Among the six million Black people who moved out of the Deep South from 1916 to ’70, the “Great Migration” chronicled by Isabel Wilkerson in The Warmth of Other Suns, were the parents of Huey Newton, who would go on to head the Black Panther party, and the parents of Jimi Hendrix, who would go on to set his electric guitar, and the rock world, on fire.

There was, too, a revolutionary of a different stripe who emerged from that African American diaspora—the gangly son of Charles and Katie Russell, a couple who left Monroe, La., for Oakland in 1943. That was William Felton Russell, who learned his basketball chops on the Oakland playgrounds, refined them at the University of San Francisco and perfected them with the Boston Celtics.

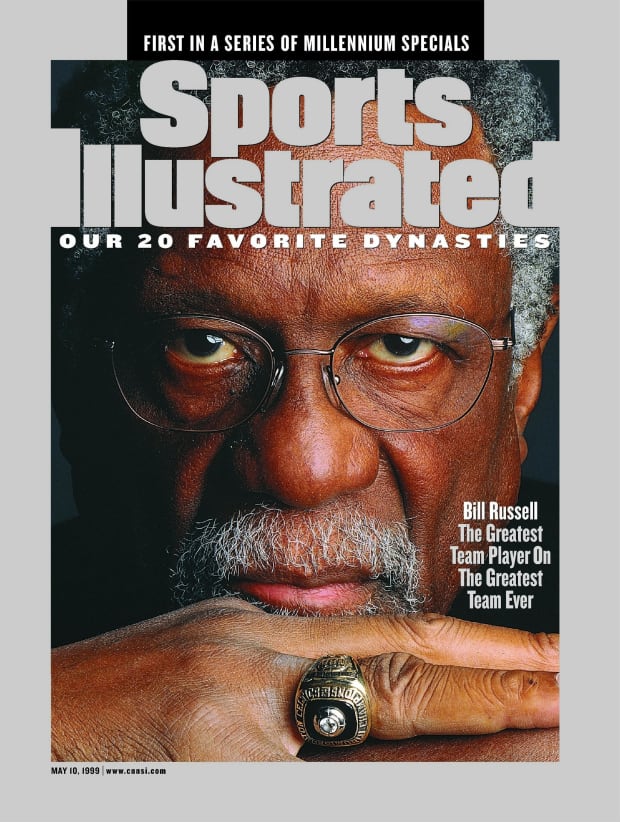

Bill Russell died Sunday at age 88 from age-related causes. His impact on the game was so profound that the NBA Finals MVP trophy is named in his honor.

Russell was just 9 when his parents arrived in Oakland, and so he had only a minor sense of the Jim Crow indignities that his parents had suffered in Louisiana. Charles Russell had a shotgun stuck in his face at a gas station, and Katie was told by a policeman to go home and change because she was wearing “white women’s clothing.” But the son came to know heartache and hard times on his own (his mother died when he was 12), and he would come to know virulent racism, too, especially after he arrived in 1950s Boston, a city that in some ways was not unlike Monroe, La.

The barriers that Russell faced as he put together a Hall of Fame career, and his pertinacious reaction to them, became a major part of his legacy. But it would be a mistake to let them obscure what Russell accomplished as a game-changing player. As was the case with Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and, later, LeBron James, what Bill Russell said off the court resounded in large part because of what he accomplished on it.

lJesse D. Garrabrant/NBAE via Getty Images

(It’s impossible to ignore that LeBron made headlines a couple of weeks ago when he accused Boston fans of being racist, which echoed what Russell had said decades ago. Of course, Russell had unpleasant receipts. During his playing days, Russell and his family returned to their home in the Boston suburb of Reading to find that burglars had broken in, spray-painted racial epithets on the wall, smashed some of his trophies and defecated in his bed.)

