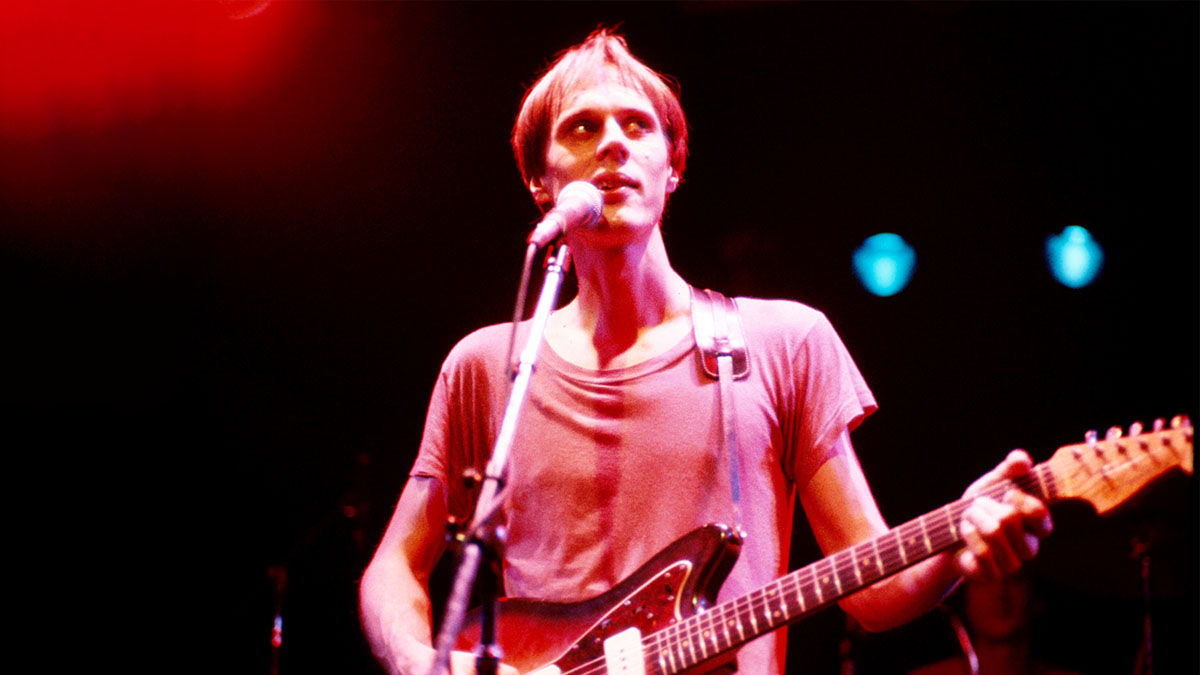

Tom Verlaine, who died on January 28, 2023, had an approach to playing guitar that was never easy to describe. Post-punk, art rock, art punk, whatever; it was one of Verlaine’s great creative achievements that over three studio albums with Television, and a prolific solo career, he was able to unshackle his style from labels. Hard to define, sure, but you know it when you hear it.

The sound he pioneered in Television, along with second guitarist Richard Lloyd, had a propulsive yet cerebral power, grandiose yet melancholy, intense yet epic. Based in New York City, where they regularly performed at legendary club CBGBs, Television had an energy and attitude which suggested punk. What came out the speakers, however, would challenge that conclusion. There was nothing quite like it.

Maybe this is what happens when you approach the guitar from a different perspective. The instrument was not Verlaine’s first love. When he was a kid growing up in Delaware, he started out on piano before picking up the saxophone as a young teenager. He liked symphonies. He liked jazz. Speaking to Guitar Player in 1993, Verlaine confessed that he hated guitar music for years.

“I played piano because when I was a kid I’d be really transported by symphonies,” he said. “My mother would get these supermarket records of overtures. That was music for me. The only thing I liked on radio were flying saucer songs. In the early 60s I hated pop. An older friend of mine had some Coltrane and Ornette Coleman records, and that’s the music I liked. I had a brother who bought Motown, and I thought it was totally twee. The first rock record I liked was Yardbirds stuff, because it was really wild.”

