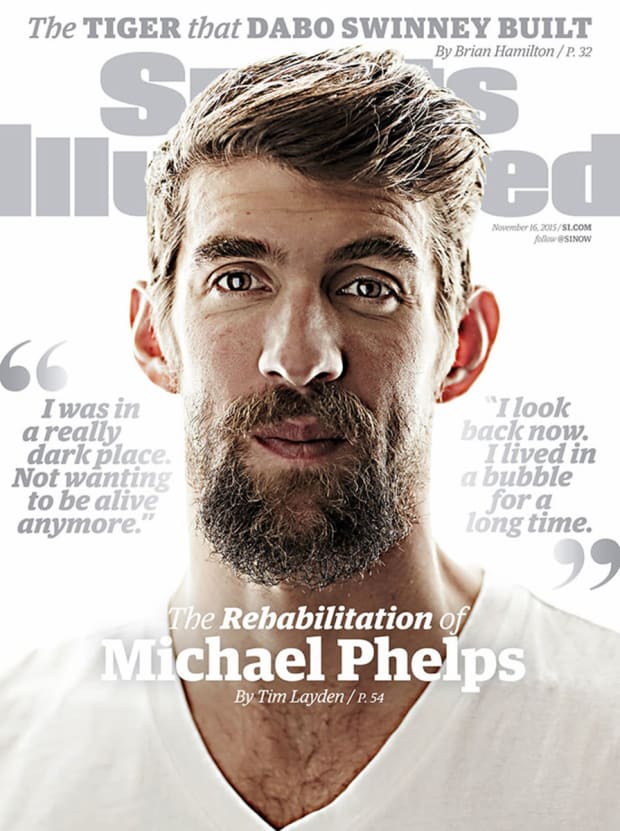

Michael Phelps is so routinely open about his depression and anxiety that it’s hard to remember a before time. But it wasn’t until 2015, when Sports Illustrated writer Tim Layden sat down with the most decorated Olympian of all time, that Phelps started speaking freely about his mental health. He divulged his time in rehab the previous year for alcohol use: “I wound up uncovering a lot of things about myself that I probably knew, but I didn’t want to approach. One of them was that for a long time, I saw myself as the athlete that I was, but not as a human being.” After his second DUI, he said, he hadn’t wanted to be alive anymore.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

These kinds of disclosures happen more frequently now, to the point where they almost seem commonplace; Naomi Osaka’s and Simone Biles’s names are just two of the many that have become shorthand for these monumental stories. Those are exactly the stories Phelps wants to hear. In honor of Monday’s World Mental Health Day, he’s announcing an NFT collection coming soon, with his proceeds going to his Michael Phelps Foundation. In advance of the seven-year anniversary of his groundbreaking cover story (his ninth for SI), Phelps is yet again reflecting—on that cover, on himself and his mental health, and on advocating for industry-wide change.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Sports Illustrated: We’re about two and a half years into a pandemic. How’s your mental health?

Michael Phelps: I look at the pandemic almost as a blessing, because my mental health was severely challenged during it. I had to be aware and make sure that I was taking care of it—and taking care of it daily. I found myself in some pretty low lows. I think my wife and I were able to learn how to communicate more, and I think that was the reason why I was able to get through. There were some very, very, very, scary times. But I look back at it now and I’m thankful that it happened, because now I’m even more prepared or equipped, so you will, if anything like that ever happens again.

SI: Were you feeling suicidal at all?

MP: No. Just dark, just scary. For me, when I get in dark spots, I just feel alone. I know when people have depression that is normal. There are times where I will dive into pretty deep depression, but I think I’ve found different tools to help me when I’m in that state. I journal a lot. Those journal entries are a little weird to look at. But I’m glad I do them on those bad days, because I want to see what my mind was like. I want to see what I’m going through.

SI: What’s your relationship like with swimming these days?

MP: Nonexistent, really. I don’t spend much time in the water. I’m trying to stay fit. If I want to have a workout in the pool, I feel like I’d have to go six or seven thousand yards or meters. That’s what I was doing throughout my career, so I don’t really want to do that anymore.

