It was a busy day for Mitesh Patel and his wife Shweta in May 2018. Both 36, they were working from their home office in the Alamo Heights suburb of San Antonio while their two sons were at school and daycare. Shweta, a financial manager for a major medical group, was on a call. Mitesh, who managed assisted living facilities, was going over administrative reports.

Then Mitesh opened the email he’d been waiting 14 years for, from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ): An execution date had been set for Christopher Young, the man who killed Mitesh’s father. Hasmukh “Hash” Patel was fatally shot in 2004 at the family’s convenience store in Southeast San Antonio.

That email “felt like a sense of closure, a sense of relief for my family,” Mitesh said.

He read over the attachments to the email and told Shweta what he had said many times: He planned to attend the execution. Then he walked down the hall to tell his mother, who had lived with them since 2007.

Shweta remembers standing up to stretch at that moment. She was seven months pregnant with their third child, and it had become increasingly difficult to sit for a full day of work. It struck her that her due date was around the same time that Young was to be executed. She thought again of the message that had been hand-delivered by two men a few weeks earlier, from Young himself to Mitesh and his family. She wondered if it could possibly change her husband’s mind.

The execution date was two months away.

The facts about Texas’ death penalty are well-documented and, in many parts of the world, infamous.

The facts about Texas’ death penalty are well-documented and, in many parts of the world, infamous. The state has executed 577 people since 1976. What is less well known is that, once appeals have been exhausted and an execution date is set, the inmate’s lawyer can petition for clemency—a longshot attempt to reduce a defendant’s sentence, usually to life without parole. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles votes on the petition, then sends its recommendation to the governor. Few requests are granted.

A motley crew of people decided to try to stop Christopher Young’s execution. This is the story of that case—of a murder, a death penalty, and how the progress toward execution changed both the killer and the family of the man he killed.

Hasmukh Patel arrived in the United States in 1976, sponsored by his sister’s husband in Pennsylvania under a preference system for immigrants with needed skills and family ties in the United States. Raised in a family of farmers in Gujarat, India, he went to college, earned a bachelor’s degree in engineering and, in the 1970s, began fielding job offers from various countries.

His family arranged for him to marry the sister of his brother’s wife in 1975. Mina was seven years younger, a slight, smiling woman with glasses. They had a year together before he left for the United States, a time Mina remembers with pleasure: Hasmukh taking her to movies, ordering delivered meals instead of requiring his young wife to cook. Before he left, their first child, a daughter, was born. “I enjoyed that time in my life,” Mina said with a sigh.

In the United States, Hasmukh started working right away rather than continuing his education so he could send money home. His wife and daughter needed support, and his family had paid for a new water well that came in dry. He got a job flipping burgers at a Roy Rogers fast-food outlet for $2 an hour. His willingness to do whatever it took to support his family is something they remember.

Mina joined him in Pennsylvania a few months later, leaving their daughter with relatives temporarily. She, too, went to work right away, first in a sewing factory and later at other blue-collar jobs. For her, America was about working hard but also about being by her husband’s side. In 1981, a college friend invited Hasmukh to move to Houston for a job designing fire protection systems. Their daughter Rinal came to the United States that year, and Mitesh was born in 1982.

Hasmukh spent eight years in fire protection but never really found his niche. So, as other Gujarati Americans have done, he founded a small business. In 1988, he moved the family to San Antonio, where friends helped him lease a shuttered gas station in the southeast part of town.