In his formative years, Russell, who was cut from his junior high basketball team, was more diligent than gifted. But he practiced hard in both basketball and track, and gradually his long-legged gawkiness, combined with his work ethic and intelligence, started to produce results. He became an outstanding high jumper at Oakland’s McClymonds High School—one of his rivals was a future crooner named Johnny Mathis from Washington High in San Francisco—and attracted some attention as a defensive-minded albeit low-scoring basketball center whose teammates included future Hall of Fame baseball player Frank Robinson. The only college basketball scholarship that was offered, however, came from the Jesuits at the University of San Francisco, and Russell jumped at the opportunity. There he would team with another defensive demon, guard K.C. Jones, to overwhelm college basketball. In their junior season, they won the opening game, lost to UCLA, then reeled off 25 straight wins en route to the NCAA championship. In their senior season, Russ, K.C. and the rest of the Dons ran the table, 27–0, crushing Iowa 83–71 in the championship game. The template was set for Russell to become (as he not so humbly said himself many times) the greatest winner in sports.

Across the continent, meanwhile, interest was much higher in a player two years younger, two inches taller, 50 pounds heavier and seemingly a hundred times more athletic than Russell. Everybody knew Wilton Norman Chamberlain, a breathtaking athletic phenomenon from Philadelphia, and everybody wanted him. An intense recruiting battle ended with Chamberlain enrolling at Kansas University in 1956, the year that Russell finished up his USF career with his second straight NCAA championship.

And so would begin a story line that carried through until Wilt’s death from heart failure in 1999: Wilt dominated the headlines, but Russell earned the championships.

sifullframe

Russell wasn’t the first great defensive center, but he was the first around whom an offense could be constructed from his defensive talents. When it came time for the 1956 NBA draft, Red Auerbach, then in his sixth year as Celtics coach/overseer and still looking for his first NBA title, saw this in Russell. Auerbach surrendered to the St. Louis Hawks two All-Star-caliber players, Cliff Hagan and Charles “Easy Ed” Macauley, in exchange for the 6'10" Russell.

The move might’ve said as much about the times as it did about Auerbach’s acumen for judging talent: The Hawks, who played in a deeply segregated city, acceded to the trade at least partly because they were getting two white players in place of one Black one.

Over the next 13 years, 11 of which resulted in championships, the Celtics’ fast break revolutionized basketball. Most often, Russell got the break started by blocking a shot, retrieving it—he prided himself on the strategic block more than the spectacular one—and throwing a precise outlet pass. But Russell also frequently got the rebound and joined the break, finishing it with a dunk at the other end. Once he grew into his body, nobody ever called him awkward anymore.

Over 963 regular-season games and another 165 in the playoffs—the left-handed pivotman was an ironman who averaged 42 minutes a game and was rarely injured—Russell’s understated greatness was the key to the Boston dynasty. Though Russell often felt that his talents weren’t recognized by the media and the fans, he was voted MVP of the league five times, one more, he was sure to have noted, than Wilt earned.

There is no better illustration of what Russell meant to the Celtics, and his knack for bedeviling his more talented nemesis Wilt, than his final game. It was May 5, 1969. Game 7 of the Finals at the Forum in Los Angeles: Russell in his final season with the Celtics, Wilt in his first season with the Lakers.

It had been an enervating year for Boston, Russell in particular. He was 34, beaten down by so many trips up and down the floor and also the mental burden of serving as the team’s player-coach, an honor that Auerbach had bestowed on him in 1966. The Celts had finished the regular season in fourth place in the Eastern Conference, and it was a minor miracle that they had gotten the Chamberlain–Elgin Baylor–Jerry West Lakers to a Game 7. It seemed a preordained victory for the Lakers, whose owner, Jack Kent Cooke, had ordered balloons to be released after the presumptive victory. They hung in netting on the Forum ceiling, a silent, inflated taunt that Russell and the Celtics noticed when they took the court.

