Michele Alboreto was not someone who became interested in racing only once he was involved. He was like you or I – a pure fan – long before he became a driver, and each year he’d make the 45min journey from home in Milan to Monza for the Italian Grand Prix.

In 1970, he was left tearful on witnessing Jochen Rindt’s fatal accident in practice, then felt the exhilaration 24 hours later as Clay Regazzoni, in only his fifth Grand Prix, won the race for Ferrari. In one weekend, 13-year-old Michele had experienced motor racing in extremis.

Perhaps in honor of Rindt, he became a fan of Lotus and in particular, Ronnie Peterson. Each year, Albo would bravely stand among the die-hard Ferrari-or-nothing tifosi but waving a Lotus flag for his hero. As soon as he started racing for Scuderia Salvati in Formula Monza in 1976 this young Italian lad adopted Peterson’s Swedish helmet colors, blue with a yellow peak. It would remain that way to the end.

Salvati, impressed with its new charge, moved him into Formula Abarth for 1978, and steady improvement in technique and understanding of racecars in general culminated in victory at Magione and fourth in the championship. That was enough to land Alboreto a drive in the final Italian Formula 3 championship round of the year – again at Magione – and on his debut he finished fourth.

Joining Giampaolo Pavanello’s Euroracing team for ’79, Alboreto raced in both the European and Italian championships. In the national series, it was a successful year, and he finished second overall, having triumphed at Magione, Misano and Imola. Inevitably the competition was tougher on the European stage, where he finished sixth, his highlights being poles at Magny-Cours and Monza, runner-up finishes at Zolder and Enna, a third place at Monza, and five fastest laps.

Rather than rush up the ladder series, 22-year-old Alboreto stayed on in F3 for ’79 and put his experience to good use, beating future F1 winner Thierry Boutsen’s Martini-Toyota to the European crown, while also grabbing third in the Italian Series. No less impressive was a one-off trip to Silverstone for a foray into the British Formula 3 scene. After qualifying 10th from 35 entrants, Alboreto raced his way up to fourth in the first heat, finished third in the second heat and took third overall – the lone Alfa-powered machine in a Toyota-dominated Top 10.

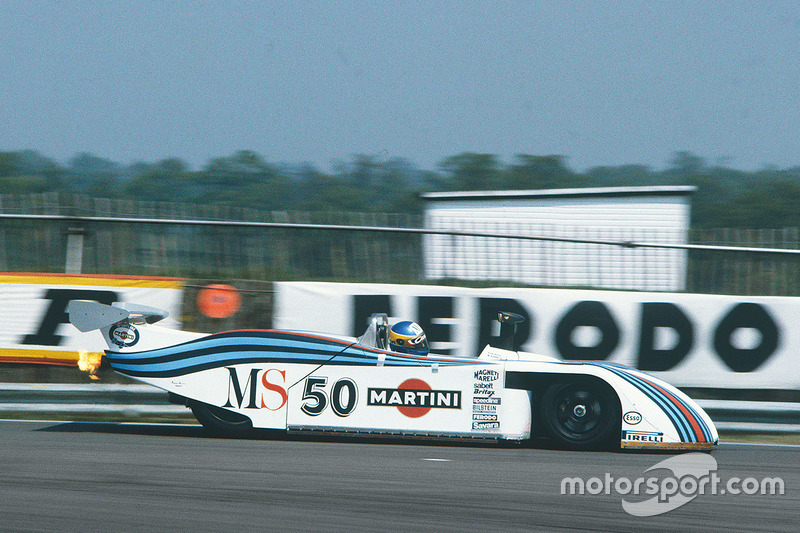

While F3 of course took priority when pursuing an open-wheel career, Alboreto was one of several young drivers who at this time raced for the Lancia Corse sportscar team in the World Championship for Makes, forerunner to today’s World Endurance Championship. Driving a Group 5 Beta Montecarlo Turbo, he started four races that year, two partnering future F1 rival Eddie Cheever, and two alongside rally legend Walter Rohrl. Alboreto’s three second places and a fourth helped Lancia very narrowly edge Porsche for the title.

