ONE HUNDRED years of serving the community, thousands of hours in the sky and a handful of jobs that won't ever leave them.

Graham Nickisson, Peter Cook and Glen Ramplin, better known as 'Nicko', 'Cookie' and 'Rampo', have between them helped keep the Westpac Rescue Helicopter in the air for a century.

The trio sat down together with the Newcastle Herald to talk about the trauma and the danger, the families and call-outs that stick with them, and the mateship that still tethers them.

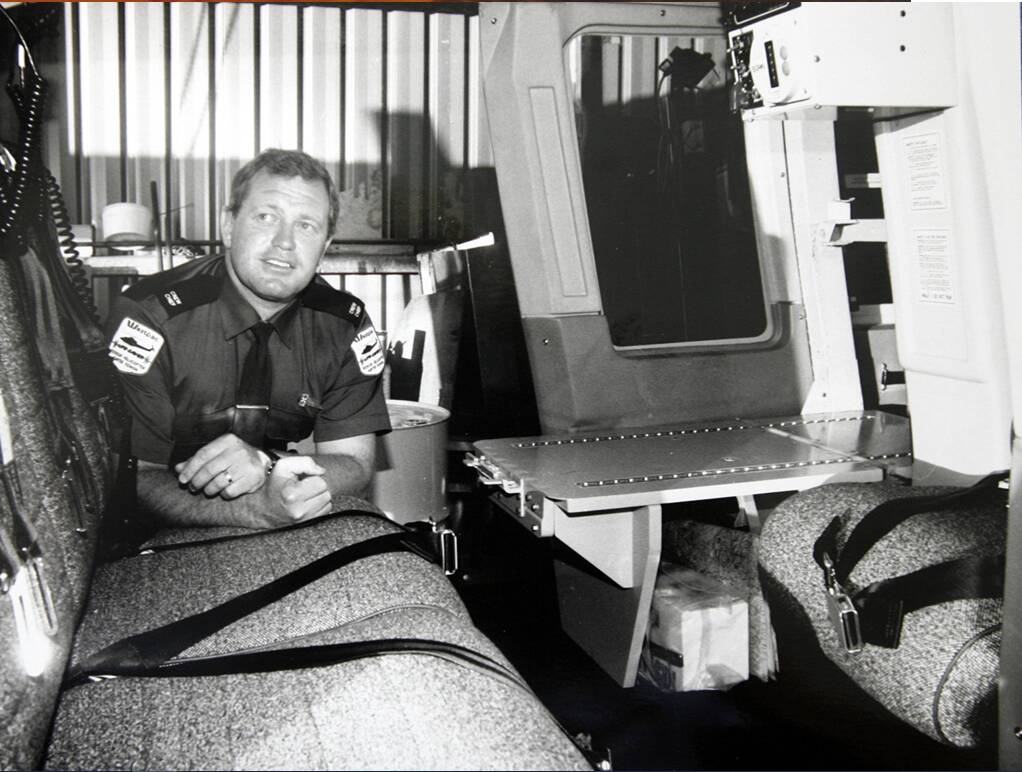

Nicko joined the service as a teenager when it was a surf rescue chopper going up and down the beach in 1981. He volunteered before going full time in 1989, spent 26 years as crew chief. He retires this week.

Cookie has retired after coming on board in 1989 where he spent about 17 years as chief pilot alongside Nicko.

Nicko called Rampo their "success story" after bringing him on board as an aircrew officer in 1998.

Everyone needs to work together, and the self-described "regular blokes" see themselves as a single link in a large chain.

'I think we're under attack'

Nicko reckons three big things have happened in his life. In October 1989, he married his beloved wife. Two months later, he was called to the Kempsey bus crash.

It was Australia's worst road disaster which sparked severe PTSD, but it would take Nicko decades to realise it. Five days later, while still numb from the trauma, he was en route to a cardiac arrest when he thought Newcastle had been bombed.

"The emergency service radios just started going off in the cockpit," he said.

"All you could hear was 'this has been hit, and this has been hit, and this is down, and this has collapsed, this is on fire, we've got people trapped here'."

All aircraft were grounded except the Westpac Rescue Helicopter. Nicko asked the pilot what was going on.

"He looked at me, and he was very serious, and he said 'mate, I think we're under attack'," Nicko said.

It was a devastating earthquake that razed parts of the city and killed more than a dozen people.

"We just didn't know what we were going to face," Nicko said.