The Kinks and The Rolling Stones can also claim credit for changing Verlaine’s mind about guitar, and doing as they would do many times before and since, changing music history over the course of two frenetic rock songs. All Day (And All Of The Night) and 19th Nervous Breakdown did the damage.

“Those are the records that made me think the guitar could be as good as jazz,” Verlaine told Guitar World in 1981. “Up until then the electric guitar was a stupid instrument to me. When I heard the solos on those records, the sound, the general sound, that’s when it occurred to me that the guitar was a cool instrument.”

Having no intrinsic affection for the guitar, Verlaine could easily resist the impulse to covet other players’ styles. It is often thus: the best guitar heroes are the ones who never wanted such status. Fortune favours those bold enough to experiment with an instrument. It also favours those who work at it.

Television were famously dedicated to rehearsals. Their marathon practice sessions would be masochistic if just in service to a sound wrought on three powerchords and a 4/4 backbeat. Verlaine and Lloyd had designs on Television being something more. Besides, the Ramones would soon claim brevity for their own. Expansiveness was the smart play.

Set loose and turned wild in the febrile thrum of 1970s New York – the milieu of Blondie, Talking Heads et al – Verlaine’s electric imagination reconfigured guitar music and set the table for a generation of alternative rock acts, many of whom would stake their own claim to greatness.

Television’s debut album Marquee Moon, with its iconic cover photo by the great Robert Mapplethorpe, remains essential, remains exhilarating, and remains somehow special and alien even though the independent rock cognoscenti has kept it on regular rotation since its hit record stores in ’77. It is one of the most influential rock albums of all time. The likes of Sonic Youth, Pavement and Johnny Marr were listening.

“It was more expansive,” said Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, speaking to ShortList in 2020. “The guitar interplay between Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine was just really informative for me. It was really dry and super-poetic whilst still being really unpretentious.”

What Television were doing was something new. Just as it worked with Sonic Youth, who came out of a similar cultural environment, weaned on experimental music and art, it did in England. In a 2021 Guitar World interview, Johnny Marr said Verlaine and Lloyd were the fresh blood guitar music needed.

A lot of us took note from Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine. Those guys were game-changers. I loved all that... and still do

Johnny Marr

“This was at a time when there were a lot of things being done on guitar that I felt were outdated and corny,” Marr said. “But there was also a generation of young men in the UK and America who were onto something new – Robert Smith, John McKay, Will Sergeant. A lot of us took note from Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine. Those guys were game-changers. I loved all that... and still do.”

The long approach towards the release of Marquee Moon is the history of a band taking the time to evolve before announcing themselves on wax. Formed in 1973 with Verlaine’s old school pal and countercultural Zelig Richard Hell on bass, Billy Ficca on drums and Lloyd on guitar, Television would soon mix things up, swapping out Hell for Fred Smith, then of Blondie.

There was a certain amount of ruthlessness in that. When Hell and Verlaine moved to New York, Hell got Verlaine a job at the Strand bookstore. But perfectionism was in Verlaine’s blood. It was part of the internal logic of the band.