Disappointed at being unable to land a works drive with March or Ralt for Formula 2 in 1981, ‘Albo’ joined Minardi in Formula 2, despite the team’s 281 chassis being off the pace. However, after four races he got word that Ken Tyrrell needed a new partner for Cheever in Formula 1, since incumbent Ricardo Zunino had been 1.7 and 2.4sec off the American’s pace in his two outings in the admittedly outmoded Tyrrell 010 Cosworth. ‘Uncle Ken’, also lacking a major sponsor, signed up Albo for the San Marino Grand Prix, the wheels to the deal having been oiled by funds from Count Zanon (one of Peterson’s former supporters who had become a friend of Alboreto), and sponsorship from Imola Ceramica, a local tiling company.

The new kid made an immediate impression by outqualifying the more experienced Cheever, although this would happen only one more time in the year-old Maurice Philippe-designed 010 as the rookie struggled initially to adapt to the numb ground-effect chassis. It wasn’t until the replacement 011 arrived mid-season that Alboreto showed more faith in finding the car’s limit and crept closer to Cheever’s pace – despite running Avon tires compared with his teammate’s Goodyears.

Alboreto’s simultaneous F2 campaign was fraught, the Minardi rarely capable of threatening the works teams, yet he earned pole in Pau, and later won in Misano, but necessarily skipped a couple of rounds to fulfill his F1 commitments. Arguably the high points of his season came in sportscars, finishing second in the Group 5 class in the 24 Hours of Le Mans after sharing a Beta Montecarlo with Cheever and touring car ace Carlo Facetti, and then winning the Watkins Glen 6 Hours outright with Riccardo Patrese.

Rival Formula 1 teams made offers to Alboreto for 1982, but the pragmatic 25-year-old elected instead to sign with Tyrrell for two more years and continue his Grand Prix education.

“For me, driving for Tyrrell was the best thing at that stage in my career,” he explained to Maurice Hamilton in an Autosport interview. “Absolutely fantastic. Ken taught me so much and yet never put me under pressure. I started learning the day I arrived and I was still learning the day I left. It was just the right experience for a driver starting in Formula 1.”

Elevated to team leader status for 1982, and with his 011 now running Goodyears, Albo scored two fourths in the opening three races of the season and, in the race boycotted by most FOCA teams at San Marino, he joined Ferrari drivers Didier Pironi and Gilles Villeneuve on the podium. At Zolder, the Ferrari entries were withdrawn following Villeneuve’s tragic death in qualifying, and Alboreto lined up fifth on the grid, but his usually reliable Cosworth engine let go on race day.

The normally aspirated teams were facing an uphill battle; compared with the turbo cars of Ferrari and Renault and soon Brabham-BMW, they were giving away some 300hp in qualifying and 150 on race day. Yet Alboreto, like eventual champion Keke Rosberg (Williams) and the McLaren drivers (Niki Lauda and John Watson) was at the forefront of the Cosworth battle. In fact, Alboreto’s next batch of points would come on what were very much ‘power tracks’ – sixth at the original Paul Ricard with its mile-long Mistral Straight, fourth at the original Hockenheim and fifth at Monza. His reputation was burgeoning. Come the finale at Caesars Palace, Las Vegas, Albo was outqualified only by the Renaults, and when one blew up (Rene Arnoux) and the other developed a bad tire vibration (Alain Prost), the Tyrrell driver was there to pounce with 24 laps to go, and land his first victory – and Ken’s first in more than four years.

Alboreto had continued to put his name up in lights in what was now called the World Endurance Championship, as Lancia moved up to Group 6 with its svelte barchetta, the LC1. Whenever his car finished, he would triumph – with Patrese again in the Silverstone 1000km, with both Riccardo and Teo Fabi in the Nurburgring 1000km, and with Piercarlo Ghinzani in the Fuji 6 Hours. However, these would remain his last sportscar wins for well over a decade, as in ’83 Lancia produced a Group C car, the LC2, and it was blown aside by the Porsche 956s. And anyway, for the next 10 years, Albo needed to focus on F1.

