Here at MusicRadar, we’ve recently been unpicking the often-arcane world of music theory, and just how to read music and understand how chords work on a scientific level. While we vouch for this being an essential and important field to grasp as a music-maker, when it comes down to the real crux of why you want to make music, all of that information isn’t going to make you a complete killer track or song.

Yes, because really, when it comes to building a song or a track, it’s important to grasp how your track actually cuts through and appeals to listeners.

To do that we really need to unpick what it is that makes a song or track work in the first place.

In this feature we’ll analyse a few key song-forms, and think about how we can apply their methodology to our own songwriting to improve how we write going forward.

Types of songs

Firstly, we’ll be referring to both songs and tracks as just ‘songs’ from here on out, while there are some differences, most of the structures discussed apply to both lyric-oriented, vocal-led pop songs and instrumental tracks.

Secondly, let's explain what we mean by the term ‘song-form’. This term relates to the various sections that make up a song - elements like a verse, a chorus and a bridge are core here. Most pop music that you can probably think of is built around a conventional verse-chorus-verse form, which oscillates between the two states (and is usually bridged by a… well, a bridge).

The verses tend to present a rigid melody performed at a more restrained intensity level, as the chorus is all about selling the song’s central hook.

Quite often, this main hook incorporates the title of the song. It’s this counterbalance of intensity that is pivotal to a popular song’s dynamic effectiveness - a constant chorus can be waring quite fast, while a verse which never offers any release is going to have limited appeal and make people feel a bit…well, anxious.

We call this verse-chorus-verse form ‘ABAB’ form and it is the most commonly used in western popular music. But it’s not the only form that's popular - verse-only forms (aka ’strophic forms’ often build verse structures that have a thematic and musical resolution built into their repeating structure.

Usually, these songs are more narrative-driven and it was central to classic folk tradition.

Bob Dylan’s employed the form often, with All Along The Watchtower being a good example. While the song’s simple three chord-roll of Am to G and to F creates a mesmerising centrepiece to the arrangement, Dylan deploys increasingly more vivid lyrics (while the Jimi Hendrix cover version’s mirrored structure allows for plenty of space for a stream of solos).

This cycling structure is also known as ‘AAAA’ form. A slight evolution of that is the AABA form, wherein the verse serves more of a chorus-function. The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night is a good example, where the B part serves as kind of a bridge, or lull in the energy of the track (the part that begins; "When I'm home…"), which is propelled through the spritely verse.

These variations aside, in popular music, the overwhelming majority of contemporary pop songs (at this point in history, at least) follow the ABAB form - many adding a pre-chorus, bridge or post-chorus part too, in order to facilitate a smooth transition.

