Back in the 1980s there were just ten or so pink pigeons left in the wild. Known to scientists as Nesoenas mayeri, the species is found only on Mauritius, the Indian Ocean island that was once home to the dodo. Like the dodo, the pink pigeon made an easy target for cats, rats and other predators introduced by humans, who also chopped down almost all of their native forest. Unlike the dodo, however, the pink pigeon has since made a remarkable recovery.

Fortunately, the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation had already taken 12 birds from the wild in the 1970s and 80s to establish a captive population. The offspring of these birds were then released during the 1990s and early 2000s and there are now at least 400 living in the wild. The species has even been officially down-listed twice, from “critically endangered” to “vulnerable”.

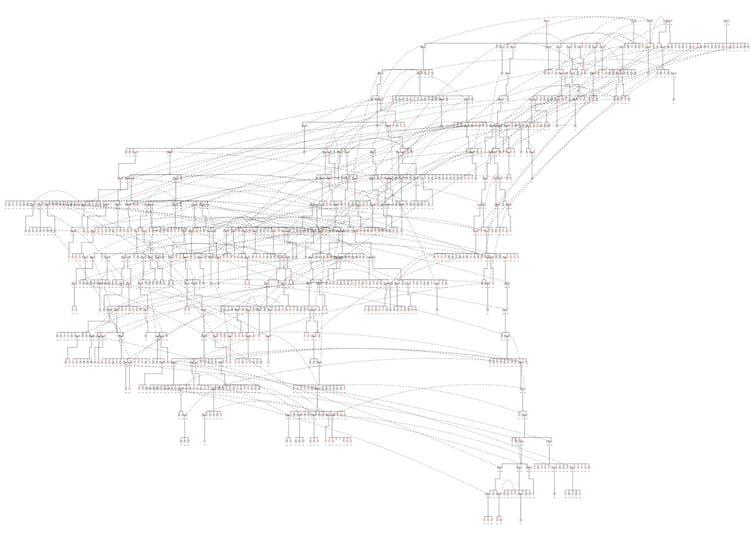

However, such a severe population bottleneck can lead to significant “genomic erosion”, where a species becomes less genetically healthy as so many animals are closely related. To examine the exact impact, we worked with a team of scientists to sequence the DNA of 175 birds sampled between 1993 to 2010 during the period of population recovery. Our results are now published in the journal Conservation Biology. Disappointingly, we found that the species continued to lose genetic diversity even as overall numbers increased during the successful conservation rescue programme. We speculated that the bottleneck must have changed something in the pink pigeon’s DNA.

To understand what caused this continued genetic erosion, we looked at data on 1,112 pink pigeons in European and US zoos. This data had been collected over four decades, and included each bird’s level of reproductive success and longevity together with levels of inbreeding calculated using pedigrees. Based on the relationship between these factors, we found the species carried a worryingly high “genetic load”.

The genetic load basically consists of many recessive harmful mutations that have the potential to reduce an animal’s ability to reproduce. This could be seen, for example, in a reduced number of eggs that hatch, or the number of young that successfully fledge the nest. Before the pink pigeon bottleneck, the effects of these mutations were masked since there were plenty of healthy genetic variants around to offset the harmful ones. However, small populations are much more vulnerable to random fluctuations in genetic composition, making it possible for the harmful mutations to have an effect.

Inbreeding can also cause such mutations to become more harmful, if the offspring of two related individuals inherit the same harmful mutation. When that happens, the healthy genetic variant no longer masks the harmful effect of the mutation and the individual may fail to hatch or fledge the nest. We believe that this caused the continued genetic erosion of the pink pigeon in the wild.

Ultimately, all 480 or so free-living birds are somewhat related to the ten that managed to survive in the wild in the 1980s, and to the 12 that were used to establish the captive-bred population. This has resulted in slow, prolonged inbreeding. In turn, this meant the pigeons had less success hatching eggs and fledging, and didn’t live as long.

Since only the fittest pigeons were likely to hatch, fledge and reproduce, there were fewer birds effectively contributing to the next generation (and genetic variation was lost), even as their overall numbers increased. Consequently, the population continued to lose genetic variation despite growing in size.

What we have learned from this study is that in order for the pink pigeon to avoid extinction, we will need to reintroduce the offspring of birds bred in Jersey Zoo and other EU zoos. These pink pigeons harbour genetic diversity that has since been lost from Mauritius, and reintroducing them would reduce the level of relatedness on the island.

Our study also shows that conservation can’t simply stop after a population seems to have recovered in numbers. We believe that genomic analyses are needed to truly evaluate the conservation needs of a species and its recovery potential. This cannot only be done by analysing population numbers. The data generated by the Earth Biogenome Project is going to be instrumental in identifying species most at risk of extinction. The project aims to sequence two million or so species in the next ten years. This data will not only help in our assessment of biodiversity, but must also be used to guide future conservation actions.

Cock Van Oosterhout receives funding from the Royal Society International Collaboration Awards (ICA\R1\201194), and the Earth and Life Systems Alliance (ELSA) at the Norwich Research Park (NRP). Cock Van Oosterhout is affiliated to the Conservation Genetics Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Jim Groombridge does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.