If the Cosworths had been struggling in ’82, things became even tougher the following season. The best normally aspirated cars were 4-5sec off pole at tracks such as Paul Ricard, and since the turbo-powered cars were becoming more reliable, so there were fewer opportunities for a ‘Cossie’ to swoop in for wins. The last to do so with the Cosworth DFV were Watson at Long Beach and Rosberg at Monaco, while Alboreto ran the development DFY unit from Monaco onwards and scooped a fortunate win at Detroit when Nelson Piquet’s Brabham picked up a puncture. Ford would not win again in F1 for six years, while Tyrrell would never win again.

Following Alboreto’s Vegas triumph the previous year, Enzo Ferrari had publicly commented: “I have said, and I confirm it, that the day Alboreto becomes available, I will be happy to put a car at his disposal.” In the mean time, for 1983 Il Commendatore had retained Villeneuve’s replacement, Patrick Tambay, and signed Arnoux from Renault, following Pironi’s F1 career-ending shunt at Hockenheim. Both Tambay and Arnoux performed well through the 1983 season and between them kept the Harvey Postlethwaite-penned Ferrari 126C2Bs and 126C3s prominent, so it seemed curious that Ferrari was willing to break up this team. Yet that is precisely what happened. Alboreto, made aware that Tyrrell had no turbo engine manufacturer lined up for the following year, put himself on the market and signed with Ferrari in July. A couple of months later he and others learned that the deal was at the expense of his friend Tambay.

Ken Tyrrell would miss his Italian ace, as he told Autosport a couple of years later.

“The thing about Michele was that he related so well to what was, for him, a foreign team,” said Ken, who had watched his team dominate in the Jackie Stewart era and then become occasional winners with Jody Scheckter, Patrick Depailler and Alboreto. “He has no airs or graces. If he says he will be somewhere at 3 o’clock, he will be there at 3 o’clock. He is a gentleman – and he’s bloody quick in a racing car!”

Race engineer Brian Lisles, later of Newman/Haas Racing Indy car team fame, observed: “[Alboreto] is one of the few drivers around who purposely adopts a completely different style for qualifying; he really put our car through its paces for that one lap. He would say that this was when he used ‘the extra half-second I carry in my pocket.’ He would come in, grinning from ear to ear, and the poor old car would sit there, breathlessly tinging and pinging as it cooled down. He really liked that. So did we.”

So too did Ferrari but there’s no doubt Alboreto expected more from the relationship when he signed up. Despite the trauma of its 1982 season, Enzo’s squad had won the Constructors’ Championship that year, and then retained it in ’83. The omens were good. And yet Michele would discover the following year’s 126C4 was rarely a match for John Barnard’s new TAG Porsche-engined McLaren MP4/2 piloted by Alain Prost and Niki Lauda.

In more recent times, Ferrari’s combination of Jean Todt, Ross Brawn and Michael Schumacher would become a prime example of how, by operating with a ‘one for all and all for one’ integrity and a desire for continuity, a Formula 1 team comprising prime talents can dominate. And that period in the Scuderia’s history may cause one to forget how very differently it had been run in previous eras. Pre-Todt, Ferrari was infamous for damaging polemics, leaks to the media and various internal factions pulling in several different directions, each competing to have the ear of the Old Man at Maranello. Power struggles, personal agendas and sometimes sheer spite had been as much a part of the fabric of this great institution as scarlet cars, prancing horse logos and trophies.

Such impediments to progress resulted in squandered opportunities and were something that the direct and stubborn John Surtees and direct and wily Lauda had both tried to resolve, if only fleetingly. Another Ferrari legend, Villeneuve, had somehow risen above the morass of politics and was adored, but this can be done only if you’re both supernaturally quick and willing not to meddle too much on the technical side. Maybe Alboreto thought that he too could stay immune to the watch-your-back atmosphere that pervaded the corridors of power at Maranello because, despite being a student of racing heritage, his move to Ferrari was borne not of passion for the marque but of pragmatism.

