Earlier last month, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Home Affairs, examining the three new criminal law Bills set to replace the Indian Penal Code (IPC), Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), and the Indian Evidence Act, recommended the criminalisation of adultery but on gender-neutral lines. This follows almost five years after a five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously decriminalised adultery in 2018 on several grounds including discrimination.

The new Bills were introduced in the Lok Sabha on August 11 to reform the colonial-era criminal laws now in place and were then referred to a 31-member Parliamentary Standing Committee, headed by BJP MP Brij Lal, for scrutiny. After consulting experts and stakeholders, the Committee adopted its report on the Bills on November 7, with Opposition MPs pointing out several errors and recommending more than 50 changes. In their dissent notes, the Opposition MPs flagged the lack of diversity of the domain expert opinion, questioned the haste with which the new laws are being introduced, and highlighted that the new legislations are ‘largely a copy-paste’ of the existing laws.

The Committee reasoned that adultery be criminalised in a gender-neutral manner on the ground that it is crucial to safeguard the sanctity of the institution of marriage. Opposition MPs have however refuted this claim by underscoring that it is “outdated to raise marriage to the level of a sacrament” and that the State has no business to enter into the private lives of couples and punish the alleged wrongdoer.

Parliamentary panel’s recommendations

In its 350-page report, the Committee suggested that adultery be reinstated as a criminal offence, but be made gender-neutral, thereby making both men and women equally culpable under the law. Highlighting the need to protect the institution of marriage, the report stipulates, “..the Committee is of the view that the institution of marriage is considered sacred in Indian society and there is a need to safeguard its sanctity. For the sake of protecting the institution of marriage, this section should be retained in the Sanhita (Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita) by making it gender neutral.”

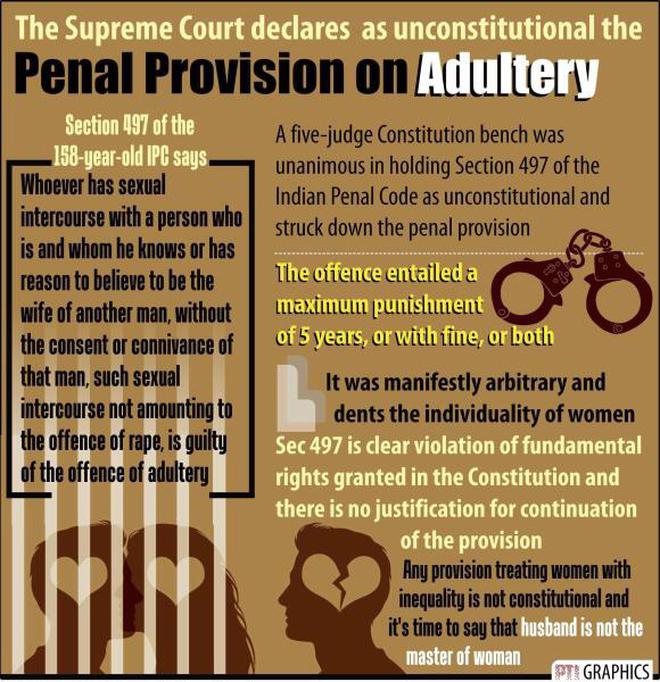

The Committee also pointed out that the revoked Section 497 of the IPC “only penalised the married man, and reduced the married woman to be a property of her husband”. The proposed change also seeks to address this deficiency.

Dissent notes

In his dissent note to the three Bills, Congress MP and former Home Minister P. Chidambaram emphasised that interference by the State in the private lives of consenting adults must be avoided.

“Adultery should not be a crime. It is an offence against marriage which is a compact between two persons; if the compact is broken, the aggrieved spouse may sue for divorce or civil damages. To raise marriage to the level of a sacrament is outdated. In any event, a marriage concerns only two persons and not society at large. The State has no business to enter into their lives and punish the alleged wrongdoer,” the note reads.

Legislative history

When the IPC was enacted, Hindus had no law of divorce as marriage was considered to be a sacrament. It made little sense to punish a married man for having sexual intercourse with an unmarried woman as he could easily marry her later since Hindu men were permitted to marry any number of wives till 1955. However, with the advent of the Hindu Code, a Hindu man was allowed to have only one wife and as a result adultery became a ground for divorce in Hindu Law.

