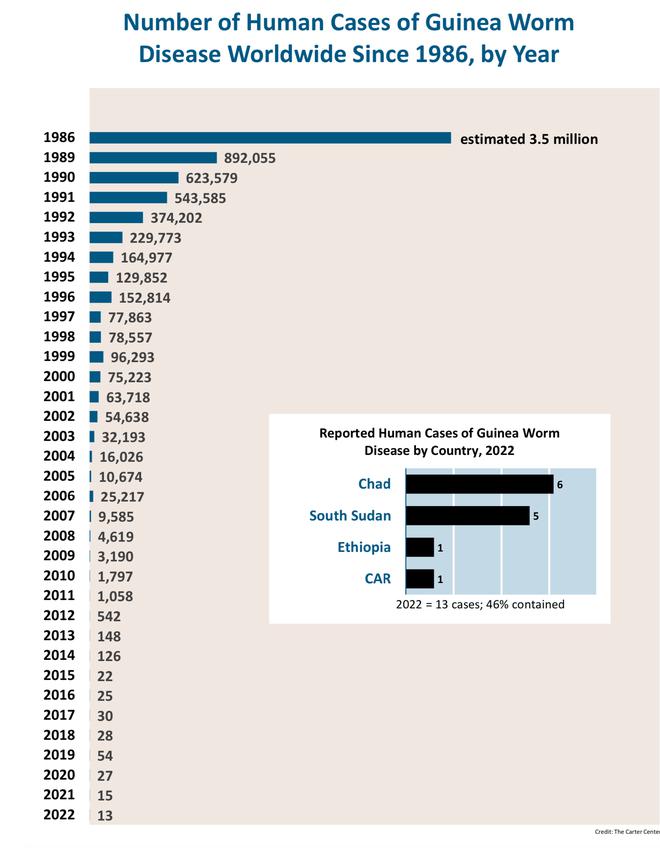

The world is on the brink of a public health triumph as it closes in on eradicating Guinea worm disease. There were more than 3.5 million cases of this disease in the 1980s, but according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) weekly epidemiological report, they dwindled to 14 cases in 2021, 13 in 2022, and just six in 2023.

At a time when medical advancements often headline with breakthrough vaccines and cures, the battle against Guinea worm disease stands out for its reliance on basic public health principles rather than high-tech interventions. Unlike many of its viral counterparts, this parasitic adversary has offered no chance for immunity, defied prevention by vaccines, and resisted most cures – yet the possibility of its eradication is closer than ever thanks to the triumph of human resilience and ingenuity.

“India eliminated Guinea worm disease in the late 1990s, concluding a commendable chapter in the country’s public health history through a rigorous campaign of surveillance, water safety interventions, and community education.”

Rewind to the 1960s, a period marked by two monumental achievements: humankind’s first steps on the moon and the eradication of smallpox. Fast forward to the present, and space exploration has bounded into new frontiers while smallpox remains the lone entry on the list of diseases (of humans) we have managed to banish entirely. This contrast underscores not a failure of medical science but the complex nature of disease eradication.

Infection cycle

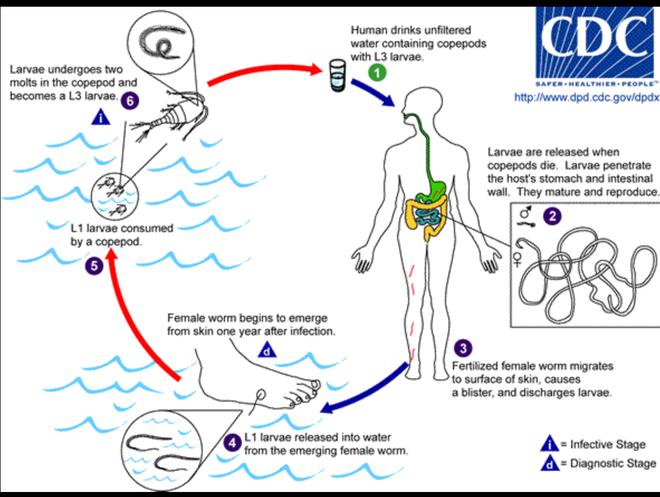

Guinea worm disease, also called dracunculiasis, is the work of the Guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis), whose infamy dates back to biblical times, when it was called the “fiery serpent” and whose presence researchers have confirmed in Egyptian mummies. Individuals whose bodies the worm has entered first experience a painful blister, usually on a lower limb. When seeking relief, they may immerse the affected area in water, which prompts the worm to emerge and release hundreds of thousands of larvae, potentially contaminating communal water sources and perpetuating the infection cycle.

While a Guinea worm by itself is not lethal, it debilitates those whom it infects and prevents them from performing daily tasks and earning their livelihoods.

It manifests as a painful skin lesion as the adult worm — sometimes up to a meter long — emerges. This process, which can last weeks, often begins with a blister and develops into an ulcer from which the worm slowly exits the body. The symptoms typically involve intense pain, swelling, and sometimes secondary bacterial infections at the open wound. Sufferers may experience fever, nausea, and vomiting. The pain can incapacitate individuals, hindering daily activities and work.

