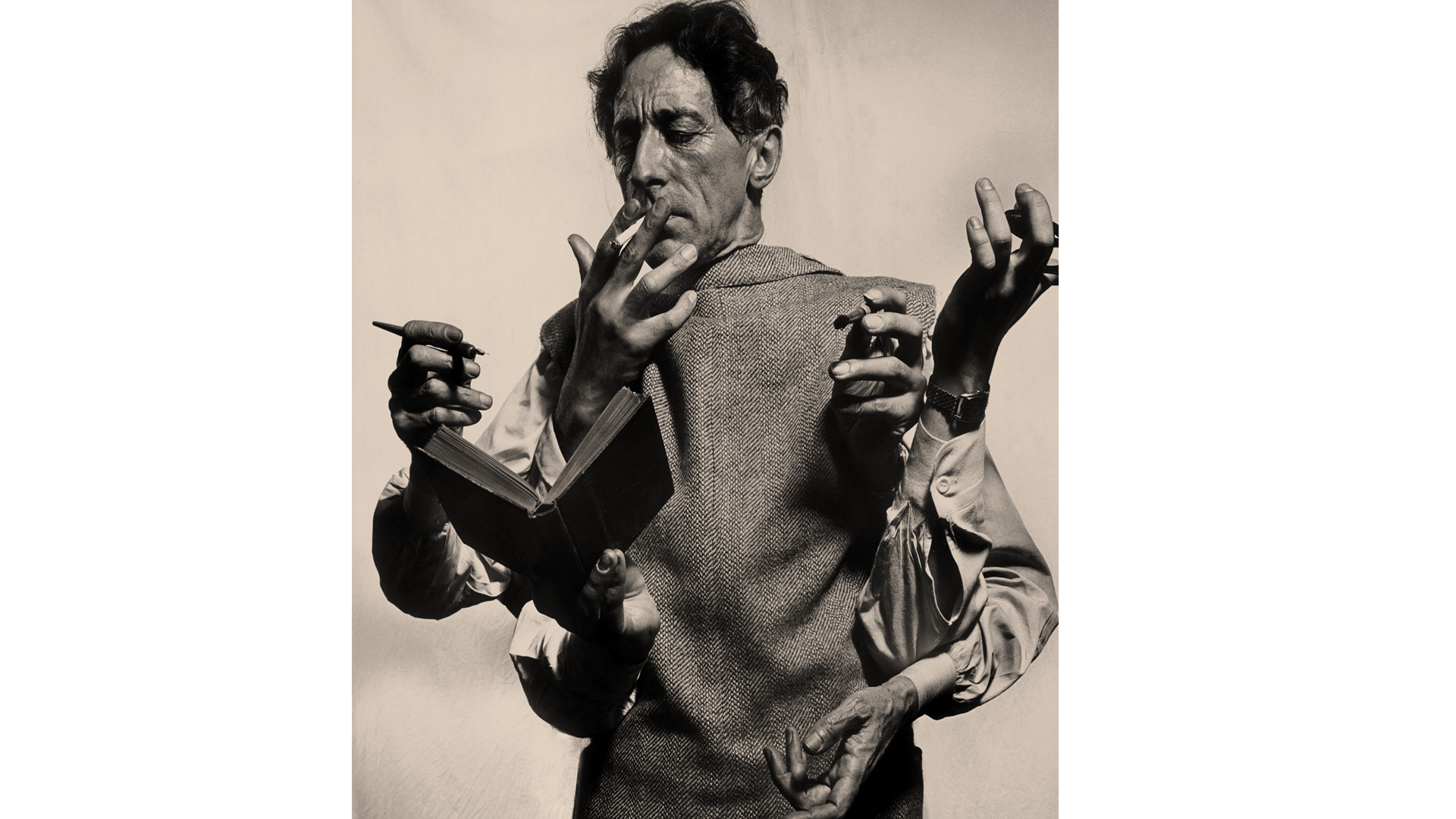

Artist, poet, novelist, playwright, film-maker – Jean Cocteau was all of them and more. Perhaps, though, it was the poet’s dreamy nature that defined him, his unbounded approach to art forever propelling Cocteau towards the fringes of the modernist movement. Yet, he was at the heart of it, and it was Cocteau who invited Picasso to create the sets and costumes for his ballet, Parade, created with Erik Satie for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in 1917.

‘Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge’

This staging of Italy’s most extensive retrospective of Cocteau, ‘Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge’, a carnival of 150 works, including drawings, posters, an incredible array of jewellery, tapestries and film excerpts, is a tender dedication. For it was with a collection of Cocteau’s drawings and furniture designs that Peggy Guggenheim launched her inaugural exhibition and career as a gallerist, at Guggenheim Jeune, London, in 1938.

