The best place to start, when someone wants to tell the Iliad-like epic tale of how the sojourning Rangers won their first World Series championship seemingly without warning, is the end, as a son falls into the arms of his father, tears streaming down the son’s cheeks.

“You did it,” Damien Semien whispered into his son’s ear. “I am so proud of you. I love you.”

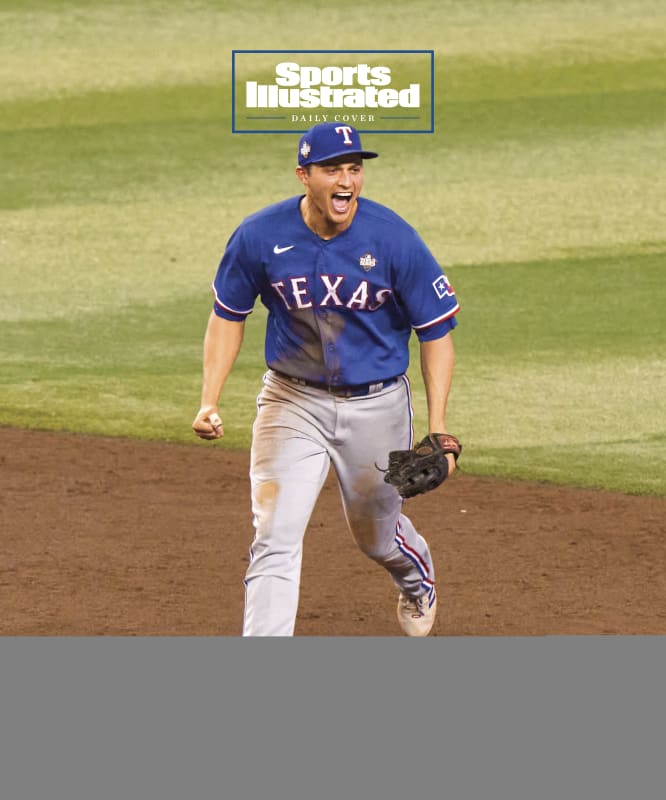

Damien was a football player at Cal. His son, Marcus, a second baseman for the Rangers, fell into his embrace as if subsumed by the curl of an ocean wave. So emotional was Marcus that his powerful hands quivered as he held tight to his father. The tears flowed. His mother, Tracy, watched the men clench, neither one able nor willing to let go.

“They raised me,” Marcus says. “For them to see this ...”

He stopped. He dabbed at his eyes.

“It feels so good,” he says. “They’ve seen me playing since Little League, since I was 6 years old. And now I’m a father myself and a World Series champion. When you see your loved ones after something like this, you kind of just lose it for a second.”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

The reasons why Texas beat Arizona in five games, capped by a 5–0 win in the clincher Wednesday, are right there in the numbers. The Rangers won all three games here without ever trailing. They were outhit in the series, 47–38, but won because they outhomered the Diamondbacks, 8–3, including three from MVP Corey Seager. They homered in 16 straight postseason games, a record. After losing the final game of the regular season, 1–0, at Seattle to downgrade from AL West champion to fifth seed, they went an unprecedented and unfathomable 11–0 on the road in the postseason. They were insurmountable, forging an 11–0 record when they scored first.

All that reads like the Catalogue of Ships in The Iliad. It does the accounting well enough, but not the humanities of what happened. That’s why a son’s tears tell you more about one of the most improbable World Series champions ever crowned, considering Texas lost the most games in the AL over the previous two years. It’s about the people, not the trail of numbers they left behind.

Get SI’s Texas Rangers World Series Commemorative Issue

Marcus Semien, 33, is a baseball stoic. He has the perpetual mien of a man in deep concentration and a honey-dipped voice that is set at such a low volume sometimes you want to lean in toward him. He smolders with a sense of purpose that can seem palpable. It’s why grown men follow him, not because he tells them to but because they get caught in the vortex of his powerful will.

Such quiet intensity serves him well. He has missed only one game in three years. Damien says Marcus learned such stubbornness from former White Sox teammate Alexei Ramírez, who insisted any day spent out of the lineup was an invitation for someone to take your job. When Marcus came to bat in the ninth inning of Game 5 in a 3–0 sweatbox of a game, it was his 835th turn at bat this year. No player in the history of the game took more plate appearances in a year.

Damien reached out for Tracy’s hand and squeezed it.

“This is it,” Damien said. “Last at bat of the World Series. He’s going to do it. He’s going to do it. I know it.”