Lord Macaulay, instrumental in the early drafting process of the IPC, was not inclined to make adultery a penal offence, believing that a better remedy lay in pecuniary compensation. He acknowledged that given the sacramental nature of marriage in India, the law was not the solution in dealing with marital infidelity. Distinguishing between a moral wrong and an offence, he wrote, “We cannot admit that a Penal code is by any means to be considered as a body of ethics, that the legislature ought to punish acts merely because those acts are immoral, or that because an act is not punished at all it follows that the legislature considers that act as innocent.”

Subsequently, when the Court Commissioners reviewed the Penal Code, they believed it was important to make adultery an offence. The proposed section however rendered only the male offender liable, keeping in mind “the condition of the women in this country” and the law’s duty to protect it.

In 1971, the Law Commission of India in its 42nd Report deliberated on the benefits of criminalising adulterous conduct. It, however, noted, “Though some of us were personally inclined to recommend repeal of the section, we think on the whole that the time has not yet come for making such a radical change in the existing position.” Notably, there was a strong dissent by Anna Chandy, who voted to revoke the provision saying it was the “right time to consider the question whether the offence of adultery as envisaged in Section 497 is in tune with present day notions of woman’s status within marriage.”

The Commission did, however, recommend an important amendment — removal of the exemption from liability for women. Such a recommendation was reiterated in its 156th Report, taking into account the ‘transformation’ society has undergone. It also highlighted the need for procedural reforms to remove the bar against women from initiating prosecutions. However, such proposals were not reflected in either the 41st Report (which led to the Cr.P.C.) or the 154th Report which reviewed the Cr.P.C.

In 2003, the Committee on Reforms of the Criminal Justice System, popularly known as the Malimath Committee, proposed in its report that adultery be retained an an offence but on gender-neutral terms. It observed, “..object of the Section is to preserve the sanctity of marriage. Society abhors marital infidelity. Therefore, there is no reason for not meting out similar treatment to the wife who has sexual intercourse with a man (other than her husband).”

‘A matter of privacy’

A five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court led by then Chief Justice of India (CJI) Dipak Misra, and comprising current CJI D. Y. Chandrachud, and Justices A. M. Khanwilkar, R. F. Nariman, and Indu Malhotra, in its landmark judgment Joseph Shine v. Union of India (2018), held that adultery is not a crime and struck it off the IPC. It, however, clarified that adultery would continue to remain a civil wrong and a valid ground for divorce. In 2020, a five-judge Bench led by former CJI Sharad A. Bobde dismissed petitions seeking a review of the verdict for lacking merit.

The inception of the proceedings dates back to 2017 when Joseph Shine, a non-resident Indian, hailing from Kerala, filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) under Article 32 of the Constitution, challenging the constitutional validity of the offence of adultery under Section 497 of the IPC read with Section 198(2) of the Cr.P.C. The offence imposed culpability on a man who engaged in sexual intercourse with another man’s wife and was punishable with a maximum imprisonment of five years. However, the wife who had consented to sexual intercourse with a man, who was not her husband, was exempted from prosecution. The provision was also not applicable to a married man if he engaged in sexual intercourse with an unmarried woman or a widow. Notably, Section 198(2) of the CrPC empowered only the husband (of the adulterous wife) to file a complaint for the offence of adultery.

In July 2018, the Centre filed an affidavit in the case arguing that diluting adultery in any form would weaken the institution of marriage and that the ‘stability of a marriage is not an ideal to be scorned’. On September 27, 2018, the Bench pronounced a unanimous ruling in the form of four concurring judgments.

Former CJI Dipak Misra (writing for himself and Justice A.M. Khanwilkar), highlighted that adultery is not a crime if the cuckolded husband connives or consents to his wife’s extra-marital affair, thereby treating a married woman as her husband’s ‘chattel’. Underscoring that adultery is “absolutely a matter of privacy at its pinnacle,” the judge reasoned, “If it is treated as a crime, there would be immense intrusion into the extreme privacy of the matrimonial sphere. It is better to be left as a ground for divorce.”

Justice R.F. Nariman, in his concurring opinion, observed that Section 497 made a husband the ‘licensor’ of his wife’s sexual choices and that this archaic law does not square with today’s constitutional morality. He added that the offence perpetuates the gender stereotype that the ‘third-party male’ has seduced the woman, and she is his victim.

Reiterating similar concerns, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud held that the criminalisation of adultery subjugated the woman to a position where the law disregarded her sexuality. He reasoned, “Marriage does not mean ceding autonomy of one to the other. The ability to make sexual choices is essential to human liberty. Even within private zones, an individual should be allowed her choice.”

