The Victorian government this week gave the state’s local councils a gargantuan task: solve the housing crisis by accelerating new housing.

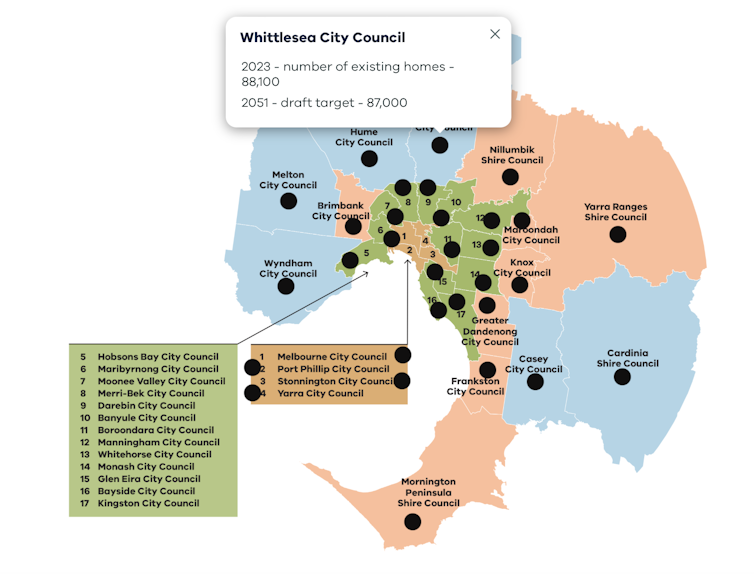

Each council now has a target for new housing to reach by 2051. By that time the state’s population will have grown by over 3 million to top 10 million. While the exact targets aren’t final – they’re out for consultation – the general idea of targets applied to council areas is unlikely to change.

That’s because they’re the local expression of the state’s grand plan to build millions of new homes. Released last September, the plan aims to “tackle the root of the problem: housing supply”. This plan gave us bold numbers without detail as to where the numbers came from.

Now we have indicative local targets, announced through a press release. But there’s again no detail – just maps of each council area and how many more homes the government wants. Councils have already raised concerns about the difficulties of meeting these targets, the strains on local infrastructure and services, and the impacts on the character of neighbourhoods.

What’s remarkable about these targets is that if all councils meet their targets, we would have 40% more houses than we would need to meet projected population growth.

Do we really need so many new homes?

To meet projected population growth, Victoria needs to build 57,000 dwellings a year on average for the next 27 years. But the government’s statement also called for an additional 23,000 dwellings a year on average to make up for a supply backlog from previous decades.

In total, the government wants more than 2.2 million extra dwellings built. As of 2021, Victoria had 2.8 million houses in total.

Why do we need so many more houses? According to the government’s plan: “It’s a simple proposition: build more homes, and they’ll be more affordable.”

Here’s the interesting part. According to the government, the housing shortage is to be fixed primarily through local government policy reforms.

The unstated assumption is councils and their planners are to blame for protecting detached house owners against medium-and-higher-density developments in their backyards.

The plan refers to a backlog of around 1,400 applications for multi-unit housing that have been waiting for a council decision over six months.

What’s the solution? Under the government’s plan, it is:

- fast-tracking medium-density developments that use agreed “deemed to comply” templates (if a proposed development meets a codified standard, it is also deemed to comply with the corresponding objective)

- planning permit exemptions for granny flats

- giving the housing minister the power to approve major well-located higher-density developments, including affordable housing, without council involvement.

This is not the first time a state government has tried to fix housing. Over the past three decades, Victoria and New South Wales have tried a number of similar initiatives. These have had no noticeable impact on housing affordability or long-term supply.

The impact of planning on housing supply is overstated. A far more pressing problem is interest rates and incentives to treat housing as an investment rather than a home. Negative gearing and capital gains tax discounts for landlords have only made things worse.

In reality, developers are sitting on a large pile of medium-density developments approved by councils but where construction has not begun. In the last quarter of 2023, builders were shelving more apartments and townhouses than they were starting to build.

The elephant in the room

Rising interest rates have pushed Melbourne house prices down 20% (adjusted for inflation), back to pre-COVID levels. There are also fewer new dwellings starting construction.

It’s very hard to see why private developers would crank up supply by 40% when faced with falling prices. If prices fall, there’s less incentive for developers to build more. And if many more houses are built than there is demand, prices will fall even more sharply.

While the rental market is exceptionally tight, this is largely due to student-driven migration, which surged in mid-2022, around the same time the Reserve Bank started to lift interest rates. In 2023, net overseas migration into Victora was 154,000 (29% of the nation’s total), of which half were students.

This problem is best resolved by federal government policies, such as the proposed cap on international students, rather than local government planning reform.

New movements such as YIMBY Melbourne pin the blame on councils, just as the state government is doing. In April, Premier Jacinta Allan suggested councils that fail to meet their targets could be stripped of their planning powers. Councils such as Booroondara have pushed back, claiming the housing crisis is the result of “poor planning policy by Commonwealth and state governments over many years.”

Over the 30 years to 2021, Melbourne’s 15 main inner and middle-ring municipalities increased housing by 55%, or 318,000 dwellings. Of these, 90% were of medium and higher densities, according to my analysis of census data. Detached housing in these areas has fallen from 66% to barely 50% over that period. If the government’s targets were met, detached houses would be under 33%.

The City of Melbourne itself has grown tremendously. From a permanent population of near zero in the 1980s, it now has more than 88,000 high-density dwellings and a population of more than 150,000. The northern part of the city now has a population density of 38,400 per square kilometre, double that of Hong Kong. Under the government’s plan, the CBD would more than double housing stock again, rising by 122%.

If councils are forced to approve more and more developments with no guarantee they will even be started, it is likely planning standards will drop.

The state government would be better served by choosing less ambitious targets and focusing less on councils and more on its own abilities.

After all, the largest housing crisis is in social and affordable housing.

This is a lever the state government can directly control. In 2020, it began its Big Housing Build, a one-off policy which has 9,200 social and affordable homes built or under construction. If this policy was made permanent, we could expand social and affordable housing through direct investment – and help the people hurting most from overly expensive housing.

David Hayward does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.