“I don’t feel this famous mythology about the Ferrari team,” he told journalist Mike Doodson. “It is just a very good team with a lot of history behind it. I like Mr. Ferrari because he is such a strong man. I want to be able to grow old like him and to be like that myself… But I don’t feel the mythology when I a driving: I don’t see the color of the car or the little horse on my steering wheel. I just see the two front wheels and my hands on the steering, and I try to go as quick as possible.”

That was quick enough to put him on the front row for the 1984 season-opener in Brazil, but a loose bolt in a brake caliper allowed the fluid to drain away and he was forced to retire when the system overheated. At the next round in Kyalami, the Ferraris were well off the pace. But in Belgium, Alboreto and Arnoux locked out the front row, and Michele led from start to finish, while Arnoux took third. Thereafter, however, the team was overwhelmed by not only McLaren’s red-n-whitewash, but also reliability issues for Alboreto and distinctly up-and-down performances from Arnoux. The pair would finish in very distant fourth and sixth places respectively in the drivers’ championship, while Ferrari’s second place in the Constructors’ points table saw them finish with fewer than half of McLaren’s tally.

“After Belgium, we seemed to be on the right path,” recalled Alboreto, “but we made a wrong turning and it was downhill after that… The car was not good and there were problems within the team…Was it me? Was it the car?… I think the middle of the season was the worst time. The pressure to do well was incredible… I had to close my mind to everything outside and just get on with the driving – think of nothing else but the driving.”

Endless testing at Fiorano and constant changes of setups on Grand Prix weekends appeared to help the team rally, so that Albo scored a couple of runner-up finishes toward the end of the year, but still in qualifying the Ferraris were light years behind their principal rivals. Legendary engineer Mauro Forghieri was a primary casualty in this period, but the relationship between the drivers was not. Arnoux, an 18-time polesitter, was recognized as one of the very quickest drivers in Formula 1 in the early ’80s, so might reasonably have been upset when his latest teammate outpaced him most weekends. Yet Rene insisted that was never an issue.

"Michele was a fantastic guy,” he told me, “and the atmosphere between myself, Michele and Enzo was very good. It was not a good year for Ferrari but we all worked hard as a team. Whenever he was quicker than me, it was not a problem. And when he got good results, I would say, 'Congratulations, I am very happy for you'. It's very easy for there to be war between teammates, but with Michele and me it was impossible! He was a perfect man. It was the best relationship I ever had with a team partner.”

The pair remained together into ’85 – but only for one race. For reasons never explained, Arnoux was abruptly let go after just a single race – although qualifying 1.8sec behind his polesitting teammate, and being lapped twice on race day hardly helped his cause. Alboreto was left reasonably content with a runner-up finish on that occasion and was confident that the imperious McLaren team, which had switched from Michelin to Goodyear tires during the offseason, was now a bit more beatable with his new 156/85.

At a soaking Estoril, the #27 Ferrari was the only car left unlapped by the brilliantly-driven Lotus of Ayrton Senna. At Imola, Alboreto retired but set fastest lap. Then, on May 19 at Monaco, came arguably his greatest performance. Having qualified third, behind Senna and the Williams-Honda of Mansell, Albo pulled a stunning fishtailing pass on the Briton under braking for Ste Devote at the start of the fourth lap, and was hounding the Lotus for the lead on lap 13 when its Renault engine blew. Alboreto then pulled away from his opponents but, as leader, was the first to discover a major oil slick at Ste Devote five laps later. He shot up an escape road, kept the engine alive and turned around to rejoin the track, but saw Prost slip past into P1. Yet on lap 23, Michele caught and re-passed the Frenchman, and again appeared to have the race in his pocket. Then fate intervened once more: a punctured left-rear tire forced him to slither to the pits, and dropped him to fourth.

The Ferrari rocketed back out and Alboreto began a series of mesmerizing, qualifying-style laps, grazing the Armco barriers. Past Andrea de Cesaris' Ligier into third. Past the other Lotus of Elio de Angelis for second. Only Prost to go... Sadly, he ran out of time. Despite recording a fastest lap more than 1sec quicker than even his best rivals, despite pulling off more moves than anyone else on a track where it’s supposedly impossible to pass, Alboreto had to be satisfied as a gutsy and exhilarated runner-up.