Notably, Justice Indu Malhotra was categorical that the autonomy of an individual to make his or her choices concerning his/her sexuality in the private sphere should be protected from criminal sanction. She explained that adultery although a moral wrong qua the spouse and the family, however, does not result in any wrong against the society at large in order to bring it within the ambit of criminal law.

Agreeing with this, lawyer Saurabh Kirpal points out that criminalisation would amount to the “State entering the bedrooms of two individuals.” He instead highlights that adultery should remain as a ground for divorce if one believes in a conservative framework of marriage. “It is difficult for a woman to live with a man who is cheating on her. But that’s between two private parties,” he says.

According to senior Advocate Gopal Sankaranarayanan, there are multiple reasons why a woman would not want to have conjugal relations with her husband — which include instances of abuse or domestic violence. But such a woman can’t have sex outside the marriage, thus resulting in the criminalising of natural bodily needs, he asserts.

Not a ‘crime’

Mr. Kirpal further highlights that the purpose of criminal law is to ensure that there is no harm to the public at large. Emphasising that in a liberal society, “personal choices should be protected by the law”, he says that criminalisation would not necessarily command respect for the rule of law since “adultery is far more common than we think”.

Advocate Bharat Chugh points out that in some countries adultery is a tort or civil wrong, thus allowing people to sue for damages “because someone took away your affections.” Since India is a common law country, we could do that here, he says, although noting that there is no precedent or judgement to this effect here.

Undue importance given to marriage as an institution

Underscoring that the origin of the law dates back to the Victorian sense of morality, Mr. Sankaranarayan says that the “over-importance of marriage should be ended” and that “there is no scope for it in criminal law.” He, however, carves out an exception in the limited scope of dowry.

He points out that exceptions have been made in law due to the fact of marriage — ‘Rape is a crime otherwise, but a man can rape a woman if she is his wife. Similarly, if a man and woman are living together, and one of them cheats on the other, it doesn’t become an offence.’

Mr. Kirpal flags that the recent recommendation shows the doublespeak of both the Parliament and the courts. The judgment of the Supreme Court in Supriyo devalues the right to marriage. If marriage is not even a fundamental right, curtailing the right of any two people to have sex in order to protect the sanctity of marriage— makes little sense, he says.

Gender neutrality doesn’t fix the problem

The problem with adultery being in IPC was two-fold, Mr. Sankaranarayan points out. The first is criminalising it on the basis of the institution of marriage and the second is treating women as property. Making it gender neutral would do away with the second— taking away “the patriarchy bit” as Mr. Chugh says, but still leave the first.

“It would apply to all relationships you are recognising as marriage — including heterosexual marriages between transpeople as envisaged by the judgment in Supriyo v. Union of India”, Mr. Kirpal says.

As to how a gender-neutral provision may impact members of the LGBTQ community, Mr. Chugh points out that unless relationships are recognised as marriage, people cannot be prosecuted. “But once they are, they will be,” he says.

Why is it being re-introduced now?

When asked about why it may have been reintroduced now, after the SC struck it down in 2018 and after the recent judgment pertaining to same-sex marriage, Mr. Kirpal says that it shows a certain mindset. The Parliament is trying to control choices related to bodily autonomy, he notes. “Society may frown on it, but that is no reason to automatically criminalise it,” he says, adding that in this way, it is very similar to section 377 of the IPC.

Legislative overruling of judicial pronouncements

A ruling of the Supreme Court establishes a precedent and binds the lower courts to follow its dictat. However, the Parliament is well within its scope to overrule judicial rulings, but such legislative action will be considered valid only if the legal basis of the judgment is altered. Elaborating on this, the Supreme Court in Madras Bar Association v. Union of India (2021) held that “the test for determining the validity of validating legislation is that the judgment pointing out the defect would not have been passed if the altered position as sought to be brought in by the validating statute existed before the Court at the time of rendering its judgment. In other words, the defect pointed out should have been cured such that the basis of the judgment pointing out the defect is removed. “

In September this year, a division bench of the Supreme Court in NHPC Ltd. v. State of Himachal Pradesh Secretary reiterated that the legislature is permitted to remove a defect in an earlier legislation, as pointed out by a constitutional court, and that laws to this effect can be passed both prospectively and retrospectively. However, the court cautioned, ‘..where a legislature merely seeks to validate the acts carried out under a previous legislation which has been struck down or rendered inoperative by a Court, by a subsequent legislation without curing the defects in such legislation, the subsequent legislation would also be ultra-vires.’