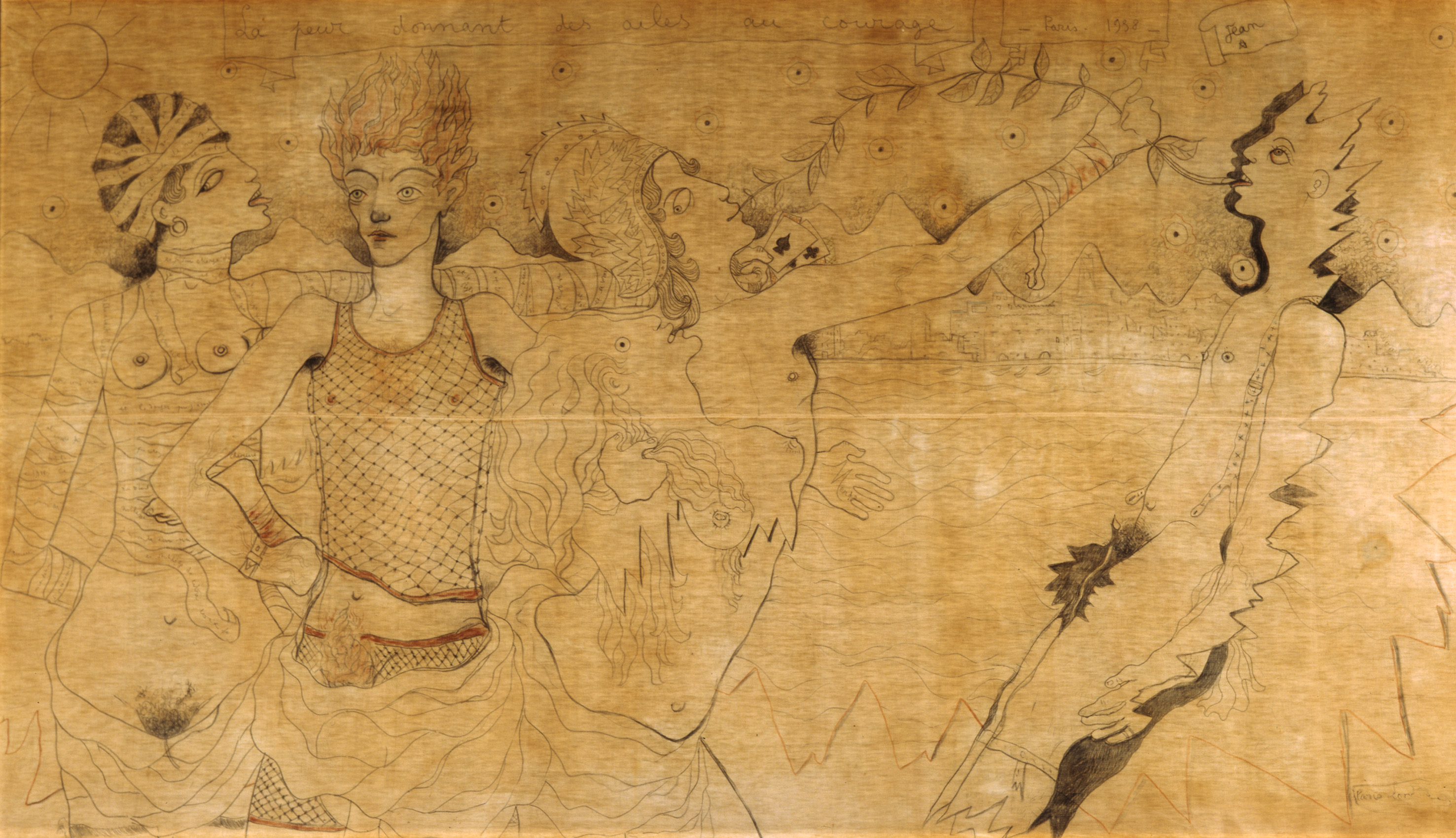

The show caused an uproar with British customs because, as Guggenheim later recounted, ‘One [of the works was] an allegorical subject called La peur donnant ailes au Courage, which included a portrait of the actor Jean Marais. He and two decadent-looking figures appeared with pubic hairs.' Painted by Cocteau on a cotton sheet, this erotic tableau – Marais had become his lover the year before – is a star exhibit in an entire gallery of them.

