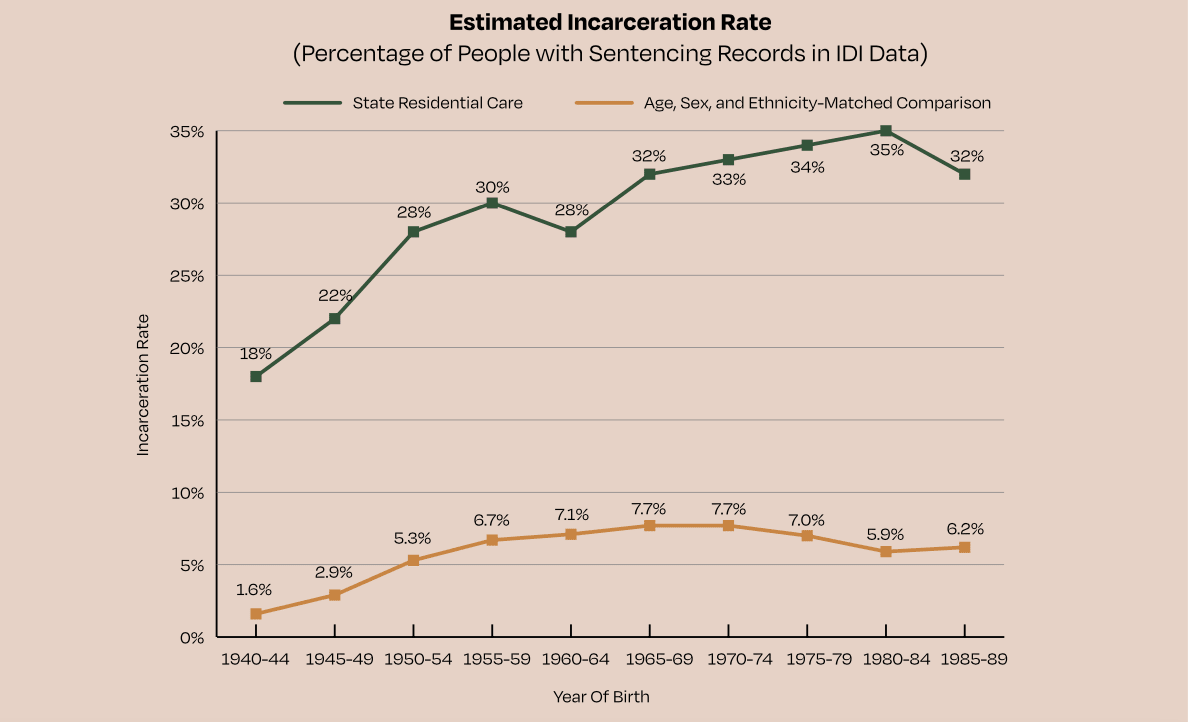

A research report carried out for the Royal Commission matched names from a sample of more than 30,000 children who went through state welfare homes between 1950 and 1999 with data from Corrections. The research found that "one in five and, sometimes, as many as one in three of those children and young people who had been in state residential care, went on to serve a criminal custodial sentence later in life. This is a much higher rate than those who had not been in state care."

Wickliffe spent 35 years from his mid-teens in and out of the prison system, starting with a stint in Mt Eden when he was 14 and then being locked up in D Block in Paremoremo when he was 16. During more than three decades in the prison system he was constantly running into people he knew from welfare homes like Owairaka, Epuni, Hokio, Kohitere and Lake Alice adolescent unit. The Royal Commission's findings are no surprise to him.

After going into welfare homes at a young age Wickliffe's transition to prison was seamless.

"I'd had a long history with Owairaka. Avery (the principal) picked on me as an eight year old all the way through. He was constant. And I thought, 'Fuck, one day I'll get you.' Well, that day was when I was 14. I had enough of that c**t hitting me so I fucking laid him out."

Wickliffe was sent to Mt Eden where he was put in solitary and then ended up in the yard with two of the country's most notorious murderers, who took him under their wing.

"In Mt Eden prison as a 14 year old I went straight to solitary confinement. And then they unlock the door the next day into the yard with Ronnie Jorgensen and John Gillies (the Bassett Rd machine-gun murderers.)"

Although he found prisons violent he adapted because he'd been conditioned to it as a child.

"They're producing criminals, sending them to residential care, which is primary education and on to university, which is prison. Each step that you take in that arena you actually go up a level. You start retaliating, you start building up a reputation for yourself and everybody around you is doing the same thing."

"We go in there as little boys, we come out as gang members. You've got to ask yourself, 'Well, how did that come about?' And I keep telling everyone that's how the gangs in New Zealand were founded, they were founded by people that had come out of state care. Society rejected them as fucking scumbags, 'Ah well, we'll start a gang', and that's how it was all created. Some of the biggest serial rapists and murderers in this country have come from state care."

Marks also went into state custody as a young child and graduated to prison at the same time as Wickliffe. Although he stopped going to prison in his 20s, it took time to unlearn what the state had taught him as his legal parent. He said the welfare staff expected and predicted the children would end up in prison.

"I was reading in my welfare file a social worker says in a report that with a bit of luck I'll end up in borstal. And that's where I ended up.

"I came back from Aussie, I was in jail over there, in jail before I left, then jail again here. After that I thought, 'Fuck this, everywhere I go there's always a jail in front of me'."

Hohepa Taiaroa went through Kohitere and then Waikeria borstal in the 1970s and says the incarceration was as much psychological as physical. He says the violence and solitary confinement he experienced in Kohitere as a child led to him self-isolating and building a protective wall around himself because he couldn't trust anyone, not even his family.

