Tobacco pipes were one of the first mass-produced, disposable objects in Britain. Through contact with indigenous peoples of the Americas, tobacco pipes and tobacco were introduced to Europe as early as the 16th century, but had been used in the Americas for centuries before this.

Pipes were adapted for European tastes using European materials, and in England the most popular material for pipes between 1600 and 1900 was clay. Shapes and styles varied over the years, but the basic design remained the same: a hand-held bowl to burn tobacco in and a stem to draw the smoke the mouth of the smoker.

Pipes were lightweight, rigid and made out of inexpensive materials. They were also rather breakable. This cheapness and breakability means they show up in large number across post-medieval archaeological sites in Britain.

The usefulness of pipes as artefacts is well established. Tobacco pipes found in archaeological digs can help researchers identify the dates when a particular site may have been occupied (based on bowl or stem size) and even who may have occupied these spaces (bite marks in stems may indicate workers holding them in their mouths while working, for example). Pipes can also inform researchers about patterns of tobacco consumption over time.

However, our research has uncovered fascinating new evidence about some of the other ways people used tobacco pipes in the past. Smoking might kill but what we found is that people routinely used tobacco pipes as weapons and as medical instruments from at least as early as the 17th century, although most of the evidence dates to the 18th century.

This new evidence brings to life the everyday experiences of those who encountered tobacco pipes. It also gives historians and archaeologists new ways of thinking about how we study historic artefacts because it encourages us to think beyond the intended functions of objects.

What these alternative uses tell us is that pipes were objects that occupied the everyday lives of men and women in the British past far beyond what we have assumed. The archaeological record has already told us that pipes were incredibly common.

By looking at evidence from archives, such as criminal records and medical texts, we understand that this commonality meant that pipes were not just used to smoke tobacco and likely played a more prominent role in everyday life than we have previously considered.

Pipes as weapons

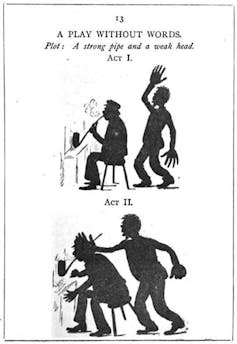

Clay tobacco pipes were hand-held and breakable. This made them ideal for striking or stabbing with when tempers flared. In about three-quarters of the cases we looked at, attacks happened when someone holding a pipe lashed out at another person. A punch to the head, face or neck could result in a serious puncture wound, cause blindness or even death if a pipe was involved.

For example, in Caernarfonshire in Wales in 1788, a man named Sylvanus Owen was found guilty of manslaughter for striking another man with his right hand. The punch proved fatal because Owen had two pieces of a clay pipe in his had at the time, one of which entered the other man’s eye, causing a serious infection.

We also found pipes being used to intentionally burn others and as shot in pistols.

Pipes as medical instruments

Some of the same properties that made pipes excellent impromptu weapons also made them useful improvised medical instruments. The ready availability of pipes meant that one was likely always to hand and the long, narrow stems and wide bowls meant they had several uses beyond smoking.

Evidence from medical publications such as the Lancet and surgical guides suggest that pipe stems could be used as catheters to relieve both men and women of retained urine.

Pipes were also recommended for emergency tracheotomies, as straws for those who could not eat and drink on their own, and as lactation aides for nursing mothers. In 1796, Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles Darwin) even recommended using the stem of a tobacco pipe to remove a guinea worm (a waterborne parasite found in certain parts of Africa) from an infected patient.

As both weapons and medical instruments, it was the combination of clay tobacco pipes’ properties and availability that made them ideal improvised tools. There is an obvious and interesting contradiction that one alternative use was to harm or end life and the other was to improve or preserve it.

Sarah Inskip receives funding from the UKRI-AHRC.

Angela Muir does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.