In Canada a month later, he led new teammate Stefan Johansson to a Ferrari 1-2, finished third behind Rosberg and Johansson at Detroit, and then suffered a turbo failure at the French GP. Far more perturbing than this retirement, though, were the British Grand Prix, when he finished runner-up but was lapped by winner Prost, and Austrian GP, when again he finished on the podium but in qualifying had found himself two seconds slower than the Frenchman’s McLaren.

“We tried to respond and went the wrong way,” said Alboreto summing up this period. “We make everything in our factory – engine, chassis, gearbox, all of the car – [so] to put together a competitive package is very difficult. When you have problems and you don’t know exactly what is wrong, there is a panic, a grande casino, as we say in Italian. With Ken it was different. He never had enough money to have a grande casino…”

In between the British and Austrian rounds, Alboreto won in Germany at the new Nurburgring. An overambitious passing attempt at Turn 1, Lap 1, saw him collide with Johansson, puncturing one of the Swede’s rear tires – Stefan was stoical, Michele apologetic – and after Senna’s engine cried enough, Alboreto eventually performed an elbows-out pass on Rosberg and clinched victory. He now led the championship by five points from Prost. But sadly for him, that race had been the anomaly, Silverstone and Osterreichring were the trend, and Ferrari's fortunes plummeted thereafter. Albo failed to finish the last five races of the year, so as championship runner-up, his points tally was undeservedly distant from that of champion Prost.

As Johansson recalled: “I think Ferrari had changed turbos earlier in the season, and the engine just got worse and worse. We had one of the quickest cars at the start of the year, the other teams caught up, we tried to find more power, and then the reliability went. By the end of the season we had neither."

Aside from the reliability issues, Alboreto felt Ferrari’s testing policy was fundamentally flawed. He told Doodson: “I think Fiorano is not always an advantage for Ferrari. Sometimes it is the opposite, because Fiorano is too slow for these Formula 1 cars… It has slow hairpin-type corners. In fact we always find that our car is really good at Monte Carlo, but unfortunately there is only one race there each year! It is in the high-speed tracks like Silverstone, Zeltweg [Osterreichring] and Zandvoort where we have our problems.”

On the back of that disastrous end to 1985, the drivers were dismayed to discover the prospects for '86 were worse. As Johansson remembered, “When we were first shown the F186, Michele and I looked at each other and said, ‘Fuck! This is going to be a long season'."

The drivers’ misgivings over the scarlet humpback whale, one of the few bad creations by the talented Dr. Harvey Postlethwaite, were borne out: it never came close to winning a race. And in these circumstances, Stefan, although still slower than Michele in qualifying, frequently raced harder for longer. Ferrari’s backroom politics were finally dissolving the resolve of the Italian, and the fact that he was a Postlethwaite apostle would soon also put him out of step with Ferrari management. The good doctor, having created something of a dud, was being edged out in favor of newly signed ex-McLaren genius John Barnard.

Before the 1987 season started, Alboreto, alarmed at being unable to find common ground with the new technical director – he would later describe the trenchantly UK-based Barnard as “like a doctor trying to operate by telephone” – started speaking with Frank Williams about a possible move to the British squad for ’88. Williams, who had refused to be brow-beaten by Honda into replacing Mansell with Satoru Nakajima (!), was aware that the Japanese company would therefore likely respond by terminating its contract with the team one year early and placing Nelson Piquet elsewhere. However, until Williams got word that the two-time – soon to be three-time – World Champion was definitely heading for the exit, he couldn’t confirm there was a vacancy.

Michele understood and so re-signed for another year with Ferrari in ’88… not long before Honda confirmed that yes, it would be switching its engine supplies from Williams and Lotus to McLaren and Lotus the following year – and yes it would be placing Piquet in the latter team. With Alboreto off the market, Frank signed Patrese to partner Mansell for a desultory year driving the Judd V8-powered FW12s.