Writing in the ABAB form

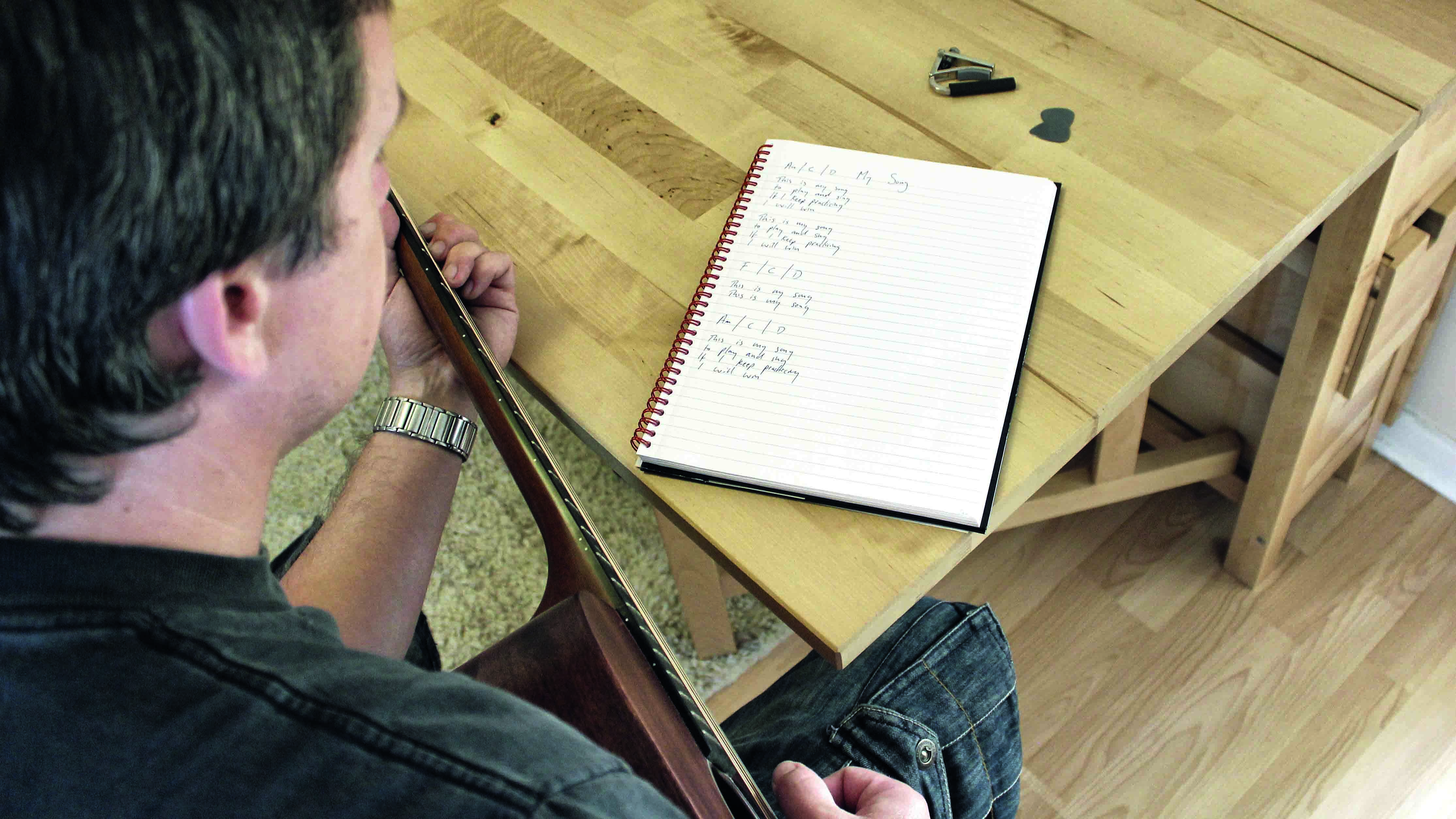

As with all songwriting, the first thing you need to think about when putting pen to paper (or fingers to keys/strings) is not technical - you might have a nice chord loop, or a beautiful melody kicking around (which you can certainly deploy in your song) but that’s not at the core of what makes a song work.

You need to be clear in your mind about what you want to express.

Love songs are popular, as relationships are a universal language that (most) people can get onboard with, as are songs/tracks about letting your hair down and having a good time.

Both of these are up there as the most common song themes, and they lend themselves well to the tension-release-tension structure of the ABAB form - with the verse part establishing the situation.

In a romantic song, this verse narrative could tell a tale of unrequited love. In the case of a ‘going out and partying’ song - for example Black Eyed Peas’ I Gotta Feeling, cementing the excitement ahead of the ‘going out’ with the chorus itself being the equivalent of the release and euphoria of a good night in a club.

The romantic song could be the culmination of the story, a dedication of love or, contrarily an outpouring of anger that the target of the song doesn’t love the protagonist back.

Examples of classic verse-chorus-verse ‘love’ songs include:

Just the Way You Are - Bruno Mars

You’re Beautiful - James Blunt

I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing - Aerosmith

If I Ain’t Got You - Alicia Keys

Someone Like You - Adele (as an example of ‘unrequited love’)

Examples of classic verse-chorus-verse ‘partying’ songs include:

Party in the USA - Miley Cyrus

Get Lucky - Daft Punk

I Love Rock’n Roll - Joan Jett

Tik Tok - Kesha

The popular success of each of the above songs is entirely down to how they balance these two simple, universal themes within their basic balanced song forms.

As the old adage goes - if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Verse-chorus-verse is a sure-fire way of communicating simple, uncomplicated themes and feelings to a mass audience.

Of course, there are many more themes that popular songs express, and many more song forms that can help tell more nuanced (and arguably, more interesting) stories.

Bridges - which many verse-chorus-verse songs also have - tend to be used to add further dynamic interest and might be a place where the lyrical narrative takes an unexpected turn, or off-roads the listener into a new musical landscape before pivoting back to the safe, familiar ground of the verse or the chorus.

Verses and choruses might be separate ‘A’ and ‘B’ sections (with the bridge, in this context, being a ‘C’) but each element only exists in opposition or support of the other sections.

Verses lead up to the chorus, choruses react (often explosively) to the coiled tension of the verse, while second verses might add extra musical elements now that the structure has been firmly established.

The take-away here is that, though we’re thinking of these elements as standalone parts, in reality they’re anything but. A good chorus just won’t work without a surrounding verse structure.

It’s often the case that verses don’t lead directly into a chorus, often a ‘pre-chorus’ is required to make the transition (musically, dynamically and narratively) into the huge chorus.

A good example of this in action, is in the track Blinding Lights by The Weeknd. While the verse keeps the action constrained and somewhat moody (albeit, with a springy rhythm section keeping momentum), the pre-chorus transforms the melodically looser verse into a more defined, tension-stoking framework.

‘Sin City’s cold and empty (Oh!)’

‘No-one’s around to judge me (Oh!)’

‘I can’t see clearly when you’re gone’

‘I said…’

This then is the perfect springboard for the infectious chorus. It's is a prime example of laying the groundwork and guiding the listener into a chorus with ease. People like the feeling of anticipating what's going to come next - almost like ascending a rollercoaster before the breath-taking plunge.

Though we’ve talked through the general principle of song-forms here, in reality there are many ways you can juggle these verse, pre-chorus, chorus and bridge sections. The core thing to remember is that you’re using these components to take your listener on a journey. You're the storyteller here.

Even if your song is lyric-free, the music is still communicating something, so think about how to maximise that communication.

Read the previous instalments in our ongoing theory series below

- The pillars of music theory made simple

- How to become a master of melodies

- A quick guide to reading music

- How to understand rhythm when reading music

- Understanding scale theory

- How to use triads

- How to use suspended chords

- Tried and test chord progressions