"You can be a criminal, or you can be a father, but you can never ever be both."

"Out of that came loneliness. I understand that quite well. And you learn to live with that loneliness, because that's all you had. You didn't trust anybody, even your own people. You didn't trust anybody. After that initial shock, it's like you close right down.

"You might look normal outside, but inside you're like a hurricane. That's how bad it is. When you get into that state, you just can't trust anybody. Even your own family, your kids, your missus. We can't trust anyone."

Taiaroa says the path that the welfare system sent him on robbed him of his ability to be a good father.

"The education that we got was only to improve our criminal activity. So it was highly likely that we were going to be incarcerated in the near future. You can be a criminal, or you can be a father, but you can never ever be both."

Emeritus Professor of Law Jane Kelsey says the Royal Commission's report is no surprise, but points out that successive governments have ignored report after report that has been saying the same thing for decades. She called it an "orchestrated institutional amnesia."

"It's not as if there hasn't been a lot of writing. All of the information and analysis was laid bare in the 70s, 80s and 90s. There's been this orchestrated institutional amnesia about all of that work and all of a sudden now we've got the Royal Commission, 'Oh, gosh, isn't this terrible?' Well, who's responsible for having suppressed that information and the action on it and at the cost of those who were the victims and the generations of them? It's not it's not a cost-free amnesia."

Kelsey says the state has refused to recognise its own institutional racism despite thinkers like Moana Jackson spelling it out in the 1980s and successive reports and royal commissions telling the government the same thing.

"That's why it was always called institutionalised racism. It's not about the personal prejudices of individuals. That's a superficial element of what is a fundamental structural feature of how the state has operated towards Māori. And if you go back to Moana Jackson's Whaipaanga Hou (Criminal Justice report) you can't not trace it to colonisation and dispossession. There's also the report that Aroha Mead did on Te Puao Te Atatu about the social welfare system, and even the Royal Commission on Social Policy. So that was throughout the 70s, and 80s all of this was laid bare. There was active neglect, active denial by the state. And when you look at the evidence that's been given today in the Royal Commission, you can see the role of the lawyers behind it, saying, 'minimise legal risk of liability in what evidence you give'."

Kelsey believes the government has repeatedly ignored the evidence that has always been there because "it opens a Treaty of Waitangi Pandora's box".

"(Minister of Justice) Geoffrey Palmer wanted to have a report on why there were so many Māori in prisons (in the 1980s). And he wanted a kind of a micro explanation. And Moana gave him the explanation. But Palmer wouldn't even write the foreword for the report."

The Royal Commission's report has several caveats qualifying the statistics, but even these limitations in the data tell a story, says Professor Tracey McIntosh of University of Auckland.

"Everything about the report makes me sad, even the whole thing around the quality of the data. The spelling mistakes for Māori names. Date of births not been put in. In some cases, no registers. All of those things that so demonstrate a disregard of the dignity of our children."

McIntosh says the environments of the state welfare homes were very similar to prisons and many ended up in prison because they found it easier to deal with than the outside world. She has done a lot of research with state abuse survivor Stan Coster who spent a lot of his adult life in prison after going through welfare homes.

"His desire to be in segregation and seclusion in prison was because that's what he'd learned at Epuni. He was in seclusion there, first non-voluntary, but in the end, that's the place that he liked because it was a place that he could have some semblance of safety. And he kept that right through all of his adult years in prison. So there's particular ways of managing the system and being, say, a difficult prisoner, was very much learned behaviour from the state care system. It's a regulatory environment and the state care system has both hardened and inured them to it. Whereas they don't have the skills to do that in the outside world."

She says one of the skills many children in state custody learned was violence just to survive the onslaught of violence that was a part of the environment.

"The skills you learn within the state care system for survival and protection, they work well for a prison system, but they're really maladaptive for the outside world. Particularly young children's use of violence to try to halt further victimisation. So if you come into the system really young, you know, some of the ones I've talked to, and coming in at say eight years old, you're extremely vulnerable as an eight year old coming into that system when you've got 15, 16 years old, you've got a Lord of the Flies hierarchy. So as an eight year old, or a nine year old, how are you going to respond to that? You've either got to make yourself invisible, or two, you've got to harden the target. One of the things is a disproportionate response to insult so after a while you come be seen as a loose cannon. 'Yeah, stay away from that little fucker, you know, he's crazy.' People might, not every time, but might leave you alone. So you use violence to try to resist further victimisation."

McIntosh says there has been horrific evidence given at the Royal Commission but she has been disappointed at the lack of political response so far.

"People can respond emotionally to sad stories. When I do stuff I do with women, people really respond strongly to it, but they respond totally at an emotional level, not a political level. And that's the problem. So they can have empathy. But I couldn't believe it during the Māori hearings, not one Māori politician said anything."

Criminal justice campaigner Sir Kim Workman was a police youth aid officer in the 1970s and would regularly visit Kohitere Boys Home in Levin and later became the head of prisons where he saw many of the same individuals he'd seen in the welfare system. He says the report from the Royal Commission is not at all surprising and people have known about the connection for decades but have been unwilling to address it. He says he had a conversation with a senior figure in the police about the factors that influence children ending up in the criminal justice system such as the parent being on a benefit or being involved in gangs. Sir Kim was surprised that the police were not including the person's history of being in state custody as a child.

"The guy that I was talking to said, 'We don't want that in there because it reflects on the actions of the state'.

"It's becoming more and more difficult to ignore the evidence because there's so much of it. But if you look at the way in which some of the government agencies are giving evidence over the last week (at the Royal Commission), it's reflective of their avoiding responsibility."