The story so far: The prime accused in the Swathi murder case, P. Ramkumar, was found dead inside Chennai’s high-security Puzhal Central prison in 2016. Officials claimed he killed himself by “pulling and biting into a live electric wire”. Mr. Ramkumar’s father, however, alleged that it was an act of homicide.

In August this year, the Supreme Court Committee on Prison Reforms found suicide to be the leading cause of ‘unnatural’ deaths — deaths other than ageing or illnesses — among Indian prisoners, with Uttar Pradesh recording the highest number of suicides between 2017 and 2021. “...the number of custodial deaths has seen a steady rise since 2019, and 2021 has recorded the highest number of deaths so far,” their report stated. Other ‘unnatural’ causes of death include murder by inmates, death due to negligence or excesses, and ‘accidental deaths’, among other reasons. On the other hand, ‘natural deaths’ — 1,879 people in 2021 — includes ageing and illnesses.

The Hindu looks into trends of natural and unnatural deaths, and why experts think these numbers paint a grim picture of the state of healthcare and safety inside India’s prisons.

How are prison deaths classified?

Prison deaths are labelled as ‘natural’ or ‘unnatural’ by the Prison Statistics India report published by the National Crime Records Bureau every year. In 2021, a total of 2,116 prisoners died in judicial custody, with almost 90% of cases recorded as natural deaths.

‘Natural’ deaths account for ageing and illness. Illness has been further subcategorised into diseases such as heart conditions, HIV, tuberculosis, and cancer, among others. As the prison population swells, recorded natural deaths have increased from 1,424 in 2016 to 1,879 in 2021.

‘Unnatural’ deaths are more diverse in classification, profiled as:

- Suicide (due to hanging, poisoning, sellf-Iinflicted injury, drug overdose, electrocution, etc.)

- Death due to inmates

- Death due to assault by outside elements

- Death due to firing

- Death due to negligence or excesses

- Accidental deaths (natural calamities like earthquakes, snakebites, drowning, accidental fall, burn injury, drug/alcohol consumption, etc.

The suicide rate among inmates was found to be more than twice that recorded in the general population, per a report by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI). After suicide, most unnatural deaths are due to “other” reasons or murder by inmates.

While the NCRB data documents the socio-economic background of the inmate population (one in every three under-trial prisoners is either from a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe, per a study, and most lack the education and means to afford bail), the caste or religious profile of people who died is unknown.

An ‘unclear’ distinction

In a landmark Supreme Court judgment that drew attention to hostile prison infrastructure which results in custodial deaths, Justice M.B. Lokur said NCRB’s distinction between natural and unnatural deaths is “unclear.”

“For example, if a prisoner dies due to a lack of proper medical attention or timely medical attention, would that be classified as a natural death [due to illness] or an unnatural death [due to negligence]?” he asked.

This ambiguity, coupled with the fact that prison deaths are under-reported and rarely investigated, results in a majority of deaths being classified as ‘natural’, media reports have noted.

During the pandemic, the PSI report classified deaths due to COVID-19 as ‘natural’ deaths — at a time when the occupancy rate of prisons was 118% of their capacity, and almost 40,000 more undertrials were held in prisons, in comparison with the previous year. The same year, the sanctioned strength of medical staff was around 1:125, but in reality, one staff member was looking after 219 inmates. “... the failure to adequately test and treat those infected would arguably amount to ‘death due to negligence’ of the state,” scholars Saranga Ugalmugle and Ancy Susan George wrote in The Wire, even though the deaths were classified as natural.

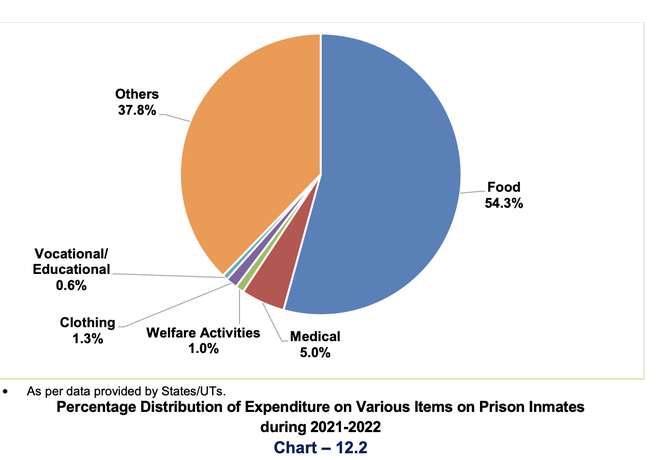

Moreover, as Justice Lokur and previous judgments have pointed out, the issue of custodial deaths — why they occur and how they are investigated — is intertwined with how congested prisons are, if inmates have access to medical help, whether there is adequate staff and whether the available staff is properly trained to aid inmates. Only 5% of expenditure is spent on medical facilities, per the PSI 2021 report. Moreover, between 2016 and 2021, money earmarked for spending on inmates was underutilised: ₹6,727.30 crore was the average national expenditure against a sanctioned ₹7,619.2 crore in 2021. In States like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab and Maharashtra, less than ₹20,000 was spent on each prison inmate in 2019-20, as this chart shows.