I would say it’s more of a form of therapy than anything else. I know that if I have a really, really low point and I need something right away to help me get out of it, I can jump in the pool for 20 minutes and get out and feel like a completely different person. There’s just something [about] being in the water for me. It’s very calming. I can kind of shut everything down and just be. I think that’s probably one of the very few places where I’m able to kind of do that. I’m learning to do it in other places, but that’s been something that I’ve known for 30 years.

SI: Why did you pick an NFT collection of your Nov. 16, 2015, cover as your next foray into the mental health space?

MP: It’s fun—being able to have this idea where I have a lot of really, really cool covers and a lot of cool stories that I’ve had in Sports Illustrated. To be able to partner with them to do something like this, for charity, for me it’s just fun. I think the opportunity is something that I thought was really neat, and the space is pretty cool, so it seemed like a no-brainer for me.

SI: What is the significance of the 2015 SI cover for you, that you wanted that in particular on an NFT?

MP: That’s one of my favorite covers of all time. But also the article itself is one of the most rawest articles I think I’ve ever done. I got to do it with a pretty close friend. I’ve spent a lot of time with Tim Layden the last two decades.

For me, that’s a big chapter in my life and an opportunity to let everything out. It was crazy, because that interview, going back to it, I don’t even know the question that Tim asked that made me just feel comfortable and safe and confident in opening up.

SI: That cover was called “The Rehabilitation of Michael Phelps.” Seven years later, do you feel quote-unquote rehabilitated, or is that more of an ongoing process for you?

MP: It’s probably an ongoing process. I don’t know if I will ever understand myself completely, but I will continue to try. I think that process that has allowed me to become who I am today. I’m very thankful for it. I would say we’re on a better journey than I think we were seven years ago—definitely mentally. I know what the word communication is and I know how to do it, whereas seven years ago I’m not really sure I could’ve spelled it. [Laughs.]

SI: How do you feel the conversation around athletes and mental illness has grown in the years since that cover story?

MP: Oh my gosh, it’s night-and-day different. It’s nowhere close to where I want it to be, but that can’t happen overnight. The process we’ve started with dozens and dozens of athletes who have written their own stories and shared their own messages, I think it’s so powerful. Looking at what Naomi Osaka did on her own platform, her Instagram. She put it into words and she explained exactly how she was feeling, what she was going through. I can’t imagine how hard that was. But in my opinion, that helped a lot of people. With what Simone Biles went through at the Olympics, I think it just shows us that our mental health can arise at any given moment. It’s not just going to be something you can tuck away and hope it doesn’t arrive at your most pressured moment.

For me, the more I share my stories, the lower my shoulders drop, the more comfortable I am about my story and about who I am.

SI: Do you have any misgivings about the way the conversation around mental health has evolved? Is there anything that keeps you up at night?

MP: There’s always things that keep me up at night. But that’s how it was when I was swimming, too. I have a story that has stuck with me ever since this guy said it to me on a plane [three or four months ago], and honestly it drives me every single day. This guy said to me that when somebody talks about their mental health, it’s a sign of weakness. This guy was 65, 70 years old. Honestly, I looked at him and I said, “Sir, I’m going to stop this conversation right now, because you triggered me and I’m not really sure what’s going to come out of my mouth next.” I was so upset and so agitated.

I think that’s the one thing I think that fires me up. I’m extremely passionate about mental health and what I’m doing. I feel like if you are that way, then naturally you’re always going to be up at night thinking about certain things and ways to help. But also those are the same things that are getting me up out of bed every morning.

SI: How do we move beyond simply awareness to create meaningful change in the sports landscape with regard to mental health for athletes?

MP: I can talk in terms of the [U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee], because that’s all I know. I saw nothing at all done in the mental health space when I was competing. I had a handful of pretty close friends, brothers and sisters that were swimming in the ’21 Olympics in Tokyo, and they still haven’t seen anything changed in the mental health space.