Arizona pitcher Paul Sewald threw a sweeper. Marcus fouled it off. The next pitch was a high fastball. Marcus crushed it into the left field seats. Now it was 5–0, and the championship was inevitable. The stoic let out a whoop, threw his head back and danced a bit of a jig as he rounded first base. Damien leaped into the air.

“I almost jumped through the stadium,” he says. “That’s unbelievable. He came to the plate more than any player in history and the last time he does it he hits a home run in the World Series–clinching game.”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

The people. In a game with tablets in the dugouts, wireless communication devices in caps, laminated scouting reports in back pockets and scoreboards that spit out instant readouts of induced vertical break of pitches down to the 10th of an inch, the secret sauce of the Rangers is found in the people recruited by Chris Young, the Texas general manager.

Young pulled Bruce Bochy, 68, off his recliner in Nashville to manage after a three-year hiatus. He convinced Mike Maddux, 62, to be his pitching coach and give his quest for a World Series ring a 42nd try. He hired Dayton Moore, 56, as his front-office consigliere. He signed Game 5 starter Nathan Eovaldi, 33, after a breakfast meeting with his friend and fellow Princeton alum Will Venable last September, in which Venable, then a Boston coach, raved about Eovaldi’s leadership qualities. He hired Venable, too, to be a coach.

It helped that owner Ray Davis kept giving him money to spend. The Rangers spent $889.9 million on free agents the past two offseasons. The run of adding the right people began when Young signed Marcus Semien and Seager as free agents for a combined $500 million after a 102-loss season in 2021.

“We’ve done a lot of background work on everybody we’ve signed and we know what they’re about as people and as competitors,” Young said before this year began.

Young wanted a baseball team with an old soul, a player-centric band of brothers in an era when data analysts and “high-performance” specialists can outnumber the players and seize much of the physical space of the clubhouse.

“When spring training began,” Young says, “I told all our staff, ‘I don’t want to see you in the clubhouse, the weight room, the lunch room ... nothing, unless you have a very specific work-related reason to be there. It belongs to the players.’ I think I scared a lot of people. That’s how firm I was.”

Watch MLB with Fubo. Start your free trial today.

Young, a former pitcher, is so adamant about keeping the clubhouse as a player sanctuary that only one analyst is permitted at pregame hitters’ and pitchers’ meetings to present information, though many may contribute to that information.

Marcus Semien had never played in the World Series. He grew up in El Cerrito, Calif., in the East Bay, played at Cal, was drafted by the White Sox in 2011 in the sixth round and traded three years later back home to the A’s. He signed a one-year deal with the Blue Jays before hitting the free-agent jackpot with Texas.

“I did, honestly, think the World Series was possible this quickly because I know [Marcus is] going to put in the work to do it,” Damien said. “And he’s a silent leader. He leads by example. Has been from the time he was yea high [he points to his thigh] to now. If they want to see what it takes to win, follow him. His way is, ‘I’m not going to tell you. I’m going to show you.’”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Even with Marcus Semien and Seager last year, the Rangers lost 94 games. Based on their runs scored and allowed, they should have lost nine fewer games. They went 15–35 in one-run games, the worst such record in baseball. Young fired manager Chris Woodward.

“We needed a presence,” Young said.

He called his old manager from the Padres. His timing was perfect. Bochy had just returned from Regensburg, Germany, where he managed the French national team (Bochy was born in France, where his father was a noncommissioned officer in the U.S. Army).

“Being back in the dugout in Regensburg, that’s when I got the itch again,” said Bochy, who left the Giants after the 2019 season as San Francisco took more decision-making out of his hands and leaned on analytics.

Then, one day, Young called. He wanted Bochy to manage the Rangers. Bochy asked about managerial autonomy. Young assured him the club would provide whatever information he needed, but the game decisions belonged to him. Bochy was quickly sold. He signed on, causing his wife, Kim, to wonder, “What is it about your life right now you don’t like?”

Said Bochy: “I’m old-school, but I’m also open-minded. I look at all the [heat] maps and numbers. But when you look at the maps they are always going to lean in one direction. For instance, they’re always going to lean toward lefty-lefty matchup. But as a manager maybe you want your best righthander out there because he’s pitching well.

“Sometimes the answer isn’t on a spreadsheet. Sometimes the so-called old-school guys are more open-minded than they are. They rely so much on the spreadsheet they don’t have as much of ability to adjust on the fly.”