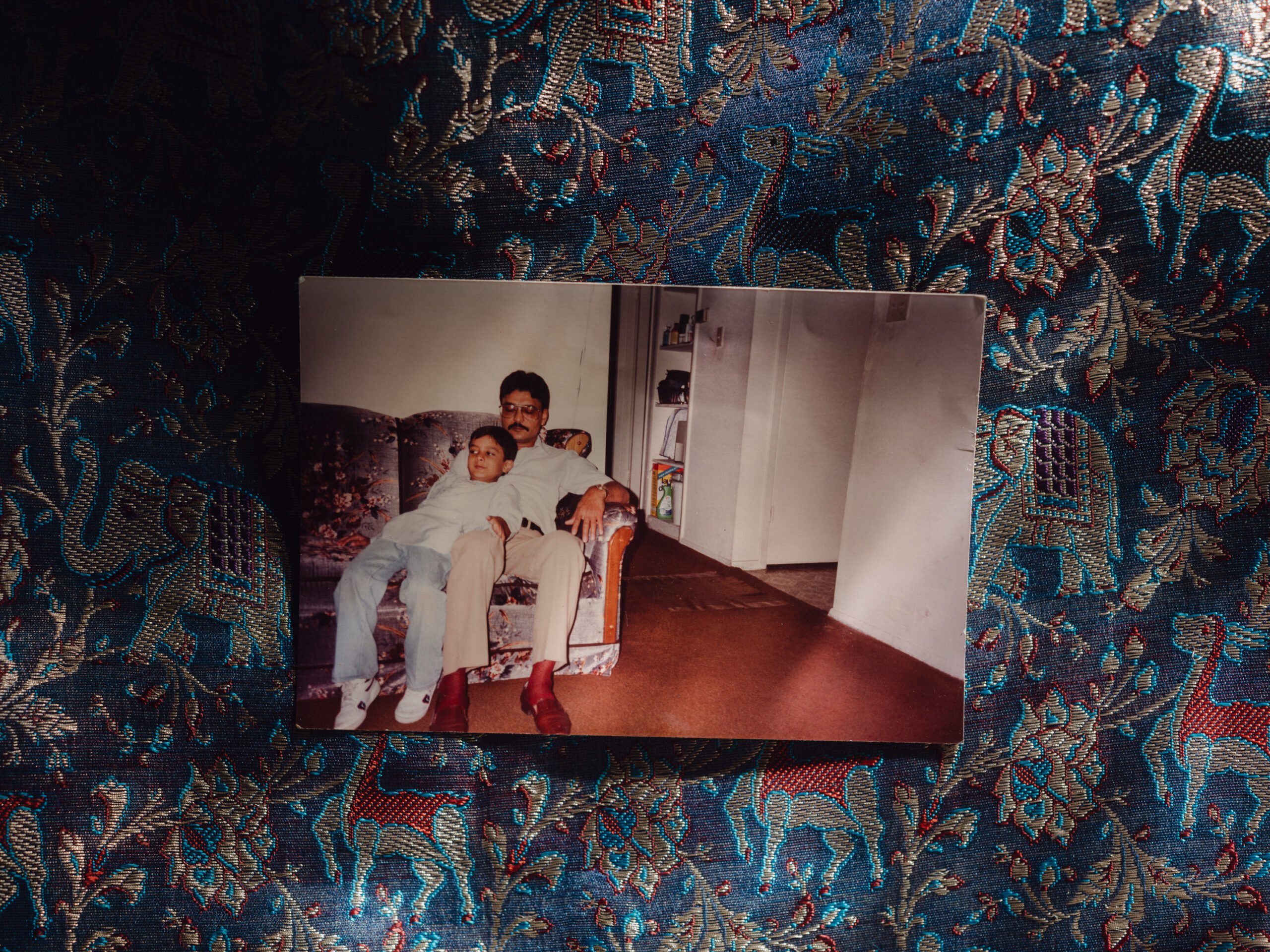

Mitesh, then 6, remembers the move— the borrowed cargo van, the eerie red glow over the empty gas station’s exit sign. With the help of family and friends, Hasmukh built a successful convenience store and dry-cleaning business there.

That store was young Mitesh’s universe. For 16 years, his parents were its main employees. If he or his sister were sick, his parents made them a bed under the front counter. The family moved into a two-bedroom apartment nearby, and both sets of grandparents joined them there from India shortly after.

“We lived with eight people in that apartment for years” before moving to a nearby home, Mitesh recalled. They had one car, a 1970 Buick Skylark that his father bought for $500. But Mitesh said that, as a kid, he never felt any sense of financial struggle, even when his father went through a series of layoffs before buying the store. Hasmukh never shared such worries with his family.

Mina would get the kids to school and then report to the store, working until it was time to pick them up. She learned to run the cash register and improved her English by talking with customers. For the first several years, the Patels were the area’s only Indian-American family, and they and their store were well known. Today, Texas has the second-largest Indian-American population of any U.S. state.

In Houston, Hasmukh and Mina had helped build a Swaminarayan Hindu temple, and they did the same thing in San Antonio. When the temple moved to an old church building, Hasmukh worked on the plumbing or in the garden—whatever was needed.

In the meantime, the neighborhood around the store was slowly changing, and so the store changed as well, selling more rolling papers than packs of cigarettes. There were some robberies, mostly kids trying to steal beer.

I felt like he transitioned from being my dad to really becoming my best friend.