Sure enough, the Celtics won 108–106, their seventh Finals victory without a loss over the Lakers since Russell came into the league. Russell had only six points in that Game 7 but played all 48 minutes and grabbed 21 rebounds. As for Chamberlain, he sat out the final six minutes, first after coming down hard on his right knee and requesting a breather, and then being kept on the bench by coach Butch Van Breda Kolff. It wasn’t quite fair, but the game seemed to say everything about Russell, and his almost mystical superiority over Wilt, at least in the win-loss column. Years later, West gazed at a photo of Russell, who stood hands on hips, taking a breather. “He looks almost regal,” said West, who was mesmerized by Russell’s ability to win the big one.

sifullframe

By the time of that final game, Russell had become a recognized political activist, a central character in the turbulence of the times, and in contrast to Chamberlain, who had been a Richard Nixon delegate to the 1968 Republican convention. Russell had spent the summer of ’68 living with Jim Brown in Hollywood as news from the chaotic Democratic convention washed over them like a tidal wave. Russell’s radicalization had begun in his boyhood in Oakland as he and his father, who became a steelworker after his wife died, endured the racial slights endemic of the time, and continued in college, where on one road trip Oklahoma City hotels had refused to provide service to the USF team because it had Black players.

But Russell’s desire to speak out against the system really took hold in Boston, where he couldn’t help notice that fans cheered him when he was on the Garden parquet but often vilified him when he wasn’t. Russell referred to Boston as a “flea market of racism,” writing in his 1979 autobiography, Second Wind: The Memoirs of an Opinionated Man, that the “city had corrupt, city hall-crony racists, brick-throwing, send-’em-back-to-Africa racists, and in the university areas phony radical-chic racists.”

Russell fought back in any way he could, earning him the passive-aggressive adjective that was so often hung on thinking Black athletes of that time—difficult. Russell never went in for the show-stopping antics of Ali, but he never made it easy for those he considered to be racist. When the Celtics retired his No. 6 in 1972, Russell insisted it be done in an empty Boston Garden with only his teammates around. And remembering the slights of a league in which a de facto segregation existed, he refused to attend his ’75 Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

Russell moved out of Boston after he retired and for four years (1973–74 through ’76–77) coached the Seattle SuperSonics with moderate success. He followed that with various NBA broadcasting gigs in the ‘70s and ‘80s. He was never comfortable, or very good, in that role, nor did his one appearance as host of Saturday Night Live in ’79 do much to alter the course of television comedy. Russell was coaxed back into the league in ’87 to become coach and general manager of the Kings but lasted only 58 games as coach (the Kings were 17–41 when he stepped down), though he hung around for another year as GM.

Over the next decade, Russell was more or less estranged from the league and remained at his home in Mercer Island, spending much of his time golfing. But encouraged by NBA commissioner David Stern, he gradually returned to the fold and became more and more of a fixture during All-Star weekends, the Finals and other NBA events. He remained wary and held the media at arm’s length, but he was approachable and often brightened a room with his distinctive high-pitched cackle that seemed to come out of nowhere. “The one thing I had to learn in this job,” said Jerry Reynolds, one of his assistant coaches during his brief time in Sacramento, “was how to become cackle-proof.” Stern also announced in 2009 that the Bill Russell NBA Finals Most Valuable Player would be handed out after the final game. It’s anyone’s guess how many of those Russell would’ve won—five? six?—had the award existed before 1969.

Stern also arranged a rapprochement between the two giants of the game, and in Wilt’s final years he and Russell appeared together at NBA events from time to time. In 2012 the league released a documentary about the night in 1962 when Wilt scored 100 points in a single game, and Russell did the narration. “He’s been gone for more than a decade,” intoned Russell near the end of the film, “and I still miss him.”

The same now will be said of Russell, who could never have scored 100 points in a single game, perhaps not over the course of three games. But he gazed at a different mountaintop. He wanted to be recognized as the greatest winner in sports. It is an argument he made often and one with enduring merit.