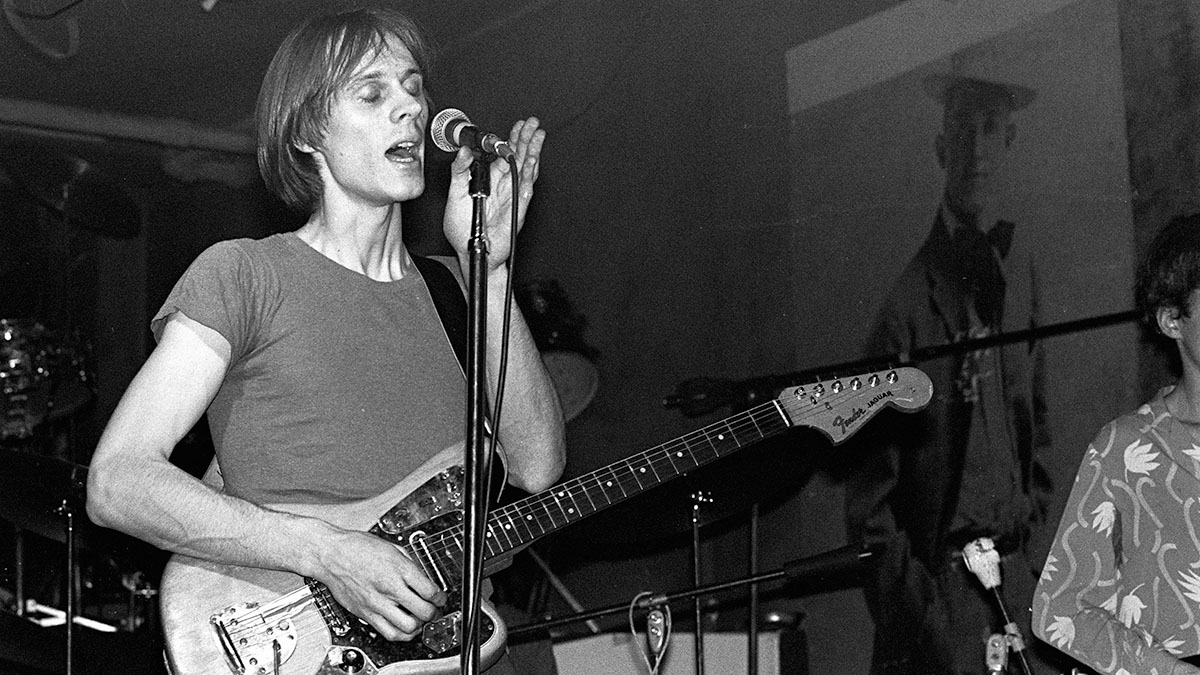

No-one was safe. Brian Eno was brought in to produce the Marquee Moon demos and Verlaine was unsparing in his judgement, saying it all sounded like the Ventures, lacking juice. The sounds Television were chasing were a reaction to the rock guitar consensus at the time that favoured Marshall stacks and humbucking pickups. All of that was out. Theirs would be a Fender sound.

The angular cut of a single-coil pickup was their thing. The price of the Fender Jazzmaster at the time was also appealing. Verlaine found a ’59 Jazzmaster with a bronze pickguard and that made it on their debut. Sonic Youth would explicitly follow Verlaine’s lead a few years later to seek out Fender offsets as the affordable option.

Rare and oddball guitars were always welcome. Verlaine also used a Gretsch G6123 Monkees signature model that he picked up for $80, a guitar that was only on the market for a couple of years at the height of The Monkees’ popularity. There were Danelectro and Vox guitars, and a see-through Ampeg Dan Armstrong Plexi, presumably for the same reason that everyone else played one; because it looked damn cool. There were Strats and Jaguars, too, and an Epiphone Al Caiola.

In later years, Verlaine would use a modded Strat that was fitted with three lipstick-style pickups and a neck taken from a Jazzmaster. Guitar amps were mostly from Fender, too, with the high-powered Super Deluxe tube combos a cornerstone of their sound. Vox AC30s, Music Man HD-130 4X10 combos and a Dumble Overdrive Special found themselves on Verlaine’s backline over the years. Television’s tech, Robert Darby, built them a Valvotronics amp. Like many players of the era, Echoplex tape echoes were used, even if just for the preamp’s secret sauce.

Like most serious Jazzmaster players, Verlaine’s models were upgraded with Mastery bridges. He also favoured heavy strings, 0.014s or 0.015s for the high E, a 0.054 for the low E, and always a wound G. Technique-wise, he would use a pick but play close to the neck pickup.