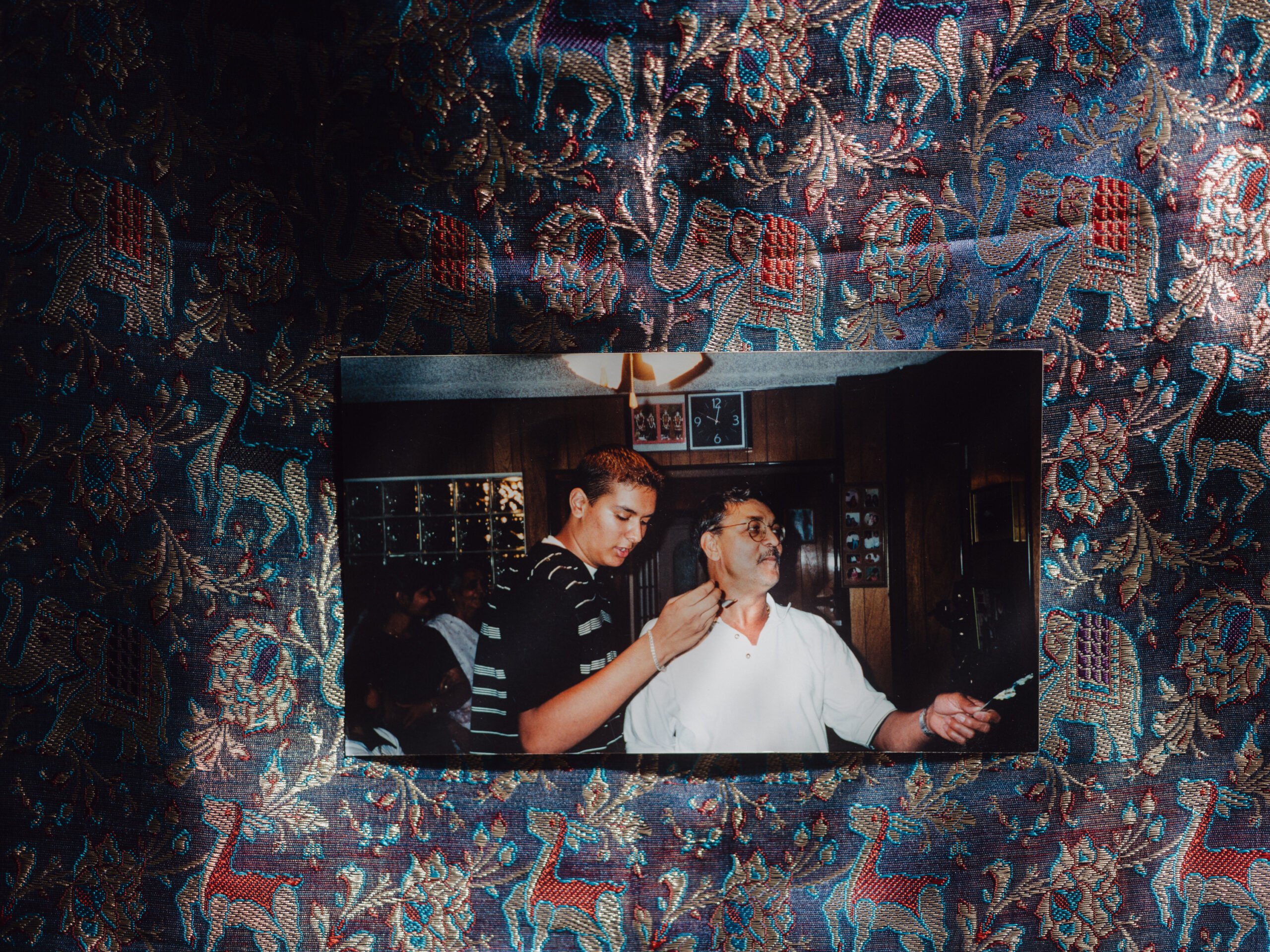

Mitesh began to resent his father’s 14-hours-a-day, seven-days-a-week work schedule and that so many of his own weekends were spent running store-related errands. When Mitesh intentionally failed three classes in high school, Hasmukh opened up to him about his own struggles, encouraging him to create something of his own. Eventually, he inspired Mitesh to become the businessman he is today. “I felt like he transitioned from being my dad to really becoming my best friend,” Mitesh said.

Hash, as his customers called him, was known for his generosity. If a customer came up short, Hash would often front them the money. Among the customers who benefited from Hash’s help were Christopher Young and his girlfriend. Mina advanced money to Young’s girlfriend for diapers for the couple’s baby. However, one day Hash and Young’s girlfriend got into an argument.

The next day was Sunday, November 21, 2004. Mina, on her way to the temple, detoured to bring chai to her husband. She remembers that he looked like a light was shining on him. “I could see his brightness,” she said. He had followed her to the car when a regular customer came by for a lottery ticket. “Today, my wife is first, then you,” he joked with the customer.

After Mina left, Young arrived, driving a stolen car. He had been drinking heavily the night before, and his girlfriend told him Hasmukh had disrespected her.

At the store, Young was angry and aggressive. When Hasmukh reached for the alarm button under the counter to call 911, Young shot him twice, killing him. Young left and was arrested later that day.

