Companies around the world are racing to patent the genetic building blocks of plankton – microscopic ocean life that produces much of the oxygen humans breathe – as a long-awaited United Nations treaty on the high seas aims to limit private control of marine resources.

The treaty, which took effect a week ago, aims to protect biodiversity in international waters and prevent the takeover of marine life, which belongs to everyone.

Among its key concerns are plankton, tiny organisms that drift through the ocean and play a central role in sustaining life on Earth.

The first living organisms to appear on the planet, plankton gave rise to all other forms of life. They play a central role in regulating the Earth’s climate by absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen into the atmosphere.

Despite this, most plankton species remain invisible to the naked eye and are still poorly understood.

Over the past decade, scientists have identified nearly 150 billion new plankton genes.

These discoveries have fuelled growing interest from industry, which hopes to extract molecules that could be used in future medicines.

Almost all patents linked to marine genetic resources are held by companies in the world’s 10 richest countries. Together, those states account for 98 percent of all such patents.

Stronger protection for marine life as landmark law takes hold on high seas

Life beneath the surface

Off France's southern coast near Nice, marine scientists have been working to better understand plankton and protect it.

In Villefranche-sur-Mer, researchers head out to sea aboard a scientific vessel operated by the Institut de la mer de Villefranche (Villefranche Sea Institute).

With the help of the ship’s mechanic, engineer Margaux Gras lowers an ultra-fine net to a depth of almost 80 metres. A winch then hauls it back on to the deck. “This is the phytoplankton net. We collect seawater to retrieve the samples inside the collector,” she says.

Gras then rushes to the onboard laboratory, where she joins research director Lionel Guidi to filter the samples and freeze them in liquid nitrogen. Their DNA will be analysed later, back on land.

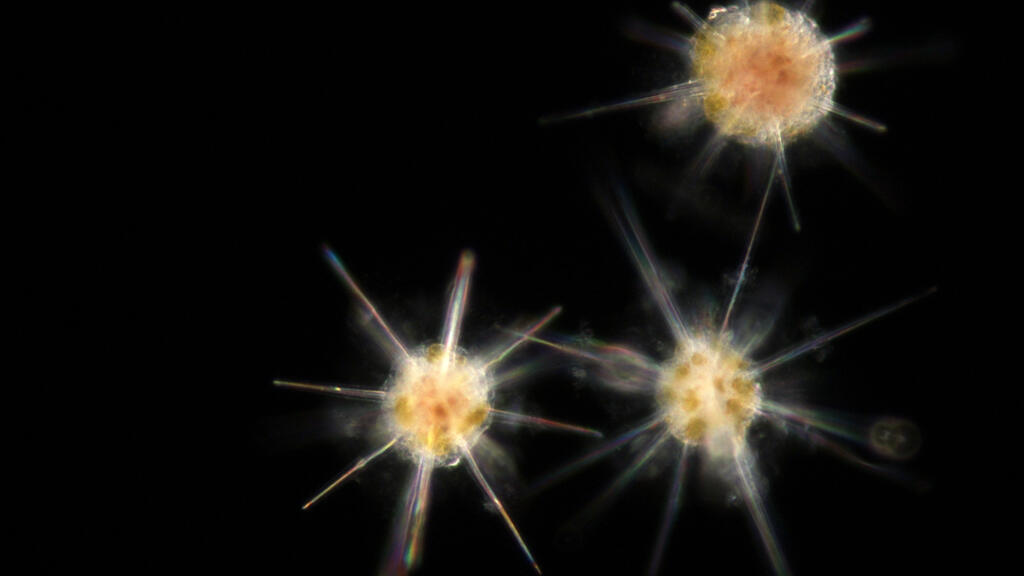

Plankton includes hundreds of thousands of different species. Guidi shows samples of phytoplankton and explains what they contain.

“These are micro-algae smaller than 20 microns, collected with the net we deployed at the back,” he says. “The other net is for zooplankton. These are larger organisms that feed on phytoplankton."

Algae and animals invisible to the naked eye, along with marine bacteria and viruses, plankton form a vast and largely unknown living world.

“A large part of what we don’t know lies in the genes present in these organisms,” Guidi says.

“When we take a sample in the bay, around 50 percent of the genetic signal we detect is unknown. It’s so vast, so diverse and still very poorly understood that there is enormous potential for discovery.”

Indigenous knowledge steers new protections for the high seas

'Marine neocolonialism'

That potential is not just attracting scientists. It is also drawing intense interest from industry, raising concerns about who will benefit from future discoveries.

“Over the past 20 years, there has been a sharp acceleration in the registration of patents linked to marine genes,” according to Vincent Domeizel, an adviser to the United Nations.

“There are now close to 30,000 of them. Half are held by BASF, the German global leader in the chemical industry.”

This concentration of ownership is deeply concerning.

“It means there is a form of predation by the private sector in developed countries, because marine plankton obviously belongs to the whole world,” Domeizel says. “We are seeing a kind of neocolonialism of marine resources.”

Innovations derived from plankton could range from anti-cancer drugs and superfoods to cosmetics and construction materials. Domeizel argues that these advances must benefit everyone.

Niue, the tiny island selling the sea to save it from destruction

Sharing the benefits

That principle lies at the heart of the High Seas Treaty. One of its key goals is to ensure that profits generated from marine genetic resources are shared more fairly.

“The treaty on the high seas aims to share the profits generated by marine genes,” Domeizel says. “This redistribution must be done by financing training and infrastructure in emerging countries.”

He stressed that studying and developing plankton-based innovations requires major investment. “To research, discover and innovate using plankton, you need to fund infrastructure, high-tech equipment and training for young researchers."

Countries that have signed the treaty must now agree on how to apply these measures in practice, a challenge in an already tense geopolitical environment.

This story was adapted from the original version in French by Jeanne Richard.