Plantation slavery may have originated on a tiny west African island at the equator, according to archaeologists who investigated a 16th-century sugar mill and estate.

São Tomé (Portuguese for "Saint Thomas"), an island 150 miles (240 kilometers) west of Gabon in the Gulf of Guinea, was first settled by the Portuguese in the late 15th century. Finding an uninhabited island with abundant wood, fresh water and the potential for growing sugarcane, the Portuguese monarchy tried to entice people to move there. Due to high rates of malaria, though, São Tomé was thought of as a death trap. By 1495, to supply labor for the sugar trade, the Portuguese rulers forced convicts, Jewish children and enslaved Africans to move to the island.

While other Portuguese sugar mills relied on enslaved people solely for manual labor, in the São Tomé sugar plantation system, enslaved people — largely from what are now Benin, the Republic of the Congo, Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo — performed nearly all the tasks, from the harvesting and processing of sugarcane to the carpentry and stone masonry needed to build and run the mills.

This made São Tomé "the first plantation economy in the tropics based on sugar monoculture and slave labour, a model exported to the New World where it developed and expanded," the researchers wrote in a new study, published Monday (Aug. 14) in the journal Antiquity.

The island's plantations were so successful that in the 1530s, São Tomé surpassed Madeira — an Atlantic archipelago that the Portuguese used for their lucrative sugar operations — in supplying the European markets with sugar, and dozens of sugar mills were built.

In the new study, researchers — led by M. Dores Cruz, a historical anthropologist in the Department of African Studies at the University of Cologne in Germany, along with colleagues from the University of São Tomé e Príncipe (USTP) — investigated Praia Melão, a newly identified estate on the island's northeastern coast that is the first of São Tomé's sugar mills to be analyzed with modern archaeological methods.

