There are questions to be asked about the “fairness” of the exam system as different grading standards have been used in different UK nations, according to a social mobility expert.

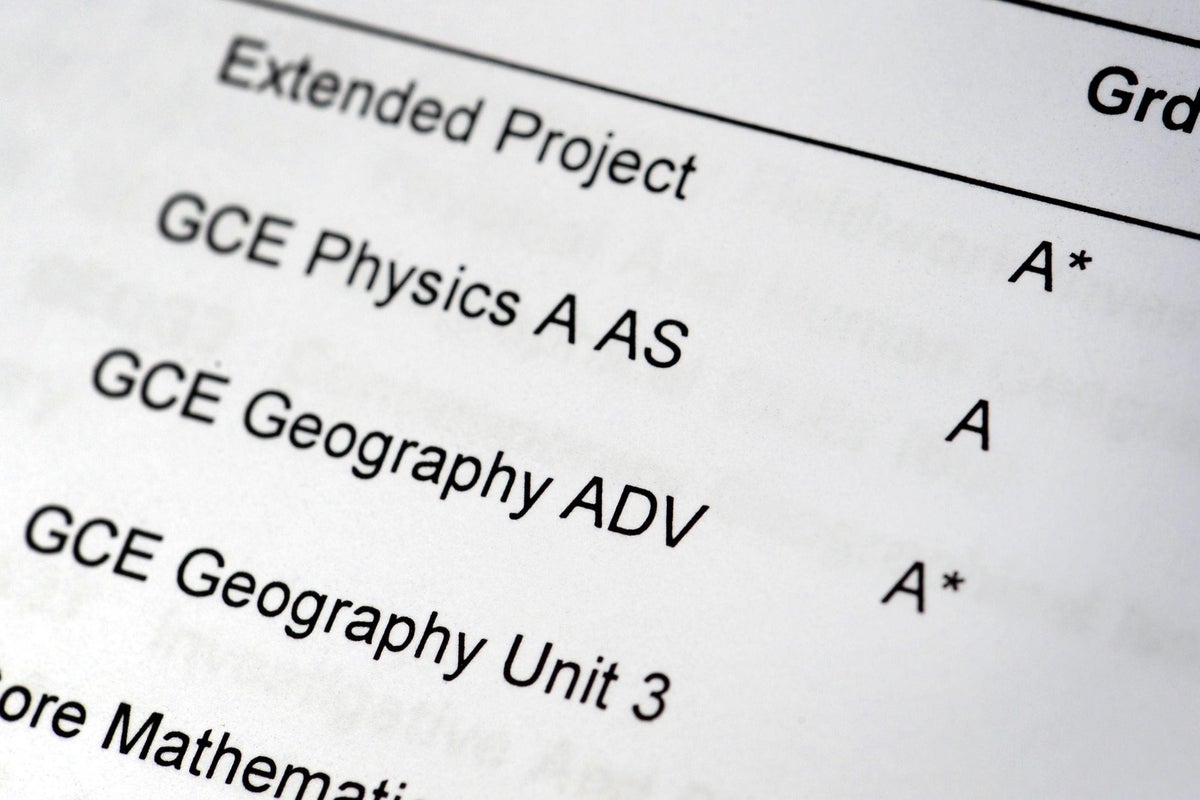

A-level results in England, Wales and Northern Ireland have been published, with each nation taking an individual approach this year to grading and support offered to pupils following changes during the pandemic.

But this has led to warnings from some quarters about the impact on students.

Lee Elliot Major, professor of social mobility at the University of Exeter, said: “Questions must be asked about the fairness of an examination system that has applied different grade standards to different year cohorts of students but also students in the same year – depending on whether they live in England, Scotland or Wales.”

In England, exams regulator Ofqual had said this year’s A-level results would be lower than last year and they would be similar to those in 2019 as part of efforts to return to pre-pandemic grading.

It comes after Covid-19 led to an increase in top grades in 2020 and 2021, with results based on teacher assessments instead of exams.

Many A-level students in Wales and Northern Ireland were given advance information about topics to expect in their exam papers this summer, but pupils in England were not given the same support.

Ofqual previously said it built protection into the grading process in England this year to recognise the disruption that students have faced, which should have enabled a pupil to get the grade they would have received before the pandemic even if the quality of their work is a little bit weaker due to disruption.

Speaking as the results were published, Ofqual chief regulator Jo Saxton said: “I think what’s really important is to remember the context here.

“There have been differences between qualifications across the devolved administrations for as long as there’s been devolution pretty much.

“Again, because we work hand-in-hand with universities and employers, these are well understood.

This is now the time we’ve chosen, and we think it is the right time..., that we return to the normal grading system— Gillian Keegan, Education Secretary

“The number of students who cross borders is fewer than 5% in terms of crossing borders to study at HE and universities are used to working with over 700 qualification types.

“Of course, teachers don’t teach more than one of the qualification types, so again it is well understood by teachers.

“I really, really understand why people are worried that this might be an issue, but I just don’t think that it is.”

Education Secretary Gillian Keegan insisted the way A-levels have been graded in England is fair.

She told BBC Breakfast: “At some point you have to sit exams in life, they usually come to all of us.

“Clearly when it was their GCSEs, it was right in the middle of the pandemic, they all got teacher-assessed grades. This is now the time we’ve chosen, and we think it is the right time – it is two years after the pandemic – that we return to the normal grading system.”

The A-level results show that in England, 26.5% of entries were awarded an A or A* grade this summer, compared to 35.9% last year and 25.2% in 2019.

In Wales, 34.0% of entries were awarded an A or A* grade this year, compared to 40.9% last year and 26.5% in 2019.

Meanwhile, in Northern Ireland 37.5% of entries were awarded the top grades, compared to 44.0% last year and 29.4% in 2019.

The cohort of students who are receiving their A-level results did not sit GCSE exams and were awarded teacher-assessed grades amid the pandemic.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said university admissions service Ucas is used to dealing with different education systems – for example AS-levels operate differently in Wales and Northern Ireland than in England.

He said those using their A-level results to apply to university “should not be worried” as Ucas understands the differences in qualifications.

Asked if English A-level students could be at a greater disadvantage when applying to university than students in Wales and Northern Ireland, Clare Marchant, chief executive of Ucas, said: “No, because what’s happened is of course, all those grading arrangements were known since way back in the autumn last year, so autumn 2022 when each of the nations said what the grading arrangements were going to be, so universities and colleges when they were making offers in the spring this year, knew what the grading arrangements were.

“Universities and colleges across the UK take hundreds of different qualifications each year, both UK qualifications and international qualifications they’re used to dealing with different qualifications with different levels of value and all of that, so it’s absolutely not a problem universities and colleges are used to it.”