For that one season, you could regard these enforced circumstances had played out in Michele’s favor. At least, in this final (for now) year of F1 regulations allowing forced induction, he had a turbocharged car and could collect a bunch of podium finishes behind the all-conquering McLarens. But by then his morale was shot. When the brave, cocky and quick Gerhard Berger had first arrived to replace McLaren-bound Johansson for '87, Michele had risen to the challenge and the pair were evenly matched in qualifying and in race pace. However, not long into the second half of the year, the Berger-Barnard axis gained preeminence and Alboreto’s outright speed started slipping.

Through most of ’88 he looked a shadow of his former self, a man clearly serving out his time in a car desperately limited by its inability to match the McLaren-Honda MP4/4’s fuel efficiency. Albo summed up his disillusionment with both car and team at the Portuguese Grand Prix: as his F187/88 coasted down the pit straight to the checkered flag in Estoril, its fuel tank dry, two cars passed him and he dropped from third to fifth place. On emerging from the cockpit, a fuming Michele snarled, “Pah! At Ferrari, even the fuel gauges lie.”

His anger on this occasion was doubtless exacerbated by the fact that he was in no-man’s land regarding his immediate future. The idea of joining Williams had resurfaced one year on when he learned Mansell was heading in the other direction to replace him at Ferrari, and now Frank’s squad was a far more enticing prospect for he had inked a deal with Renault, the French manufacturer returning to Formula 1 for the start of the new normally-aspirated regs. Albo was sure he had a deal in place with the UK team, but just before the Italian GP, learned this was not so. Williams and engineering director Patrick Head didn’t like to hire two new drivers at once, and with Thierry Boutsen’s imminent arrival as Mansell’s replacement, they had elected to retain Patrese.

One man who'd never lost faith in Alboreto was Ken Tyrrell, and briefly their 1989 reunification worked. The Tyrrell 018, designed by Postlethwaite and Jean-Claude Migeot, was a sharp tool that made the most of the Cosworth DFR V8 unit which couldn’t match the huge-budget V10s of Honda and Renault and V12 of Ferrari. Alboreto’s fifth place in Monaco and a remarkable third place in Mexico both suggested the team was in the ascendancy and proved that a motivated Michele was still a potent force. However, a dispute over clashing cigarette sponsors – Tyrrell landed a Camel deal, Michele was a long-time Marlboro man – ended the relationship midseason. That couldn’t have been the entire story, however, because Albo saw out the remainder of the season in the Camel-backed Larrousse team! Once again he let his head drop, regularly outperformed by a teammate as flaky as Philippe Alliot.

Yet the switch to Arrows for 1990 saw Alboreto’s enthusiasm revived, despite piloting a car – the A11B update of a one-year-old design – that now, even on its good days was an also-ran, on its worst days a non-qualifier. Alboreto proved a match for young gun teammate Alex Caffi and believed better times lay right ahead: team owner Jackie Oliver had done a deal with Porsche for a V12 in 1991.

The new unit was a disaster. So unexpectedly bulky was it that the team, now branded for its title sponsor Footwork, had to start the year with the Porker shoehorned into an A11C, while designer Alan Jenkins hastily revised the dimensions of his ‘definitive’ 1991 car, the FA12. If that car was any better, the gutless 3.5-liter V12 anchor in the back prevented anyone knowing. By Round 7, the humiliated Porsche brand had gone and the team reverted to the trusty Cosworth. Even so, the season was an alphabet soup of DNFs, DNQs and DNPQs (Did Not Pre-Qualify in an era of 30-plus entrants for F1 races). Alboreto, Caffi and – while the younger Italian recovered from a huge shunt at Monaco – Stefan Johansson never had a hope of scoring points.

But Albo kept pushing, kept himself sharp, so he was primed to bounce back when Oliver signed a deal to use Mugen-run previous-generation Honda V10s for 1992. While these were neither on the cutting-edge nor light, they were reasonably powerful, exceptionally reliable and fitted well into Alan Jenkins’ simple and dependable new FA13. Michele posted just two retirements, blew new teammate Aguri Suzuki into the weeds and, had the current F1 point system been in place, would have scored 12 times in the 16-race season! However, back then, points were only distributed to the top six finishers, so while Alboreto scored a pair of fifths and a pair of sixths, he also racked up a frustrating string of six seventh places.

