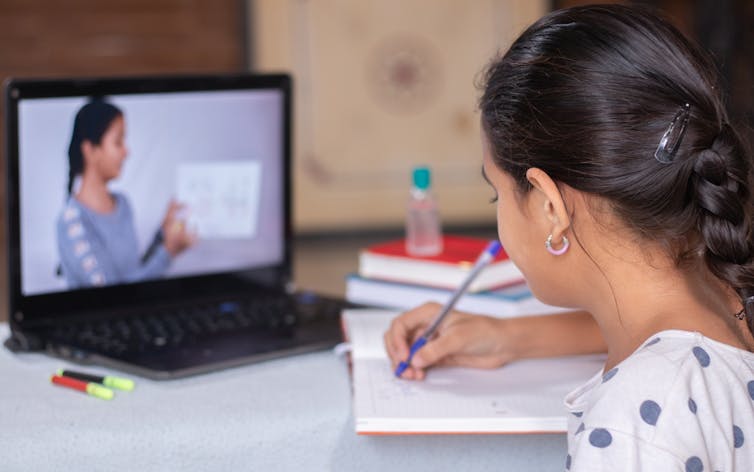

When COVID forced school closures, many parents found themselves more involved than ever with their children’s learning. For some parents, it was hard work but broadly achievable. Many migrant parents, however, found themselves at a distinct disadvantage.

Parental engagement is strongly linked to student learning outcomes.

With learn-from-home likely to return the next time there is a pandemic or other emergency, it’s important we understand why many migrant families found this mode of education delivery so incredibly challenging – and how the system can be improved.

We interviewed 20 migrant parents from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, and South Sudan who told us about the complex challenges they faced during lockdowns.

Language and technological barriers

Many of our interviewees told us limited English language proficiency made it hard to engage with their children’s learning. Understanding school and government messages was often a struggle. One parent said:

My daughter has a very native accent, and it is difficult for me to understand what she says […] Sometimes I do not understand what she wants or how I should help her. When I approached the school, they sent me English emails that I didn’t understand.

The pandemic also highlighted Australia’s digital divide; some participants struggled to set up their digital devices.

Limited parental digital literacy makes difficult to monitor student learning, especially in large families. Some parents told us they knew their kids only pretended they were on school tasks, while really watching YouTube or playing games.

Financial pressure and competing demands

Our interviewees also reported intense financial stress during lockdowns. As children stayed home for an extended period, grocery and utility bills soared. One parent told us:

You need to spend more. They eat more; they want to play in the bathtub. They watch TV; I have to use the vacuum cleaner and washing machine more often.

Parents had to also buy tablet devices and printers for children to participate in remote learning. Worrying their children were not doing schoolwork properly, some paid for tutoring and spent more on books.

Many parents worked full time during the pandemic and had limited time to educate their children. One participant reflected:

I have to work and be a teacher at the same time. It is not possible.

Another said:

I am a single mum with four kids from Year 1 to year 7. […] I have to deal with four different age groups, four schools, four classes, and four iPads. […] Sometimes, I need to cut my sleep hours, which again makes me wake up tired.

Uncertainty and withdrawal

Some parents eventually withdrew from their children’s education:

I have asked my children to do their duties on their own. […] In the case of my little son, I only know that he progresses through his course, can pass his units, and proceed to the next year, but I am not aware of his academic situation.

Reflecting on his inability to support his children’s learning during the lockdowns, one parent told us, “it’s out of my hands”.

Another told her child’s school:

Look, you need to provide me with simpler guidance. I’m not a teacher; provide me with a bit simpler communication; what they need to study, what they need to learn.

Read more: Learning from home is testing students' online search skills. Here are 3 ways to improve them

A sigh of relief

Almost all parents who participated in our study reported remote learning was exhausting.

One parent said:

You get tired of your children; you’re connected to them, that is good, but now it’s too much. I can’t wait until they get back to school.

Some parents worried about the potential strain of remote schooling on their relationships with their children.

One single mother, working full time while her child was home alone, told us:

I had to teach him while he was very impatient and expected me to know the answer for everything. When I was a little unsure about any subject, he got angry and miffed. So, I decided not to help him […] I told him: ‘Look, do whatever you can and leave the rest undone; when you get back to school, ask your teacher.’ I came to the conclusion that the bond and the relationships between a son and a mother are far more important than schooling and learning.

Others in the study also reiterated the importance of not putting too much pressure on already distressed children.

Emergency remote learning may return

Our research showed migrant parents faced myriad challenges during the remote learning period, with some only able to engage in a limited way with their children’s education.

Remote learning may very well return in future when the next disaster strikes, so it’s crucial we prepare for such disruption by improving equitable access to education delivered online and at home.

To achieve this, we must ensure:

all students have access to digital remote learning devices

disadvantaged families receive additional support (including financial and language support) during remote learning periods

all parents are well informed about their roles and responsibilities, and

school messages are easy to understand.

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of research team members Dr Hossein Shokouhi and Dr Ruth Arber.

Tebeje Molla works for Deakin University. He has received funding from the Australian Research Council, the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, and Deakin’s Faculty of Arts and Education. Tebeje has published on refugee education and is a member of the Refugee Education Special Interest Group (www.refugee-education.org). This story is part of The Conversation’s Breaking the Cycle series, which is about escaping cycles of disadvantage. It is supported by a philanthropic grant from the Paul Ramsay Foundation.

Amin Zaini works for Deakin University, School of Education where he obtained his PhD. Amin is a lecturer, a unit chair, and a Chief Investigator, at Deakin, and has already received an internal grant to work on migrant and refugee families. His areas of expertise and interest involve Education, social justice, as well as the analysis of power relations in the society.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.