Looking at the Praia Melão sugar mill

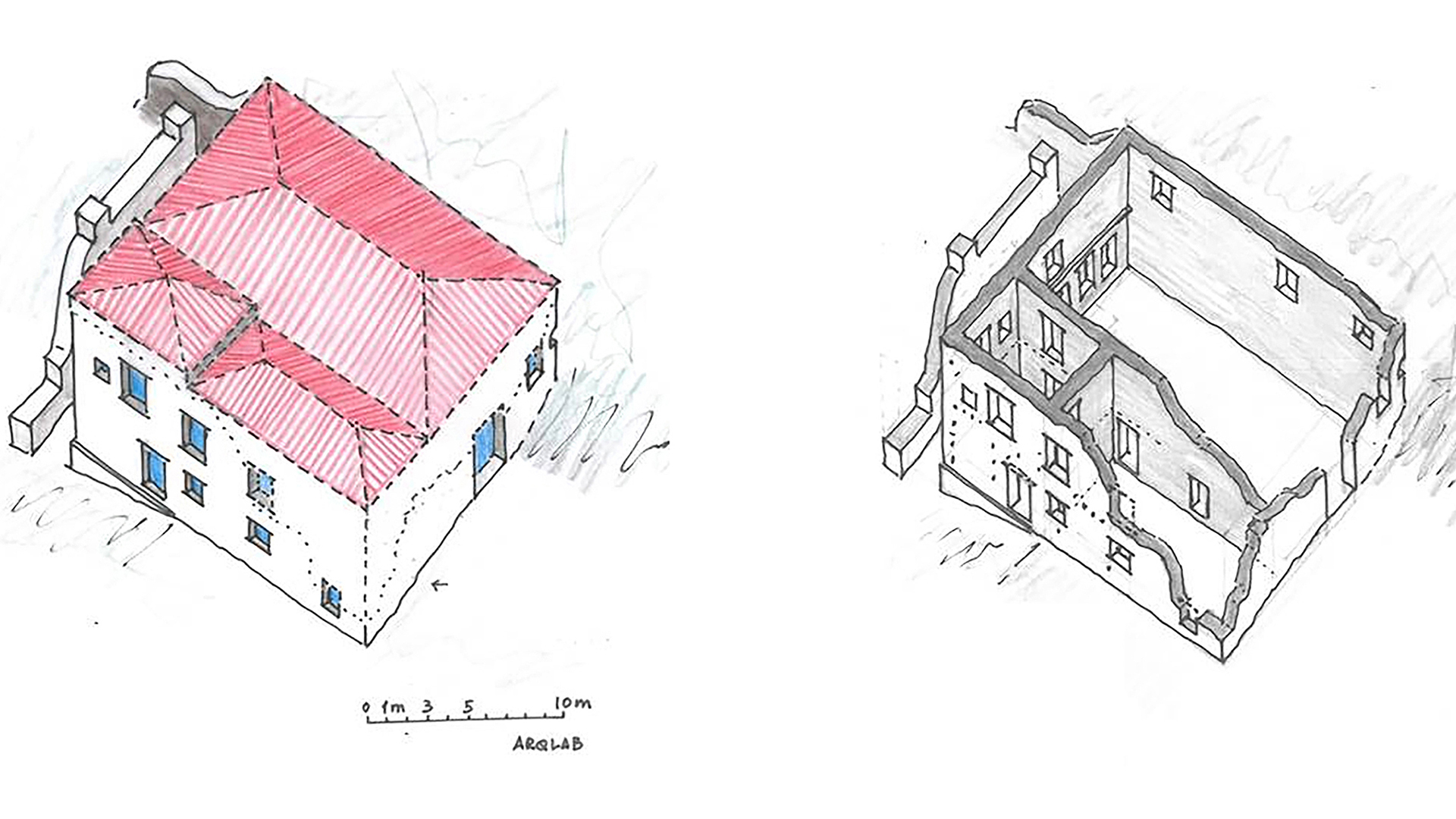

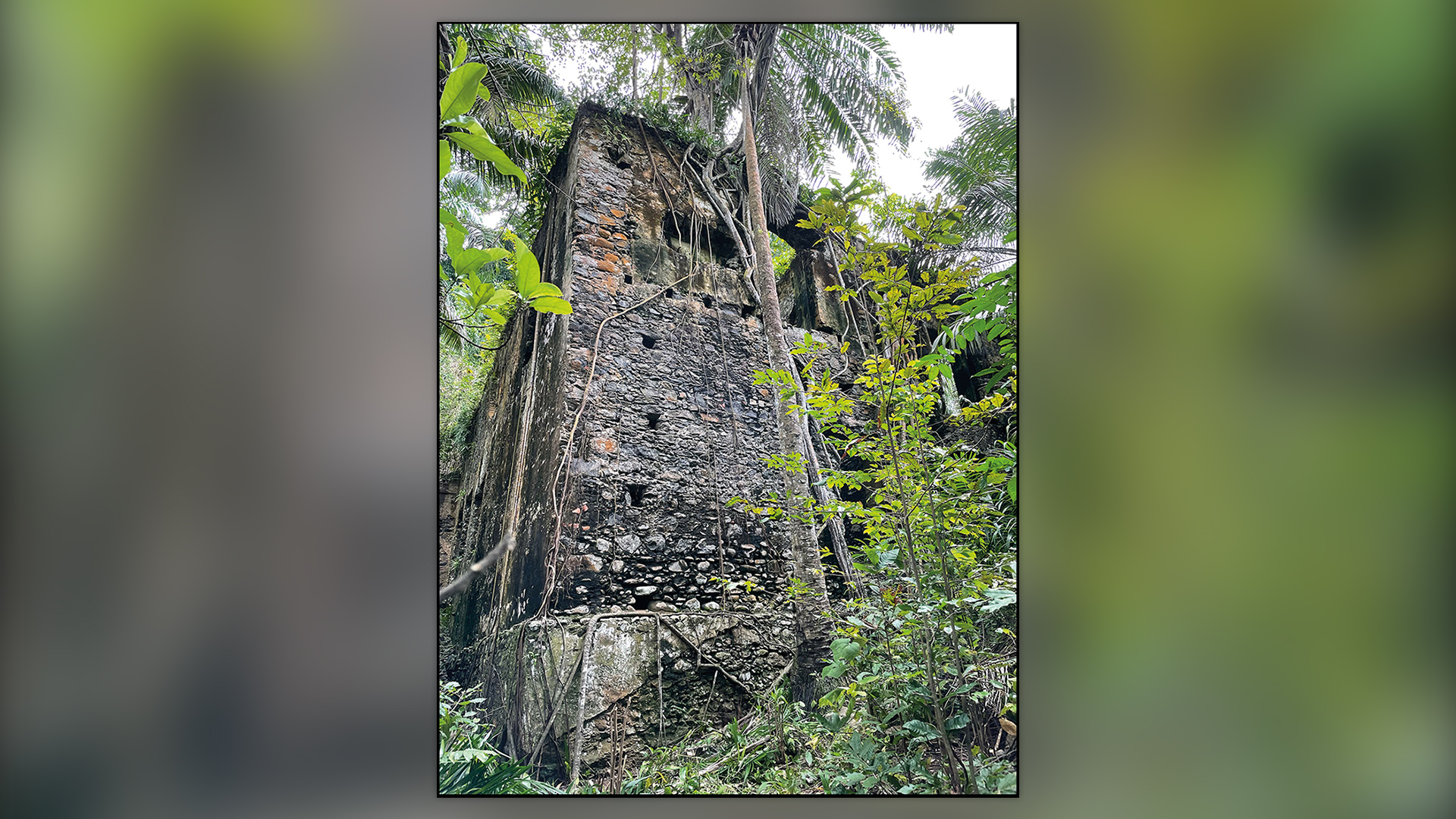

The sugar mill at Praia Melão includes a large stone building that was refurbished and expanded over the span of 400 years. Featuring a now-collapsed clay roof common in Portuguese buildings of the 16th century, the building is two stories tall. Domestic quarters were located on the top floor, while the graffiti-covered lower floor included a sugar boiling room. The archaeologists also discovered numerous fragments of ceramic sugar molds similar to those used in Madeira.

"Sugar production was a very complex process," Cruz told Live Science in an email, and it "was not packed in bags and loose as today." First, cane syrup was boiled and in large copper cauldrons until crystals formed. Next, the sugar was put into cone-shaped ceramic molds, which allowed molasses to drain out and the sugar crystals to dry and harden. The resulting sugar cone was called pão de açúcar — Portuguese for "sugar loaf."

But São Tomé struggled to keep up with the demand for sugar, given the high humidity, fast-growing forests and slave rebellions. So the Portuguese moved many of their operations to Brazil in the early 17th century, taking the plantation operating model with them. Mills on São Tomé were reused or fell into disrepair by the 19th century.

"Archaeologically speaking, Sao Tome is uncharted territory," Marco Meniketti, an archaeologist at San José State University in California who was not affiliated with the project, told Live Science in an email. "Investigation of the Sao Tome sites may be the most important new development in years for scholarship of the sugar and slave connection," he said, providing new information on an industry primarily known from 17th-century records from Brazil and the West Indies.

Cruz hopes they will be able to find more sugar mills or the enslaved-African quarters in the future, but her attention is still focused on Praia Melão.

"The building is in very bad shape, with cracks on the walls and walls bulging, and it is also covered by vegetation," she said, so she is currently searching for funding to preserve the site.

"There are no archaeologists in São Tomé," Cruz said, but USTP is launching a new master's program in history and heritage this fall, with the aim of training people in conservation and preservation of the island's important archaeological sites.

"The opportunity to investigate these unstudied sites should not be lost," Meniketti said, as "this archaeologically rich environment can significantly inform us about the intersection of slavery and capitalism."