Alboreto quit Arrows after three seasons to join BMS Scuderia Italia for a disastrous year wrestling the Ferrari-powered Lola T93/30 at the very back of the grid. The veteran knew this luminous leviathan was a disaster right from its shakedown test. He told journalist Adam Cooper, “The first time I drove it I thought someone was playing a joke on me… It was big, heavy, no downforce – absolutely no downforce at all. I think it was the only F1 car of the modern era which worked on gravity, not aerodynamics! It was terrible just having to try and qualify the thing.”

Despite this, his rookie teammate that year, reigning Formula 3000 champion Luca Badoer, has good memories of 1993, primarily because of the chance to work with Alboreto. He said of his 37-year-old compatriot: "We spent a lot of time together – testing, practice, driving to and from hotels. I was only 22 and Michele was like a father to me. On track we would fight each other – there was no-one else to fight at the speed we were going! – but off track we were friends.

“It felt a little strange, though, because back in the 1980s, Alboreto was a famous name on TV in Italy, but now here he was, my F1 teammate. I wasn't surprised at how quick he still was, but I couldn't believe how much pleasure he got just from driving – even that car!”

Before the season finished, the team dissolved and merged into Minardi, where Alboreto spent his last F1 season. He scored a point with sixth place at Monaco, but for this prematurely gray-haired veteran, F1’s appeal was dissipating rapidly. Two weeks before Monaco, at Imola, one of his rear wheels fell off in pitlane and injured some Ferrari and Lotus mechanics, and a few days after that, he was in Brazil attending Senna’s funeral. This pair had despised each other back when they were fighting for wins and podiums, but as Albo’s star faded, they became friends. The 1994 calamities, including Roland Ratzenberger's death and Karl Wendlinger's devastating accident in Monaco, were always going to take a mental toll on a driver in his 14th year of F1. At year’s end, with 194 Grands Prix to his name and approaching his 38th birthday, Michele retired.

But only from F1. He couldn’t quit racing. A dismal season in International Touring Cars followed – some veteran open-wheel drivers adapt well to tin-tops, while others such as Michele do not. Then came three impressive drives in the inaugural season of the Indy Racing League, when the teams were using the uber-powerful one-year-old CART cars. But what Michele really desired was a return to endurance racing. The Scandia/Simon IRL opportunity had given him a taster, since the deal also included Daytona 24 Hour and Sebring 12 Hour drives in the gorgeous Ferrari 333SP.

It was the legendary Reinhold Joest who provided Albo with the golden opportunity he sought. Racing a Joest-run TWR Porsche WSC-95 at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1996 resulted in a DNF, but a year later, Michele took pole and, partnered by future Le Mans legend Tom Kristensen and former teammate Johansson, Le Mans victory was achieved.

"It was very satisfying," said Johansson. "It felt like Michele and I had closed our circle of friendship. Twelve years on from when we’d first become teammates at Ferrari, we were again working together and had won together – and in one of the biggest races in the world."

Joest was impressed and when Audi asked him to run its works sportscar team, Alboreto was one of his chosen drivers. It led to a happy and fulfilling new portion of his career, and a close bond with one of his co-drivers, Rinaldo “Dindo” Capello.

"You would never have known Michele had been a Grand Prix winner,” Capello told me a couple of years after his friend's death. “He didn't act like a superstar; he was so open and so friendly, and still quick. Because he was not doing the full American Le Mans Series, Michele had been driving in the dark much less than the rest of us and once he realized he had lost a bit of pace at night, he used to ask for an extra stint in the daylight and one less stint in the dark, so the car would not lose time. He didn't have a big ego.”

This pair, along with Allan McNish, took victory for Audi at Petit Le Mans in 2000 and then, with Laurent Aiello, conquered the Sebring 12 Hours in March 2001.

"I remember so clearly,” said Capello. “He was so incredibly happy on the podium, like an 18-year-old scoring his very first victory! That is the picture I will always remember.”