Mina heard the news, returned to the store, and fainted. Mitesh was living in Houston with his sister. They got to San Antonio as fast as they could.

Hundreds of people came to the funeral: Indian-American community members, dozens of customers. It was overwhelming for Mitesh; the Hindu rituals of touching the body before it was cremated drove home that his father was really gone. Mitesh couldn’t speak. He let his sister do the talking that day.

When Young killed Hasmukh Patel in a drunken haze, he arguably prolonged his own life. At 21, he was a self-professed “knucklehead” who’d grown up in poverty. A mental health evaluation diagnosed him with PTSD from major childhood trauma.

His mother had two children—Christopher was her second—before she was 18. She broke up with Christopher’s father, Willard Young, then moved the kids to Wisconsin, married again and divorced, and moved back to Texas after breaking up with yet another boyfriend. It was later discovered that one of her former partners had raped Christopher’s sister and another had abused Christopher. Being back in San Antonio meant Christopher got to spend time with his father—but not for long. In 1991, Willard Young was shot and killed, allegedly in a drug deal connected to his gang affiliation. Christopher was 8.

After that, Christopher “really lost his way,” said his aunt, Valerie Harris, Willard’s sister. He found a new father figure in an uncle who was also in a gang, so Christopher joined one too, associated with the Bloods. Soon after, according to Christopher, his uncle was sentenced to 50 years for the murder of a rival gang member.

I remember seeing my uncle … the day after he was shot … I have seen people get stomped out and have seen people get their ass beat.

In a 2014 psychological evaluation, Christopher spoke of growing up around the Bloods. “I remember seeing my uncle … the day after he was shot,” he told the evaluator. “He showed me the gunshot wound. … I have seen people get stomped out and have seen people get their ass beat.” He later attended a school dominated by the rival gang, the Crips. “I would have fights with Crips every day,” he said.

Not surprisingly, Christopher lost interest in school, though he was extremely bright. In middle school, he began to have run-ins with authorities, often due to fights with his mother. His aunt said he attempted suicide several times, feeling like he’d lost the only person who really loved him—his father.

According to documents put together for his clemency plea, by the time Young stopped attending school regularly, around the ninth grade, he had been a drug-dealing gang member for several years. When he was arrested for Hasmukh Patel’s murder, he was also charged with car theft (which he later admitted to) and sexual assault (which he denied). In his trial, prosecutors presented evidence about both the car theft and, in the punishment phase, about the assault charge.

On Texas’s Allen B. Polunsky Unit in Livingston, death row inmates live in single-person, 60-square-foot cells and are not allowed to work. They receive one hour of solo recreation per day. At least eight death row inmates have committed suicide in the past 20 years. Christopher would spend a dozen years in one of these cells.

His aunt believes Young’s transformation began on death row. Harris hadn’t seen him in years, but she wrote and began to visit him in Polunsky.

“When I first saw him, he was so angry,” Harris said. He learned from the other inmates how to protest when they were treated inhumanely. When inmates refused to move, a “force team” of guards came in to physically move them. Because force team actions had to be documented on video, inmates used the recordings as a tool to voice their grievances.

Another Polunsky inmate, Ronald Prible, writing in support of Young’s bid for clemency, recalled an incident when guards were punishing the person in the adjacent cell by denying food. In protest, Young “jacked his bean slot,” jamming the horizontal slot through which food trays are delivered. The force team was called, and Young was disciplined. The incident stuck with Prible because Young, who was Black, had been advocating for a white man.

“Most people here wouldn’t stick their necks out for anyone, especially someone of another race,” wrote Prible, whose death sentence was overturned in 2020 because of allegations of prosecutorial misconduct by a white prosecutor.

Harris said Young repeatedly looked out for fellow inmates. When he learned one of his neighbors was planning to kill himself, he stayed up all night and talked him out of it. He began to read incessantly, wrote, painted, and connected with fellow inmates and his family—especially his daughter Chrishelle, who was only 2 years old when he was sent to prison. Through his aunt, he began to connect with troubled young people outside prison.

When youths she knew were struggling with disciplinary or mental health issues, Harris started bringing them to Young. He would share his story but also encouraged them to find creative outlets. Those discussions sparked something in him.

“It was like he found a purpose,” Harris said.

Texas Innocence Network founder and attorney David Dow, with the help of another lawyer, students, and volunteers, handles the appeals of some Texas death row inmates and took on Young’s case in 2013. Dow said he found Young to be an exceptional person, “easily a guy who would’ve been a friend of mine if he hadn’t been on death row.”