"Newcastle had gone from this disaster that happened at Kempsey that I was involved with then five days later we had this earthquake, and Newcastle was basically on the bones of its arse.

"The whole rest of the country rallied and looked after us, it's amazing how people look after their own."

'Crazy 24 hours'

Rampo and Nicko weren't meant to be at work the day in 2007 that the bulk carrier Pasha Bulker beached at Nobbys in a storm that would go down in history and ultimately kill nine people.

"We thought it was a joke," Rampo said.

They took off in the chopper and were meant to be backed by a second, but it had to abort mission.

Rampo was winched down to the Pasha Bulker in a wetsuit 18 times to rescue the crew. One by one he managed to wrangle them into the chopper.

"I was getting zapped every time," Rampo said. "It was a shocking experience. We just kept going until there was no one left."

He said waves were crashing over the ship and the weather was so wild he could hardly see.

"I get seasick and the ship was still moving around a fair bit," he said. "It was quite a crazy 24 hours ... that's the biggest job I've ever been involved in."

Nicko said the storm was so violent he had trouble just staying in the aircraft.

The Westpac Helicopter Service was awarded for the crew's bravery that day.

Faced with life-or-death

Cookie said the most dangerous thing he's had to do as a pilot was fly blind at night.

He was instrumental in getting night vision goggles approved for Westpac Rescue Helicopter pilots almost 20 years ago.

"The most hazardous thing we used to do is go out at night and do black hole approaches," he said.

The chopper would go on a night mission, approach landing and wait for some ground illumination, so any object that appeared in the chopper's beam on the way down was an obstruction.

"You either got good at it, or you died," Cookie said.

Now, the helicopter doesn't take off without night vision goggles on board.

"It was just a huge relief," he said.

The helicopter has to stick to all the air rules, but Cookie said there was still a lot that can weigh on a pilot's mind.

"We all hate thinking there's a job that we could have done, because quite often, people's lives are at stake," he said.

Just a few weeks after practising a very rare and often deadly "drive shaft failure" during training overseas, it happened to Cookie in-flight.

He was able to safely land.

"We are so lucky we've got people like this who bring us home every day," Nicko said.

Coping with constant 'worst days'

The rescue helicopter team sees patients on the worst day of their lives. They've relied on their mateship and camaraderie to get by, but it can be overwhelming.

"I got severe PTSD, and I've never shied away from talking about it," Nicko said. "It got too much for me, I just couldn't do it."

It's why he left the service, realising decades later that the Kempsey bus crash triggered his PTSD.

Thirty-five people died and 41 others were injured in that crash.

The first call he made after the devastating fatal Greta bus crash in June was to the crew that were tasked to the scene.

Cookie said he tried to rationalise traumatic events.

"You didn't cause that mishap and you're trying to do your best to help them," he said.

Rampo admitted he'd "seen enough stuff now to last me a lifetime".

He said talking things over with his late wife, who was a nurse, and with the other staff and family, was important.