It was a mental image that would flash back with dreadful poignancy little more than a month later. Audi was conducting straight-line speed tests at the Lausitzring facility when Alboreto’s R8 suffered a puncture to its left-rear tire – possibly caused by a stone. At more than 200mph, the car’s tail started to slide, Michele corrected, but then the car ‘sat down’ on its affected corner, allowing the air to catch the flat underside of the R8. Police reports stated that it flew 100 meters, cleared the guardrail and landed upside down in a grass area. With the car’s rollhoop torn off, poor Albo didn’t stand a chance. He died aged 44.

"I was on my way to join Michele at Lausitz that day,” Capello sighed. “I was waiting at the luggage carousel when there was an announcement, 'Mr. Capello, please go to the information desk'. A few seconds later my wife called me and said, 'I think Michele has had a crash. It's on the news'.

"I tried his mobile number, then I called the doctor over at the track, and he told me what had happened. He said, 'Please do not come to the track, go straight to the hotel'. I just couldn't believe it. But then I got a call from Michele's wife, Nadia, asking if I could bring all his stuff home…"

As always in such cases, the grief felt by Nadia, their daughters Noemi and Alice, and the entire family, can only be imagined. The tributes from Albo’s former rivals, teammates and team colleagues were heartfelt and without reservation – he had been an excellent driver but also a lovely guy.

A shocked Berger, then competitions director at BMW, recalled: “I saw him not long ago, and he said, ‘Gerhard, what you’re doing is completely wrong. You should come with me and do long distance races. We’ll phone up Stefan Johansson and the three of us can go racing as a group!’ I said, ‘No, Michele, that’s what you do – I don’t want to hurt myself any more.’ Maybe he should have stopped racing some years ago, but he just couldn’t leave it, and he died doing what he loved.”

Rosberg said: “Outside of the guys I’ve actually worked with, in my life in motor racing there were two others I thought exceptional people, in every sense of the word. One was Elio [de Angelis] and the other was Michele.”

The Finn also said: “When [Alboreto] was at Ferrari, he was at the peak of his career, and he was very, very good. The problem was that the car just wasn’t good enough to win the championship, and so he finished second to Alain in ’85.”

That was a particularly golden year of F1, with wins divided up between six former or future World Champions – Prost, Lauda, Senna, Rosberg, Mansell and Piquet – plus de Angelis and Alboreto. While there are drivers who had the talent to be F1 champions but for a wide variety of reasons never accomplished the feat, there are also those who have great races – sometimes enough of them in one year to have a distant shot at the title – but who don’t quite make it to the summit.

In this latter category you’ll find Michele. No, he was not perennially on par with the aforementioned champs, although one wonders what it would have done to his confidence had he clinched a title. Instead, team politics or poor cars, while never corroding his love of driving, would blunt the edge of the motivation required to push to the nth degree. Whereas a Rosberg or Senna could bullheadedly wring the neck of a recalcitrant car just as they could shut off from intra-team strife, Albo just wasn’t built that way.

But make no mistake, on his best days he was a match for anyone, while also remaining an affable, loveable person of great modesty – and huge enthusiasm for the sport. That latter attribute is significant for it explains both Michele’s ability to maintain equanimity while driving some quite hopeless F1 cars during the nine winless years after his zenith, and also the fact that, post-F1, he wanted to try touring cars, Indy cars, and sports cars. This sheer love of driving fast is also why his final race was not the 2001 Sebring 12 Hours but a Lamborghini Trofeo event at Monza, and why he relished his role as not just an Audi driver, but also an ambassador for the brand: because it allowed him to dress like Tazio Nuvolari and demonstrate the mighty pre-War Auto Unions!

“He was one of the very few drivers who you could be friends with and a rival at the same time – a very difficult thing to do!” said a moist-eyed Prost the week after his old rival's death. “I met him first when we were both in Formula 3 in 1979 [and] in both F3 and F1 we competed in a good way.

"He was a very friendly guy, a lovely man. You just could not have a problem with him.”

Let that, too, be Michele Alboreto's legacy.