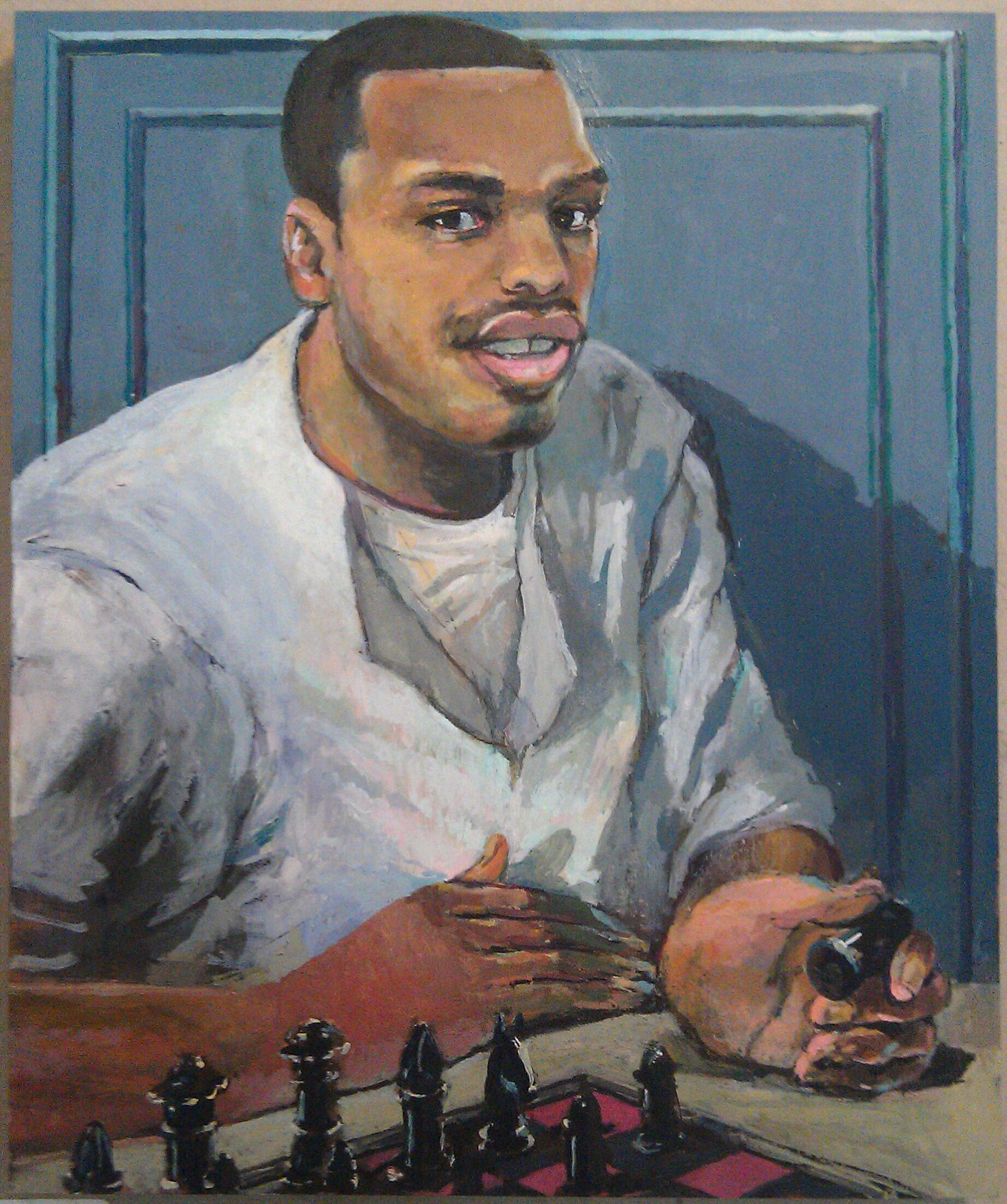

New York artist Peter Charlap had never thought much about prisons until he heard an NPR interview with Dow about his death row work. Wanting to help, he contacted Dow, who put him in touch with Young. Charlap began visiting the prison to paint portraits of the incarcerated.

When he first met Young, Charlap asked what he dreamt about in prison. Young’s answer was to ask whether the artist had read Carl Jung. “And I realized, I’m talking to a highly intellectual person,” Charlap said. “Very well read. Very charismatic.” His portrait shows Young behind a chessboard. Charlap was fascinated with how the men played chess in their separate cells, calling out moves to one another. He said Young could play four games at once.

In 2016, Los Angeles-based filmmaker Laurence Thrush and other writers were working on a pitch for a series based on Dow’s work, and Dow put him in touch with Young. They began corresponding, and while the TV show was never made, Thrush’s friendship with Young grew. They began collaborating on a documentary film. When Thrush met British actor and producer Chike Okonkwo (Being Mary Jane, La Brea), who had moved to Los Angeles and was increasingly interested in the criminal justice system, he introduced him to Young as well. Okonkwo found Young to be “kind and smart, artistic,” he said in an interview, and they, too, became friends.

