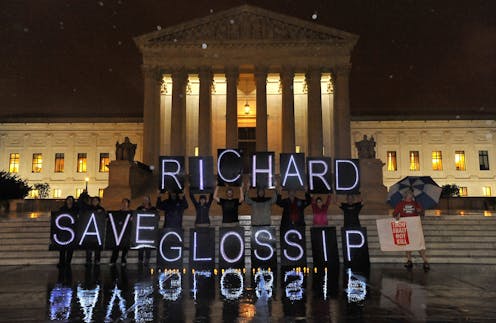

When the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board decided not to recommend clemency for death row inmate Richard Glossip, the case highlighted the role clemency plays in the death penalty system.

Glossip had asked the board to commute the sentence he had been given for his role in an alleged murder-for-hire plot. He was convicted of paying his co-defendant, Justin Sneed, to kill Barry Van Treese in 1997. Van Treese owned the motel where Glossip was the manager.

The board, which met April 26, 2023, was split 2-2 over recommending that Glossip’s sentence be changed to life in prison. The fifth member of the board recused himself because his spouse was involved in Glossip’s prosecution. A majority vote of three is required for a favorable clemency recommendation.

Because Oklahoma law does not permit clemency without a positive recommendation from the board, its decision sets the stage for Glossip’s execution on May 18.

From the start, Glossip, who had never before been arrested for any crime, maintained his innocence. His case has attracted wide attention, including from some of Oklahoma’s most conservative Republican legislators, who contend that if the state puts him to death it will be executing an innocent man.

Oklahoma’s case against Glossip rested on the testimony of Sneed, who was induced to be a witness with a promise of a reduced sentence. In addition, the prosecution destroyed evidence that would have supported Glossip’s claim of innocence, and new witnesses have come forward who further undermine confidence in the verdict.

An independent investigation by a law firm engaged by state legislators concluded that “no reasonable juror hearing the complete record would have convicted Richard Glossip of first-degree murder” and that his trial could not “provide a basis for the government to take … [his] life.”

Even the state’s Republican attorney general, Gentner Drummond, has said Glossip is probably innocent and that “it would be a grave injustice to allow the execution of a man whose trial was plagued by many errors.”

Drummond asked the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to vacate Glossip’s conviction and grant him a new trial. The court refused on April 20, 2023, which led to the parole board hearing the following week.

As someone who has studied the history of clemency in capital cases, I see three elements that make this case noteworthy: Attorney General Drummond’s actions, the attempt to use clemency to prevent a miscarriage of justice, and the fact that grants of clemency in death cases are today quite rare.

The role of the attorney general

Clemency hearings like Glossip’s are proceedings in which opposing sides – representing the condemned and the government prosecutors – present evidence and arguments. In Oklahoma, family members of the victim are also given time to make their views known.

In 1998, the U.S. Supreme Court gave its approval to that kind of procedure when it held that clemency hearings must afford due process to the participants. The court said the condemned person must be given an opportunity to convince a clemency board that the government should not put them to death – just as the government gets to defend its decision to do so.

And, as my research indicates, that is what the government has almost always done when its representatives participate in such a process.

But not in the Glossip case. Drummond, his state’s top prosecutor, took the unprecedented step of siding with the petitioner – even against other state officials.

“I want to acknowledge how unusual it is for the state to support a clemency application of a death row inmate,” Drummond told the Pardon and Parole Board. “I’m not aware of any time in our history that an attorney general has appeared before this board and argued for clemency. I’m also not aware of any time in the history of Oklahoma when justice would require it.”

Clemency as grace – or justice

I believe Drummond’s reference to justice would have surprised many of this country’s founders.

For them, doing justice was a matter for the courts. Clemency was about something else.

In United States v. Wilson, a decision from 1833 and the first case about clemency to be decided by the United States Supreme Court, Chief Justice John Marshall made that distinction clear. Instead of equating clemency and justice, he called clemency an “act of grace, proceeding from the power entrusted with the execution of the laws.”

Clemency, Marshall continued, “exempts the individual on whom it is bestowed from the punishment the law inflicts for a crime he has committed. It is … delivered to the individual for whose benefit it is intended, and not communicated officially to the court.”

A little more than 20 years after Marshall wrote that, another Supreme Court justice, James Wayne, reinforced this separation of clemency and justice. He noted that clemency was about “forgiveness, release and remission.” Wayne said it was a “work of mercy … [that] forgiveth any crime, offense, punishment, execution, right, title, debt or duty, temporal or ecclesiastical.”

But over the course of American history, both public and judicial understandings of the purpose of clemency have changed, with grace, forgiveness and mercy being replaced by justice.

Clemency, especially in capital cases, has come to be associated almost exclusively with correcting errors made in trials and other legal proceedings. Clemency hearings are now generally just another arena to which inmates like Richard Glossip can appeal for justice.

This view reached its height in the 1989 Supreme Court decision Herrera v. Collins, in which the court said that “A proper remedy for the claim of actual innocence … would be executive clemency” – a commutation or a pardon granted by a governor or the president.

Clemency, the court continued – using language that neither Marshall nor Wayne would have recognized – “is the historic remedy for preventing miscarriages of justice where judicial process has been exhausted.”

One example of this use of clemency occurred in 1998, when Gov. George W. Bush commuted the death sentence of Henry Lee Lewis after what Bush said were “serious concerns … about his guilt in this case.”

Clemency is rare in capital cases

Glossip, joined by Attorney General Drummond, sought clemency in the hope of preventing a miscarriage of justice like the one Bush cited as a reason to save Lewis’ life. Given the facts of Glossip’s case, what the Pardon and Parole Board did shocked many observers. But, from the perspective of clemency’s recent record in capital cases, the result should not have been surprising.

As my research has shown, a century ago clemency was granted in about 25% of capital cases. But in more recent years, according to the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center, clemencies in capital cases have been “rare.” The center notes, “Aside from the occasional blanket grants of clemency by governors concerned about the overall fairness of the death penalty, less than two have been granted on average per year since 1976. In the same period, more than 1,500 cases have proceeded to execution.”

While the center does not indicate how often clemency was sought in those cases, requesting clemency is often a standard part of the efforts death penalty defense lawyers make to try to save their clients.

It is hard to get clemency in capital cases because, as the center explains, “Governors are subject to political influence, and even granting a single clemency can result in harsh attacks.” As a result, “clemencies in death penalty cases have been unpredictable and immune from review.”

And what is true nationwide is also true in Oklahoma where during the past half-century there have been only five grants of clemency in capital cases.

Following the denial of clemency, Glossip’s lawyers have promised to keeping fighting and are asking both state and federal courts to stay his execution. Meanwhile Gov. Kevin Stitt has said he will do nothing to delay Glossip’s date with death.

Austin Sarat does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.