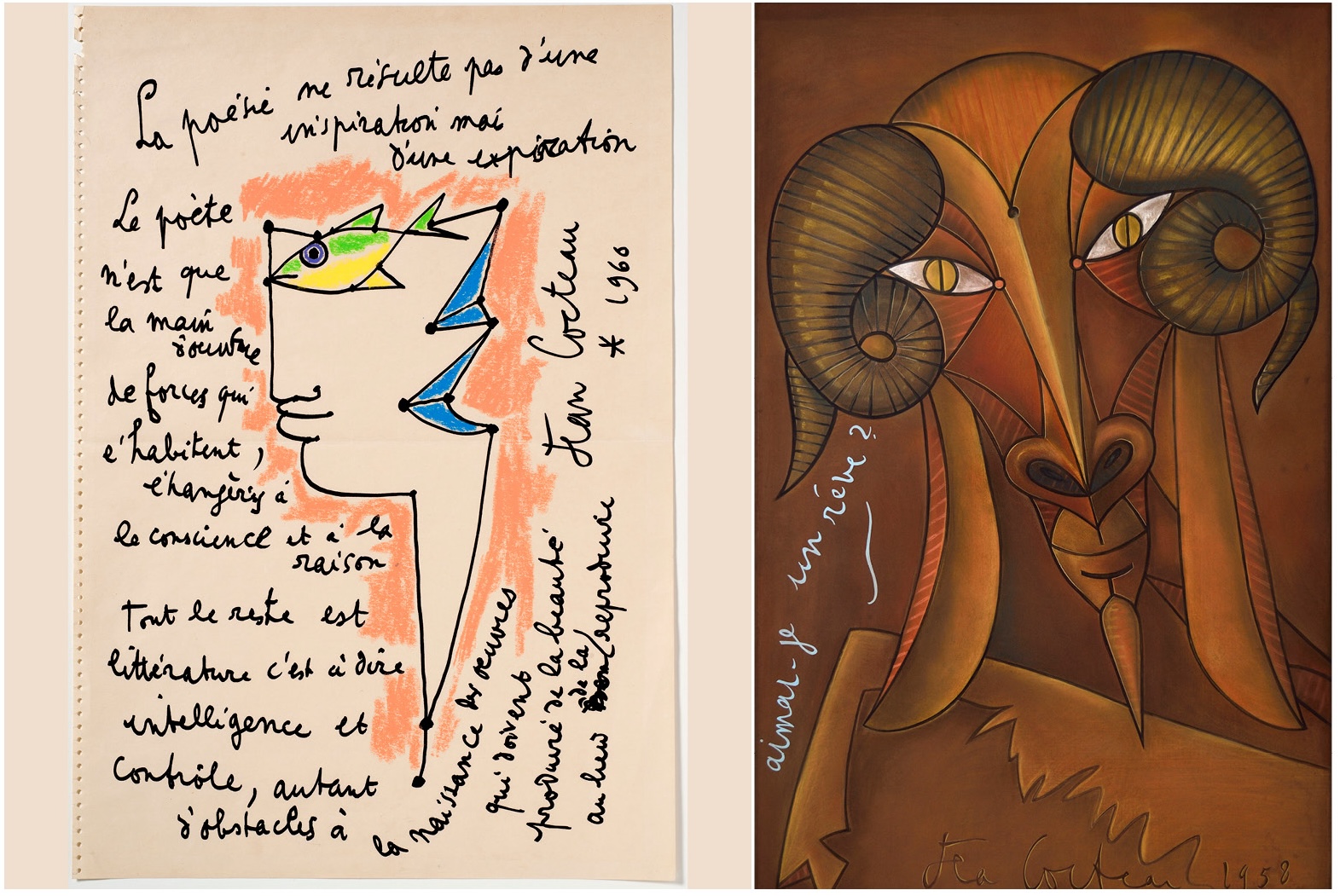

The galleries are carefully defined, all the better to comprehend the scintillating scope of Cocteau's artistic output. As such, the order offers fresh insight. The collection of Cocteau's authored books, for instance, shines a light on lesser-known titles The Infernal Machine, The Difficulty of Being, and Profil-Opium. It also allows an overview of his book, magazine and poster design, and Cocteau's incisive approach to each medium

Then there's the jewellery design, which occupies the entire Gallery 10, and where we see Cocteau's recurring classical motifs rendered in gold, enamel and precious stones. A plastic, metal and faux pearl 'eye' brooch designed for Schiaparelli, however, is a highlight.

The exhibition also allows a rare opportunity to see the exquisite gold, silver and gem-set sword the Maisons-Laffitte-born artist designed for Cartier. Cocteau, whose film-making career flourished later in life, was invited to design the ‘Academician Sword for Jean Cocteau’ with its divine lyre, star and Orpheus outline, in 1955, when he was afforded membership to the Académie Française.

While this show is a passionately assembled love letter to a 20th-century cultural great, the clumsy ‘juggler’ label doesn’t do much to dispel the myth of the artist as the handyman creative. Nor does the exhibition organiser Kenneth E Silver’s argument for Cocteau as ‘a model for the kind of wide-ranging cultural fluidity we now expect of contemporary artists’ convince, considering Picasso, a close friend of Cocteau, also designed ceramics and jewellery.

So, let’s leave the last word to WH Auden: ‘The lasting feeling that his work leaves is one of happiness; not, of course, in the sense that it excludes suffering, but because, in it, nothing is rejected, resented, or regretted. Happiness is a surer sign of wisdom than we are apt to think, and perhaps Cocteau has more of it than some others.’

‘Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge’ is at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice until 16 September 2024