Harris said the collaboration with Thrush built a fire under Young to bring about serious change. Thrush and Okonkwo, like Harris and Young, felt that the documentary could help troubled young men on the outside and also tell a story of the prison system from the inside.

Then the news came that Young’s execution date had been set.

When an inmate has exhausted all appeals, he is, in the lingo of Innocence Network workers, “on the brink” of having an execution date set. An inmate with an execution date is called a “crisis case.”

“We keep track of all of the cases that are on the brink, and we identify issues that we will raise if it becomes a crisis case,” Dow explained.

Dow’s team began to work on a clemency petition for Young to the Texas Board of Paroles and Pardons, whose five members make recommendations to the governor. They consider the defendant’s crime, the defendant’s behavior while incarcerated, and the wishes of the victim or victim’s family.

We manage to keep our clients alive for months and sometimes years … It’s time that they get to spend with their friends and their family and their loved ones.

Getting someone off death row doesn’t happen often—in 30 years, Dow has gotten 14 clients’ sentences changed from death to prison time and gotten four out of prison entirely. Even when he can’t do that, he said, “We still manage to keep our clients alive for months and sometimes years, sometimes many years longer than if we weren’t representing them. … It’s time that they get to spend [communicating and visiting] with their friends and their family and their loved ones.”

Dow had recently won relief for another client. Thomas Whitaker, a white man, had hired a hitman to kill his family for insurance purposes. His mother and brother were killed. His father survived the shooting and advocated for his son’s clemency. The Pardons and Paroles Board voted unanimously for clemency, and Governor Greg Abbott commuted Whitaker’s sentence to life in prison without parole.

Thrush and Okonkwo thought Young might have a good chance for clemency because his crime, unlike Whitaker’s, was not premeditated, and Young had transformed his life while on death row. They decided to ask Mitesh Patel for help.

Mitesh Patel was 22 when his father died, and he shouldered much of the murder’s fallout. He inadvertently saw the security video of Young shooting Hasmukh. Mitesh identified his father’s body and testified at trial to spare his mother and older sister Rinal the trauma of doing so. Over the next 14 years, whenever a major life event came along—marriage, becoming a father himself, business successes and failures—he drove to that store and sat in the parking lot, where he felt closest to his father.

He had kept tabs on Young’s case. “I was a typical Texan who was waiting for him to get executed,” he said with characteristic candor. “I really felt like the state was wasting all this time and money. This guy killed my dad with a 30-cent bullet. For years, I was like, ‘I will gladly provide the state with a 30-cent bullet and we can take care of this much, much faster.’”

Shweta and Mitesh had met in graduate school a few months before Hasmukh Patel was murdered, and she’d always felt the loss of not knowing this man who was so important to her husband. But Mitesh’s idea of attending the execution to achieve closure had never sat right with her. She feared it wouldn’t give him the relief he sought.

As the execution date approached, Okonkwo had begun to worry about the clemency team’s plan to show up unannounced at the Patels’ house. He talked to Rebecca Weiker, a transformative justice expert who told him that at all costs he should avoid retraumatizing Mitesh. Okonkwo and the others decided to leave a letter saying they had a message from Young.

The actor and Thrush drove to the Patels’ house, got out, and put the letter in the mailbox. But as they headed back to the car, Shweta came out to speak to them. Mitesh was out of town, but she wanted to know who they were. Okonkwo noticed that she was pregnant.

I was a typical Texan who was waiting for him to get executed.

“As soon as we told her who we were, and that we had the message, she started talking to us excitedly, saying that maybe this would help Mitesh,” he remembered. Shweta went inside and called Mitesh right away. He was furious that she would speak to and be manipulated by these strangers.

A few weeks later, Thrush and Okonkwo came back, asking if they could show Mitesh a video message from Young. This time, Mitesh agreed, they met for breakfast, and Mitesh watched the video. In it, Young says that killing Hash Patel was the biggest regret of his life, that he wanted Mitesh and his family to know how sorry he was. Mitesh recoiled at hearing his father’s name coming from Young’s mouth. He didn’t trust the video or these men.

Thrush tried to tell Mitesh what he knew of Young’s background, the hardship he had gone through as a child, and how much it would hurt his 14-year-old daughter Chrishelle to lose her father.

“I was like, ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’” Mitesh said. “They were presenting stuff to me about how Chris is this great artist, eloquent, how they visit him often and it just pissed me off—here are two people from Hollywood … and Chris is their pet project, and they are shitting on me and my family and what Chris did to my family with this ‘Oh, poor Chris’ take.”