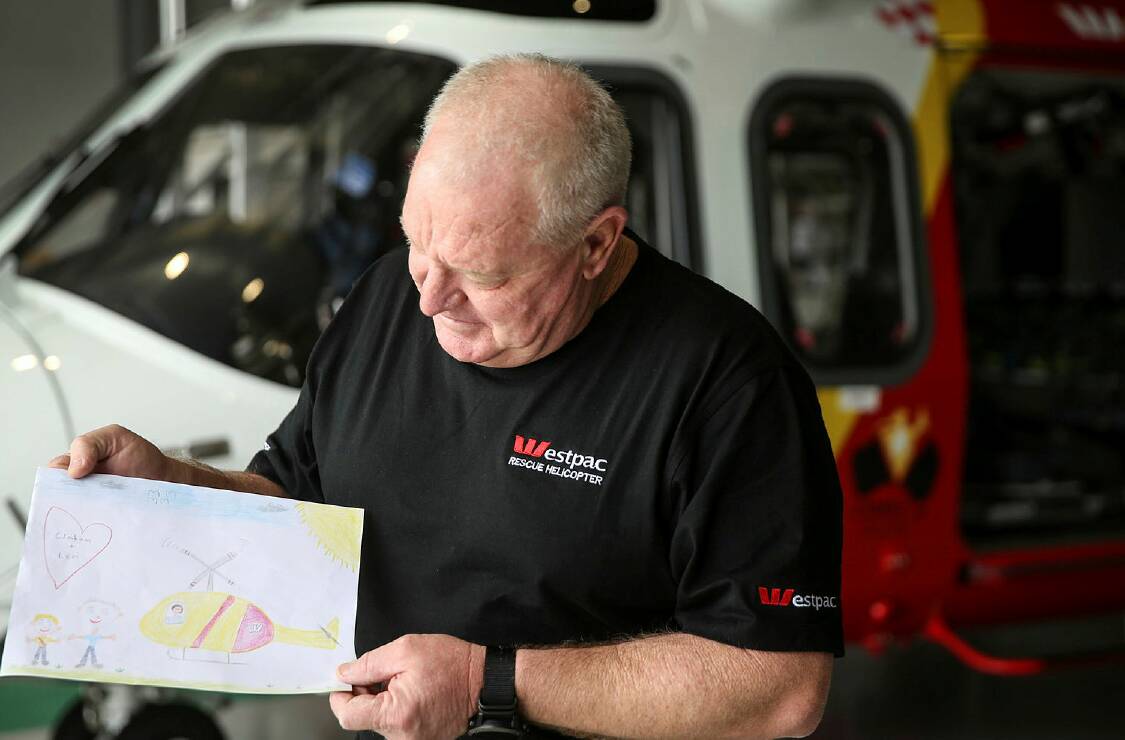

The patients that come back

There are three families Nicko has met through his work that he's still close with. At a golf day in Muswellbrook raising money for the Westpac helicopter years ago, a woman came up to him who's baby daughter wasn't breathing when she was born. She was now nearly 20 years old.

Nicko remembered her and the job.

"She said, 'well she's on her way down here to see you'," Nicko said.

"We cuddled and kissed and cried and all that sort of stuff and then we stayed in touch."

Her mother later asked Nicko to walk her daughter down the aisle at her wedding.

"I still get emotional," Nicko said, his voice cracking.

"She's got two beautiful daughters of her own now."

They don't hear from people all that often, and certainly don't chase them up.

"When they come back and say 'thank you' and you see them walk into the hangar after they've been told they're never going to walk again, well that's very good," Nicko said.

Humble heroes

Nicko, Cookie and Rampo see their role as a small link in a larger chain.

"We, as part of the flight crew, don't touch the patients," Nicko said. "I've never put a band-aid on anyone.

"Our job is to get them there and back as quickly and safely as possible."

Rampo agreed, and said the doctors and paramedics on board did amazing work in tough conditions.

"You see how our doctors and paramedics work on the side of the road and it just blows your mind," he said.

Everyone contributes, from the paramedics to the in-hospital care team and those who rehabilitate the patient afterwards.

Nicko said their job isn't more important just because they land in a helicopter.

"We're no different than the average bloke in the street," he said.

"We're just fortunate that we landed in a role we wanted to do, and had the gall to chase the dream."

It also doesn't protect them from getting into trouble or having to use the service themselves.

It's why they support it so passionately and are so thankful that the community backs it so fervently too.

"Just because we've got the word rescue on the side, doesn't mean we're not going to die, like anyone else in an aircraft accident," Nicko said.

"Just because we wear rescue on our sleeves doesn't mean we're immune to any disasters or traumatic things that happen.

"It's not just about us ... it's about praising the other people who keep this service going."

Into the future

When people ask Nicko if he'd do it again, he doesn't hesitate.

"Yeah I would, but I would change the way I did things," he said. "I've had over half my life here and I've met some beautiful people."

Nicko alone has done 7100 hours of flying time and manned 2639 winching operations.

"All I know is I'm never getting back in a helicopter again," he said.

Cookie compared working at the Westpac Rescue Helicopter Service to being part of a professional sports team.

"It wasn't a job, it was a lifestyle," he said.

They all said the support of their families and the community has been immeasurable, now they just want to see the service continue to thrive.

All three remember the days in the early 1980s when paramedics would have to get called in from hospitals to go on a chopper call-out, and the first bubble-style Bell 47s that carried the patient on the outside.

The twin engine helicopter marked a major step forward, as did the service's expansion into the north west with a base in Tamworth.

The Newcastle base was built on a "little triangle of land at Broadmeadow" and "six months later it was too bloody small", Cookie laughed.

Now the chopper is based in Belmont and more than 100 staff work there.

"To see these blokes come through and take the service to a new level, I sit back and I'm quite proud of that," Nicko said, gesturing at Rampo.

They've seen the service take off, and are excited to see where it goes next.