Marquee Moon was quite the debut, but there was more where that came from. Adventure followed in 1978, deepening Lloyd and Verlaine’s understanding of one another’s styles. The energy was different, the songs every bit as strong. Besides, what would it have served Television to have tried to chase the same thrills? If Marquee Moon was some after-hours adventure in the city, a transcendent fever of neon, Adventure is the morning after.

Whether it is on the loose, sun-fried groove of Glory, the mid-tempo strut of Foxhole, or Verlaine favourite The Dream’s Dream – mostly instrumental bar one verse, it sails off into the ether, closing the album out, the cool precision of Lloyd and Verlaine’s phrasing present and correct.

The treble gives it a wiry clarity that again speaks to the perfectionism; a Super Deluxe is the sort of amplifier that punishes sloppiness. For better or worse, if you play a note on it, you hear it loud. There is no hiding place. Speaking to Hit Parader in 1978, Verlaine admitted that theirs was a difficult sound to capture in the studio.

“It’s a bright kind of sound,” he said. “It’s not fuzzed up, it’s not like say, a Bad Company sound where you plug a Les Paul into a Marshall – which is the formula for about 80 per cent of rock ’n’ roll. We’ve got a number of weird little guitars which we use with weird Fender amps, and it produces a very different kind of sound. A lot of engineers don’t know how to translate it so it will work on a record.”

Television would break up just months after the release of Adventure. Verlaine endured a year of contract wrangles with Elektra as he gathered material for his self-titled solo debut. Stylistically, the apple did not fall far from the tree. Sure, Lloyd no longer offered Verlaine a foil, but the licks, voice and songwriting mounted a convincing case that the best was yet to come.

David Bowie thought so, and recorded a cover of the song Kingdom Come on his 1980 album Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). Although Verlaine was scheduled to play on Bowie’s version, it was Robert Fripp who played lead instead. Apparently Verlaine’s search for the perfect tone, auditioning amps ad nauseam, was not everyone’s idea of fun.

Even when I listen to stuff that Tom and I do, sometimes I have to pull myself out of it to determine who’s where, who’s what

Richard Lloyd

But it worked for him. The tones he found on Dreamtime (1981) scratched and shimmered around his vocal. Postcard From Waterloo, from 1982’s Words From the Front, is reference quality surf-rock tone, a splash of vintage Americana that would be reprised in 1992 for the instrumental album Warm and Cool – a record found him experimenting with fingerstyle.

Television would reform in 1992, releasing a self-titled album, touring, and then staying officially active until Verlaine’s death. Later, Verlaine would guest on records by the Violent Femmes, James Iha and Patti Smith. He would score silent movies for the Douris Corporation with Jimmy Ripp, half composed, half improvised.

Few understood Verlaine better as a guitar player than Richard Lloyd...

“It’s like we become one guitar,” said Lloyd, speaking to Guitar Player. “I can tell the difference between our parts and our styles when we’re playing leads, but even when I listen to stuff that Tom and I do, sometimes I have to pull myself out of it to determine who’s where, who’s what.

“I don’t think there’s another band that has that with two guitars, where one doesn’t strum and one doesn’t play lead all the time, and they don’t switch or play leads at the same time in 3rds – we’re not the Allman Brothers, and we’re not Status Quo, we’re not heavy metal, and we’re not a strum band. The parts are very well defined in their interconnectedness. They really make one piece, and I don’t know exactly how that happens.”

If such magic could be explained, it wouldn’t be magic anymore. We should still try. Verlaine’s guitar parts are vines to be scaled to see how it looks and sounds from on high, another perspective on the instrument. Verlaine’s guitar was pitched at the avant garde but was nonetheless relatable. Like Robby Krieger of the Doors, he mixed alien styles, different modes, a jazz sensibility painting with Mixolydian and blues. If there is a lesson to be taken, it is to never be satisfied.

“When I do hear a guitar in contemporary music, it always has the same sound,” Verlaine once complained. “I guess it’s a distortion plugin – ‘Preset 80’ or something. Who cares?”