When he saw the meeting derailing, Okonkwo changed direction. “I told him that there is real evidence that watching an execution can retraumatize people who [have lost] someone to murder,” Okonkwo said. “I told him that I was honestly worried about him.”

Mitesh remembers his reply. “I was like, ‘Worried about me? You don’t know me, man. Worry about your own damn self.’”

Dejected, Thrush and Okonkwo headed back to Los Angeles. Okonkwo, though, couldn’t stop thinking about Mitesh. Over the next few weeks, he emailed, texted, and called. Eventually, Mitesh started picking up the phone when Okonkwo called.

“He’s so damn persistent,” Mitesh recalled, laughing. “And he always came at me with such sympathy.”

On one call, Okonkwo told Mitesh about how Young, in visits with his daughter, always said he was in prison solely because of his own actions and that she should “stay away from people like me and find good people to surround you.”

After the call, Mitesh found himself staring into his computer screen. It was late. Shweta was already in bed; the pregnancy had been hard, and the fact that her due date and Young’s execution date were so close had started to bother him, too.

“I was like, ‘Holy shit, I’m a dad, and here is another guy who is a father, and he is trying to impart something positive to his daughter, and if the state takes him away, that fatherhood stops,’” Mitesh said, thinking of how much he missed talking to his own father. “I finally thought, if there is a chance for me to stop it, then I could help his daughter Chrishelle not go through what I went through.”

Mitesh went to the bedroom and woke Shweta to tell her. The next morning, he told his mother, who also agreed. Mitesh called Okonkwo back and said he wanted to help with the clemency attempt. Okonkwo connected him with Dow, who was surprised by the development. It wasn’t often that he saw this in Texas.

The execution was only three weeks away.

Over the next few weeks, with Okonkwo’s help, Mitesh attended rallies and spoke to local and national reporters. Thrush edited some of his footage into a video to accompany Dow’s legal brief. In addition to Young’s family members, it included testimony from 12 other Polunsky inmates attesting to the positive force he had become on death row.

Mitesh called TDCJ’s Victim Services Division to request a meeting with Young but was told that was impossible. Mitesh could write a letter, they said, and they would bring back Young’s recorded answers.

“It started to bother me, like, why can’t I go and talk to him?” Mitesh said. Both Victim Services representatives and the prosecutor who had tried the case contacted Mitesh to ask if he really wanted to do this. They warned him that Dow was known for theatrics, and they didn’t want Mitesh and his family to be manipulated.

“I really didn’t know who to trust at that point,” Mitesh said. It was “like everyone had their own agenda.”

Dow arranged for Mitesh to meet with the parole board in Austin. “They wanted to know why I was doing this and who had put me up to it,” Mitesh said. When Mitesh told them what he knew about Young’s early life, they told him about the man’s rap sheet and infractions from his early years in Polunsky. Mitesh left feeling as though he was doing something wrong.

A few days later, on Sunday, July 8, Shweta was feeling off and told Mitesh that she was going to take a nap. He got worried. Shweta said everything was fine, but he took her to the hospital anyway. Mitesh was right to worry: The baby was in the breech position and his heart rate was erratic. Shweta was rushed into surgery for an emergency cesarean section. They named the baby boy Rushabh Hasmukh Patel, after Mitesh’s father.

Shweta and the baby were still in the hospital when Okonkwo arrived to say he’d arranged for Mitesh to do an interview on Good Morning America. National pressure on Abbott might make a difference, but the interview was the next day. In New York City.

“I remember Chike asking me if it was OK if [he took] Mitesh, and I was like, no question—you have to go,” Shweta said. She had her parents and Mitesh’s sister to help.

When they arrived at the TV studio in New York, however, a producer said the story had been bumped for one involving former President Donald Trump and a Scottish golf resort. Shortly after, they got the news from Dow that the pardons and paroles board had voted unanimously to move forward with Young’s execution. The bid for clemency was over.

Okonkwo couldn’t believe that he had dragged Mitesh away from his newborn son for nothing.

But Dow had another idea. He and his team sued, claiming that the Texas Board of Paroles and Pardons’ action was racist, citing the evidence that they had voted in favor of Whitaker’s clemency, but ruled the other way when it came to an Indian-American victim and family and a black defendant. Dow pointed out other cases in which survivors of a victim opposed the execution of the perpetrator. In all the cases where the parties were people of color, he said, clemency was unanimously denied. However, in the case of Whitaker, a white man, it was unanimously granted.

The judge who heard the suit seemed bothered by those facts, Dow said. According to the Texas Tribune, U.S. District Judge Keith Ellison expressed frustration that he felt required to reject the appeal because Dow’s team had so little chance of proving racial discrimination.