[The USOPC] says they’re offering [support], but they’re not offering anything. I want people to actually do something. The sport psychologists and all these different groups of people that they have hired, we don’t feel safe and comfortable going to them. So we don’t go to them, and then they still don’t understand why we don’t go to them. So there’s some kind of disconnect, and I’m trying to do some things without being involved with them that will hopefully change for the athletes. There’s too much frustration for me working with my national governing bodies throughout my career. I feel like we have to do it ourselves because nothing else will get done. That’s what I’m going to do, because I want to leave the sport on good terms. My goal from when I started swimming was changing the sport. Yeah, I’ve changed it, but it’s not finished.

We need to make changes, because if not, we’re going to lose more of our Olympic family. I don’t want to lose anymore.

Rob Schumacher/USA TODAY Sports

SI: I was going to ask you about what you think the USOPC response was to your 2020 HBO documentary, The Weight of Gold.

MP: They didn’t like it. [Laughs.] But I’ve spent a long time working with the USOPC, and yeah, of course we haven’t always seen eye to eye, but hopefully at one point we can all just do what’s right for the athletes. That’s really all I care about. I don’t care about doing this to get back at somebody. I’m doing this because I want to see change.

SI: At what point in your career and your life did you realize that anxiety and depression were things to be managed, rather than to avoid? For example, if you think back to something like the bong controversy, how can you contextualize that now with how you were learning to cope with mental illness?

MP: For me, the first time I would say I was in control of it was in ’16 in Rio, where I felt like I was aware of my surroundings, me, everything that was going on. But I also felt like I could see other people struggling who weren’t quite aware of what that struggle actually was. I had Shaun White sitting next to me at a gig. He basically turned to me and was like, “Oh my god, that’s depression? Woah. That’s what I’ve been feeling?”

I think at that point [with the bong], I was just like, How do I figure my life out? I don’t really know what was going on at that point. But I think after my second DUI, in ’14, of not wanting to be alive for those 24, 48 hours, that was the kind of thing where I was like, All right, am I just going to give up? Or am I going to find a different road, a different answer? I need to figure something out.

I think that was the first time where I actually asked for help, and then I was able to manage it, because I was able to get into a routine of something that was healthy for me. I remember the first time I went to a therapist, I was like Oh my gosh, this is going to suck. I don’t want to go in here. This is going to be so brutal. I walked in and I walked out. I felt like a completely different person.

SI: Being famous at such an early age, do you think society is set up to appreciate mental health concerns you or other elite athletes have had?

MP: I don’t know. It’s hard. It’s wild to think about. Going back to it, I was so narrow-focused on what I was trying to do in the pool that nothing really affected me for a long time. And all of a sudden I was basically like, Oh shit. Basically I ran into a wall, like, uh-oh.

Especially now with [name, image and likeness] and all these changes that are happening in sports, especially with social media—yeah, I grew up a little bit in the social media era, the boom of it. But not to what it is today. So yeah, it’s wild. I think coaches, parents, teachers, individuals themselves, we all need to look at that stuff as a whole just because of what can control our brain. How much time do people spend flipping through Instagram or social media? And how many mental health issues have come from that?

SI: With raising a family and also working with kids through your foundation, would you encourage that generation to pursue careers in elite sports, knowing the potential mental health ramifications?

MP: I think if they want to, yeah, 100%. I think for me one of the reasons I was able to have the career that I did and the longevity that I did. My mom never pushed me to do anything. If these kids tell me they want to do something, then I’m going to help them, whatever that is. If they want to tell me they want to be a rocket scientist, then great. Cool. If that makes you happy, then that’s what I want. I want them to be happy at the end of the day and I don’t want my kids to chase my dreams. I want them to chase their dreams.

SI: Where do you want the future of mental health care in sports—and the conversation surrounding it—to look like, in your ideal world?

MP: Obviously, everyone having access to some kind of care. I’d like people to open up more. It’s one thing I always try to encourage people to do, is opening up. I just want people to be O.K. And I want people to also understand it’s O.K. to not be O.K.

Back to that airplane conversation, that guy. That guy is the reason I’m out there doing what I’m doing every single day. I’m trying to change that guy’s mind about mental health. Because if I can’t change that guy’s mind, then I have no shot.

I need to come up with a way to basically—I don’t know if convince is the right word—be able to spread the word about mental health. We’re all gung-ho about physical health. Let’s be gung-ho about mental health too, because they both matter. They both matter for us being our authentic selves.