Legs most susceptible

More than 90% of Guinea worm infections manifest in the legs and feet. The individual has an excruciating experience when the adult female worm emerges through the skin. The open sore left by its exit is also susceptible to secondary infections. The disease affects people of both sexes. The struggle against Guinea worm disease is symbolic of a broader fight against the diseases of poverty and the self-fulfilling relationship between poverty and illness. The disease thrives in areas where access to clean, safe drinking water is a luxury, and health education and resources are scant.

India eliminated Guinea worm disease in the late 1990s, concluding a commendable chapter in the country’s public health history through a rigorous campaign of surveillance, water safety interventions, and community education. The government of India received Guinea worm disease-free certification status from the WHO in 2000.

This accomplishment was the result of a collaboration between the Indian government, local health workers, and international partners. The strategy hinged on empowering local communities with the knowledge and tools to prevent the disease — including filtering water before use and reporting cases to health authorities for immediate response.

The strategy that brought us to the brink of eradication was straightforward: intersectoral coordination, community participation, and a sustained focus on prevention through health education. Unlike many diseases that have been cornered by medical interventions, Guinea worm disease was and is being pushed to extinction using the fundamentals of public health: ensuring access to clean water (by applying a larvicide called Temephos), spreading awareness through community workers, and meticulously tracking cases and containing outbreaks.

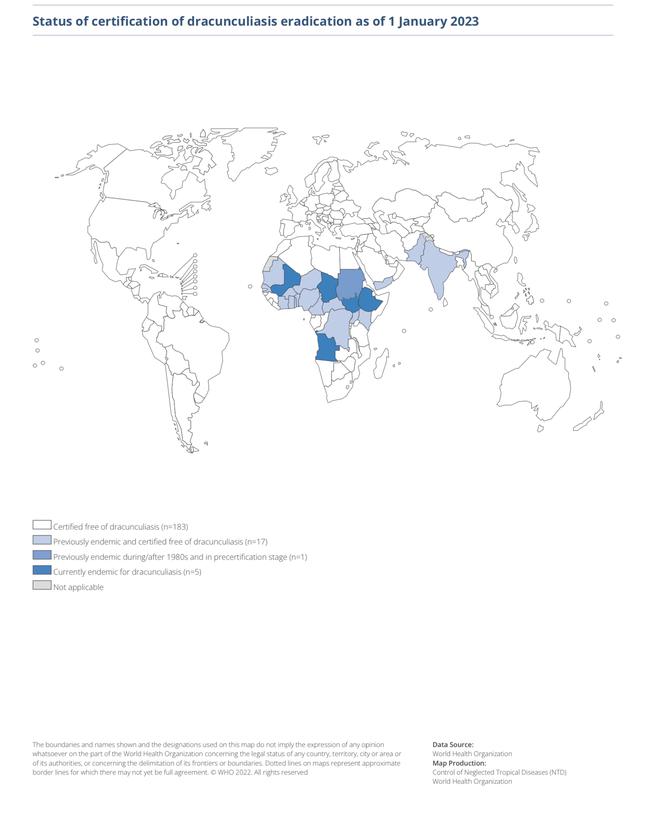

The WHO recorded only six cases of Guinea worm disease in 2023. Nations like South Sudan and Mali, where the disease was once more common, have made commendable progress, although the fight continues particularly in Chad and the Central African Republic, where the last vestiges of this disease cling on.

Eradication

In 2020, researchers also discovered Guinea worms in animal reservoirs, particularly dogs, in Chad, casting a shadow of complexity over the final stages of eradication. This development is a crucial reminder of the disease’s tenacity and, importantly, signals to countries where the disease was previously endemic, including India, to not let their guard down. If the worm persists in this way, governments must stay vigilant and maintain adaptable public health strategies to ensure they don’t lose the upper hand.

This said, the significant progress made towards eradicating Guinea worm disease is also threatened by human and political factors, notably civil unrest and poverty. These challenges are not merely logistical but deeply entrenched in the socio-political fabric of the affected areas, where poverty exacerbates vulnerability to disease and conflict disrupts the basic infrastructure required to sustain public health campaigns. In fact, were such conflicts not in the picture, the global community may have crossed the finish line in the fight against Guinea worm disease a decade sooner. The interplay between health and peace is starkly evident in this context, where the absence of stability and security directly affects the fruits of eradication efforts.

Finally eradicating Guinea worm disease wouldn’t just represent a victory over a single parasitic adversary but a triumph of humankind at large. It will underscore a collective moral responsibility towards the most vulnerable among us, and demonstrate the profound impact addressing health disparities can have on communities. Getting rid of this disease will also be a much-needed testament to what we can achieve when global efforts converge to uplift communities from preventable afflictions.

(Dr. C. Aravinda is an academic and public health physician. aravindaaiimsjr10@hotmail.com)