Mitesh was on his way home from the airport when his cellphone rang. Someone from U.S. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee’s office was asking if he’d still like to meet Christopher Young in person. Mitesh said he would.

Later, Mitesh got an angry call from the head of Victim Services.

“He said, ‘I don’t know who you know, but I am on vacation out here on my ranch, and I got a call that I need to arrange a visit for you in Huntsville tomorrow, so you need to be there at 9 a.m. sharp,’” Mitesh recalled.

The next morning, Mitesh drove three and a half hours to the Walls Unit in Huntsville, where Texas executions are carried out. When he arrived, the parking lot was empty—the prison had been put on lockdown. A Victim Services staffer accompanied Mitesh to the meeting.

On the phone in a visitation room, separated from Mitesh only by a glass wall, Young apologized, saying that he should have never gone into the store that day and that Mitesh’s father should be alive. Mitesh asked questions about Young’s time in prison and about his daughter. Young told him how he’d tried to reach young people from inside prison.

I told him that I was sorry I didn’t come around earlier, that if we had more time, maybe I could have done more to make sure he got his sentence commuted.

“Then I apologized to him,” Mitesh said, “I told him that I was sorry I didn’t come around earlier, that if we had more time, maybe I could have done more to make sure he got his sentence commuted.”

Mitesh told him that he would be there as a witness the next day, not for closure or vengeance, but so Young did not have to die alone—and that he knew that’s what his father would have wanted.

Young held his hand up to the 3-inch-thick glass and motioned for Mitesh to do the same—their two hands similar in color and size. “You don’t have to do that. It was enough for you to have to watch your father die on that security video,” he told Mitesh, “I don’t want anyone to have to see that. I need to do it alone.”

Young took all his friends and family off the execution-day list, but he made his Aunt Valerie his spiritual advisor so she could be with him on July 17, in the hours before his execution. He was excited to tell her about his meeting with Mitesh. He called his family, who had all gathered in one place to say goodbye, which was joyful and painful.

“Then we got into an argument,” Harris recalled. She told him she would be there at the execution. He got mad and began to cry.

“It was the first time I had ever seen him cry,” Harris said, her voice breaking, so she backed down and agreed to stay away from the execution room. “He said, ‘But I’m not done yet.’”

Young told her he might fight the injection to protest the system one last time. But Harris said she understood now that she had been praying the wrong way in those last few days. Instead of praying for clemency, she should have been praying for peace.

“I said, ‘Baby, you don’t have to ever go back into that prison today. You gonna be free.’ … I said, ‘I’m not telling you not to fight, but fight with your words, think about the children. Show them the way with your words.’ I said, ‘Unless a seed is planted in the ground and dies, it bears no fruit. Be the seed.’ And he told me to go back to death row and tell his brothers to take the torch he had lit and run with it, and we prayed together, and I told him to go and take his rest.”

As she left to go to the chapel, she heard him laughing with the guards. Who does that, she thought. What kind of man can laugh with the guards that are going to kill him?

The Patel family had gathered in San Antonio. The two boys, Rishaan, 4, and Roshan, 2, played while the adults passed the new baby around. Before 6 p.m., Mina went to her altar.

Then the family fell silent as the TV news reported Young’s final words: “I want to make sure the Patel family knows I love them like they love me,” he had said. “Make sure the kids in the world know I’m being executed, and those kids I’ve been mentoring, keep this fight going.”

For days afterward, Harris couldn’t get out of bed or eat. But she made the trip to Polunsky a few days later. She visited all of her nephew’s closest friends and told them about his final day, sat with them as they cried and mourned, and made plans to continue his outreach work.

Thrush and Okonkwo were banned from visiting Polunsky because they’d used footage from the documentary to advocate for Young.

A year and a half after Young died, the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the country and shut down normal life, making it hard to visit Polunsky. But Harris kept up her work. Today, the Christopher Young Foundation: Love, Forgiveness, and Second Chances has its 501(c)(3) classification as a formal nonprofit organization.

Work continues on the documentary. Thrush said Young’s story will be there for future generations to learn from. Mitesh and Okonkwo remain close. They text each other often and talk about how they can make a change together somehow.

“People get it wrong,” Mitesh said. “I never forgave Chris for killing my dad, but I thought there was value to his life and that he was trying to do something good for his daughter, for other kids.” He wants to share his story in the hope that others will help him “make a change in this world as a way to honor my father and the values he instilled in me.”

Correction, September 26, 2023: In print and previous online versions of this article, we incorrectly referred to David Dow as the founder of the Texas Innocence Project. David Dow is actually the founder of the Texas Innocence Network.