Bochy became the sixth manager to win four World Series titles, the first with more than one club. He adapts. He has closed his World Series clinchers with Brian Wilson in 2010, Sergio Romo in ’12, Madison Bumgarner in ’14 and Josh Sborz this year, a guy with a 5.50 ERA and one career save. Sborz was Bochy’s choice over usual closer José Leclerc because Sborz was throwing well, and Bochy trusted what he was watching.

“He’s just calm,” Rangers pitcher Max Scherzer said about Bochy. “He’s just got a presence about him. It’s just very easy to feed off of. He’s got a unique way of going about it. But that’s why he wins.”

An example of Bochy’s calm, been-there-done-that style: He turned to offensive coordinator Donnie Ecker while Arizona righthander Zac Gallen was throwing a no-hitter through six innings of Game 5 and snapped, “Quit with playing possum. How about a hit here?”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

“The rest of us are using tablets and charts,” marveled D-Backs manager Torey Lovullo, “and Bruce is managing by the scoreboard. I really admire that.”

Gallen took the mound in the seventh with his stuff so sharp, he said, he told himself: “I’m going to throw a no-hitter tonight.”

It ended right there. Seager hit a changeup off the end of his bat, sending the ball squirting into left field for a single. Evan Carter laced a double to right. Mitch Garver pounded a single to center, scoring Seager. It happened so quickly. For six innings, nothing. Eight pitches into the seventh, it was 1–0.

The Rangers had never won a 1–0 game in their postseason history. The first game in Texas history was a 1–0 loss—on a walk-off wild pitch with Ted Williams as manager. Game 5 would not stay 1–0. Three singles and an error pushed the lead to 3–0 before Marcus added his dagger of a two-run homer.

It was only minutes later that Marcus was celebrating on the same field with his parents, his wife, his in-laws, his three sons and his infant daughter.

“They mean everything to me,” he says. “This is why I play this game. I show up to win the World Series and to play for them. I want them to have a better life than me.”

During the week Marcus reserved seven rooms at the team hotel for family and friends, prompting teammate Nathaniel Lowe to crack that even with his supersized salary, “You’re playing for free” in the postseason.

“There are just so many emotions from joy to making sure he’s O.K., making sure he’s not overwhelmed with anything,” Damien says. “We all try to do our part just so he can focus on baseball.

“I mean, there are so many emotions I’m going through right now, it’s just ... it’s surreal. That’s the only way I can describe it.”

Damien pointed to the pitcher’s mound, where Marcus’s three sons were jumping and playing on the dirt where Eovaldi somehow allowed nine baserunners and let none of them score. In pitching so gallantly, Eovaldi became the first pitcher to win five starts in one postseason.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

“It was surreal,” Damien said, “actually watching Marcus, like I’m looking at his three kids right now, my grandboys, remembering when Marcus was that age. He’s been dreaming of this moment since he was their age. And then to end it with a home run? I can’t describe how special that is—as a father to see your son’s dream come true. And to do it in front of his kids.

“That’s what got me. It is surreal.”

It really did happen. The Rangers won the World Series in their 63rd season. It was the seventh-longest drought in World Series history. They finally won it in epic style: by spending a boatload of money and identifying the right people to lead them, such as Marcus Semien, Seager and Bochy. The common thread is Young, who won a ring as a player with the 2015 Royals, who were run by Moore.

Young became only the third person to win the World Series as a player and as a general manager, joining Johnny Murphy (the 1936–39, ’41 and ’43 Yankees as a player; ’69 Mets as GM) and Stan Musial (’42, ’44 and ’46 as a Cardinals player and ’67 as the team’s GM).

“It feels so good,” Marcus Semien says. “I’m happy for the fans. I’m happy for everybody who’s a part of this organization. We’ve set the tone for what we want to be moving forward. There’s a lot of losing from the last two years before this, and we turned it around so quickly.”

At that moment, a call went out for the Rangers to gather near the mound for a team picture. The lowest seed to win the World Series, the only team to go 11–0 on the road in the postseason, a team that won Games 4 and 5 by a combined score of 16–7 after losing Scherzer and cleanup hitter Adolis García to injuries, a team that had more blown saves than recorded saves during the season ... yes, that team won the World Series.

“The first eight games I got over here, this team played unbelievable,” said Scherzer, a trade deadline acquisition. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, this team is going to win the World Series.’ And then the next eight games, I was like, ‘Oh my God, this team, we kind of stink right now.’

“But every team’s got to go through that. We went through our funk and once we got through that funk we started playing some good baseball. And then we just got hot in October, and we just ran the table.”

The proof is right there in that photo. Better still, the proof is there in the people Young gathered and the relentlessness of their cause.