The rapid evolution of cicadas' flight ability may have been spurred by the emergence of predatory birds, new research suggests.

These insects' bodies and wing shapes changed dramatically over the course of 160 million years, at the same time birds began to dominate the skies as aerial predators, according to the research, published Friday (Oct. 25) in the journal Science Advances.

The study analyzed changes in giant cicadas in the Dunstaniidae and Palaeontinidae families during the Mesozoic era (252 million to 66 million years ago). They found that cicadas in the early Cretaceous may have become 39% faster — and had 19% more flight muscle mass — than their ancestors in the late Jurassic, 60 million years before.

The research suggests predation by birds drove this rapid development in an evolutionary "air race," culminating in cicadas that more closely resembled modern species.

Overall, the research aimed to shed light on the evolution of wings. Wings have evolved independently four times: in insects, flying reptiles called pterosaurs, birds and other dinosaurs with wings, and bats. But the evolution of these traits is hard to study. Wings often don't fossilize well, and "to calculate the flight ability of extinct insects is really challenging," Chunpeng Xu, a paleontologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology and lead author of the study, told Live Science in an email.

But ancient giant cicadas offer a solution. There are over 80 well-documented giant cicada species in the fossil record over the late Mesozoic. Their large, well-preserved wings — some of which span nearly 6 inches (15 centimeters) — make them perfect for studying wing evolution.

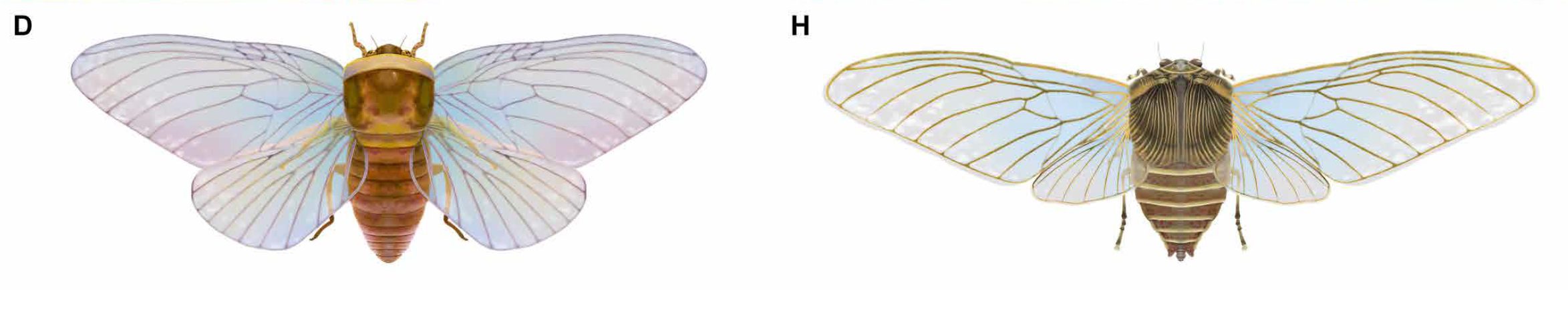

For the new research, the team analyzed each species, mapping 300 data points on the wing to track changes over time. They concluded that the giant cicadas' body and wing shape evolved to help them become faster and more efficient flyers. Longer, slimmer wings and an increase in flight muscle mass over 60 million years helped the cicadas soar faster, the researchers said.

Related: Are birds dinosaurs?

But this evolution had to be driven by some outside force. "Most species of early birds probably fed regularly, or even exclusively, on insects," Xu said. "They were as small as sparrows, with short, toothed jaws and wide gaping mouths that were well suited for catching insects in the trees."

The emergence of birds that could catch insects midflight around 150 million years ago could have caused cicadas to rapidly evolve adaptations to outmaneuver their new predators, the research suggests.

The work is "very, very cool," Michael Habib, a paleobiologist at UCLA who was not affiliated with the study, told Live Science. But he cautioned that, although the research on increased flight speed is strong, he's less convinced that the cicadas also became more maneuverable. "Fast things tend not to be as good at making sharp turns," he noted.

However, Habib praised the authors' attempts at such complex calculations. "Modeling aerodynamics of fossil animals is hard," he said. "It requires that you really, really understand the relationships between the materials, the anatomy and the flow of these animals … And that has a lot of utility in things like robotics."