The infrastructural deficiencies are both a cause and effect of “callousness and neglect of the health of individuals in jail custody,” scholar Meenakshi D’Cruz argued in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. She notes that the ultimate refusal to provide care results in ‘unnatural’ deaths inside prisons, which are otherwise ascribed to ‘natural’ causes.

The neglect could be medical, psychological or a continued denial of access to healthcare, food or safety. In 2012, 32-year-old Pratap Kute was arrested for rioting and house trespassing and died a month after entering jail. His apparent cause of natural death, per the postmortem report, was ‘Pulmonary Koch’s with Miliary Tuberculosis of Liver and Spleen in Sero Positive Case.’ However, as Ms. D’Cruz noted, there was no evidence of whether a medical officer visited Mr. Kute or if there was a health screening at the time of admission. The police official refused to transfer Mr. Kute to a hospital for advanced care, stating that the police would “have no grievance if the life of the deceased Pratap was in danger” A Bench of the Bombay High Court in 2023 censured this chain of negligence which reflected the “total callous and insensitive mindset of the police authorities as well as the jail authorities.”

How are deaths investigated?

Since 1993, the NCRB is required to intimate a custodial death within 24 hours, followed by post-mortem reports, magisterial inquest reports or videography reports of the post-mortem. Further, if “an enquiry by the Commission into custodial death discloses negligence by a public servant, the Commission recommends to authorities of Central/State Governments for paying compensation to the Next of Kin (NoK) and also for initiation of disciplinary proceedings/prosecution against the erring public servant,” the Home Ministry said in response to a Lok Sabha question in 2022. The same response noted that only one ‘disciplinary action’ was taken between 2021-22 against an “erring official.”

In cases of custodial rape and death, the Code of Criminal Procedure also requires compulsory judicial magisterial inquiry in place of an executive magistrate inquiry. The National Human Rights Commission in 2010, however, weakened the legal requirement to say inquiry by a judicial magistrate is “not mandatory” when “there is no suspicion or foul play or where there is no evidence or allegation of an offence.”

Ms. D’Cruz noted the need for clear and reliable documentation, greater transparency and accountability. Only a robust reporting system can demarcate how many natural deaths result from pre-existing issues, “how many from conditions developed in prison; whether treatment was given, and whether it was adequate,” she says.

What has the government done so far?

The Supreme Court in a 1996 judgment articulated the social obligation towards prisoners’ health, noting that they suffer from a “double handicap”: ”First, the prisoners do not enjoy the access to medical expertise that free citizens have. Their incarceration places limitations on such access; no physician of choice, no second opinions, and few if any specialists. Secondly, because of the conditions of their incarceration, inmates are exposed to more health hazards than free citizens.”

The Model Prison Manual of 2016 and the Mental Healthcare Act of 2017, outline inmates’ right to healthcare, which includes adequate investment in healthcare facilities, setting up mental health units, training officers to provide basic and emergency care, and formulating suicide prevention programmes to thwart such instances. In light of rising suicide cases, the NHRC in June this year issued an exhaustive 21-page advisory to States, highlighting that suicides arise out of both medical and mental health issues. The Supreme Court Committee on Prison Reforms made similar recommendations.

An infrastructural issue common to all is the need to scale both quantity and quality of staff, as several reports flag ‘overflowing prisons’ with inmate count exceeding capacity in at least 26 States. The NHRC recommended filling positions of “Prison Welfare Officers, Probation Officers, Psychologists, and Medical Staff,” further noting that “the strength should be suitably augmented to include Mental Health professionals.” There is an acute shortage of staff: a sanctioned staff of 3,497 people (out of which only 2,000 roles were filled), was responsible for looking after 2,25,609 prisoners in 2021 (this number has shot up to 5,75,347 as of September 2023, according to the National Prisons Information Portal). Vacancies too are unevenly distributed: States like Bihar and Uttarakhand had over 60% of positions lying vacant. Moreover, the total strength of staff includes personnel charged with medical, executive, correctional, ministerial and other duties; not everyone is trained to provide medical aid.

The Model Prison Manual also specifies the needed bed strength, a pathology laboratory, qualifications and the number of medical officers and nursing assistants, and their precise duties, but most jails lack well-equipped prison hospitals.

Another recommendation is to allow inmates an “adequate number of telephones” with friends and family; judgments also note that prisoners should be allowed access to newspapers or periodicals to “reduce the feeling of isolation” and “possibility of harmful activity.” Authorities have denied such literature — including a P.G. Wodehouse book to Gautam Navlakha — citing “security risks”.

To prevent suicides specifically, guidelines recommend a strict check on tools such as ropes, glasses, wooden ladders, pipes; initial mental health screening at the time of entry into jail; and installing CCTV cameras to monitor high-risk inmates. Human rights activists have cautioned against the latter measure, as heightened surveillance would violate the rights of prisoners. Almost 1.5% of the prison population suffers from mental illnesses, per the CHRI report. It flagged a dearth of correctional staff including psychologists, “limited access to mental healthcare resources”, inadequate identification of mental illnesses in inmates along with heightened vulnerability and stigma.

Ms. Cruz points out major overhaul is possible only structurally: “both the public and official mindset regarding prisoners and an urgent revamping of the criminal justice system are sorely needed.”