When it comes to properly appreciating a figure as mythic as Pele, the reality of their career can get lost amid the reverence over time, so it is worth recalling something actually said about him on one of the days he played. This was to be one of his greatest days.

In the hours before the 1970 World Cup final, Tarcisio Burgnich – about as grizzled an Italian defender as they come – kept repeating one phrase to himself.

“He’s flesh and blood, just like me.”

He’s flesh and blood, just like me.

“I was wrong,” Burgnich later said. Pele had that day made himself immortal. His pass for Carlos Alberto has become one of the most famous images from one of the most famous football moments. It wasn’t just a crescendo to an orchestral move that served as a crowning moment, but also the perfect illustration of what elevated him above everyone else. This wasn’t something sensational, such as a bicycle kick or ridiculous run, but instead a simple sideways ball. Well, it was that, but also a piece of extraordinary perception, precision and timing that showcased in a millisecond how Pele could see the game to a greater depth than anyone else. From the very corner of his eye, he played a pass that was perfect for the right-back to run onto at full pace to power the ball into the bottom corner.

It is because of that, many images of Pele himself endure as he sadly passes at the age of 82. They are the regal figure of 1970 as well as so many moments like the shot from the halfway line against Czechoslovakia, the dummy against Uruguay, the nutmeg of Eusebio and just lifting the game’s most famous trophy then doing it again and again.

There is also the image of Pele the film star, the game’s great ambassador and – more controversially – the corporate shill and even dictator’s tool. Such complications are reflected in how the origins of his famous nickname remain unknown, ensuring Edson Arantes do Nascimento will forever be known as Pele, and it initially aggravated him. His fame as a precocious talent soon lapped any residual irritation several times over.

On that, to realise how he became all of these things, it is worth laying out another image. That is of a spindly 17-year-old – when, physically, he was very little “flesh and blood” at all – walking into a situation where there was considerable doubt.

As Brazil prepared for their final group game in the 1958 World Cup, against USSR, they didn’t just need a result to go through. They needed to banish all manner of ghosts.

Incredible as it is to think now, the World Cup’s most successful ever winners were at that point the competition’s greatest losers. They had never lifted the trophy, but had remained levelled by the worst possible defeat. The 1950 home loss to Uruguay dominated Brazil’s national psychosis, creating a neurosis far removed from the joyous football they would become famous for.

“I’d suffered as a nine-year-old, crying so much,” Pele himself said, “and promising that one day I’d avenge that Maracana defeat.”

He would do so much more than that – but not initially. Pele went into that World Cup with doubts about his fitness and his mindset. He had been injured getting to Sweden and a psychologist even recommended to coach Vicente Feola that he didn’t have the necessary fighting spirit.

Feola instead knew he had so much more than that. He felt it would be insanity to do anything other than put Pele and Garrincha in for the match against USSR.

“I felt a surge of emotion course through my veins,” Pele said of the moment the anthems started. “This was what it was all about.”

This was the moment that football became all about Pele, for so long the standard against which everything was set.

Brazil were transformed, this mere 17-year-old was game-changing and match-winning, in a manner that has not been seen before or since.

It is just as remarkable now given all of the focus on the scoring records of Leo Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo in World Cup knock-out matches.

In Pele’s first World Cup, at the age of 17, he scored the winner against Wales in the quarter-final, a hat-trick against France in the semi-final and two against hosts Sweden in the final. Talk about clutch. No one has dominated and defined a World Cup like that, which makes it all the more symbolic that Pele has won the World Cup more than anyone else. This is why it will always be associated with him more than anyone else. Pele is the ultimate World Cup player.

He also gave the world something new in another sense.

Pele has described his first strike in that 1958 final as the favourite of his career because “no-one had seen a goal like that before”.

In one flowing moment, and despite later admitting that he was initially just going to hit it, this teenager had the presence of mind and imagination to suddenly lift the ball over Reino Börjesson’s head before running around the centre-half and driving a volley into the bottom corner.

Many will have seen similar goals since, often executed in a more sensational manner. One was Paul Gascoigne’s against Scotland in Euro 96. The spectacle isn’t the only point, though.

As with that attempt from the halfway line and that dummy, it was that Pele had done something nobody had even imagined before, and this on the greatest of stages.

He was, like most of the true greats, a pioneer. He did things nobody had thought of, expanding the parameters of the sport for everyone who followed.

It is just another way Pele could be described as football’s Elvis Presley. He was a pioneer and the sport’s first international superstar. Timing, as with so much of his greatest moments, was integral to this.

He dominated a World Cup just as it became a televised event and then had his career performances, in 1970, just as colour television took off. It added an aura to his greatness, such vivid football forever captured in vivid technicolor.

It can’t go without saying that this was another essential element of his legacy.

“He was the most inspiring image that we’d ever had of a poor black boy,” politician Benedita Da Silva said in the recent Netflix documentary. This is crucial.

Pele was not just football’s first true international star but a globally revered black person – and that at a time when the USA hadn’t even passed the Civil Rights Act. Only a decade later, he would be serving as soccer’s ambassador to the country.

He has reflected on this in his autobiography.

“It is almost like a race apart – not black or white, but famous. Being in Africa was a simultaneously humbling and gratifying experience for me. I could sense the hope the Africans derived from seeing a black man who had been so successful in the world. I could also sense their pride in my own pride that this was the land of my forefathers. It was a realisation for me that I had become famous on several different levels – I was known as a footballer even by people who didn’t really follow football. And here in Africa, as well as that, I was a world-famous black man, and that meant something different still.”

All of this, and particularly so young, also brought other challenges and realities that further affect Pele’s legacy as well as creating the kind of classic arc that really makes the great sporting careers.

The Brazilian state soon declared him “a national treasure”, meaning he was legally prohibited from leaving the country to accept countless offers from Europe. This meant the only glimpses half the football world saw of him were at World Cups or when Santos won the Copa Libertadores to play in the Intercontinental Cup. There, he still destroyed the best Europe had to offer, most memorably nutmegging Eusebio in a 5-2 evisceration of Benfica in a game seen as confirming the true king.

This also marked him out for treatment in a physically brutal football era. While opponents like Just Fontaine would comment on how they wanted to applaud him when he did something audacious on the same pitch as them, it didn’t prevent their teammates trying to stop him any way they could. Pele was effectively kicked out of the 1962 and 1966 World Cups, meaning the stadiums of England never became the stages they should have been for a player in his prime.

Pele was so incensed that he vowed not to play in 1970. This was unacceptable for Brazil’s military dictatorship, who had made winning the great trophy a “government issue”. The documentary makes clear that he did not want to play in that World Cup. It is indicated that the country’s military dictatorship didn’t just instruct him to play. They demanded victory.

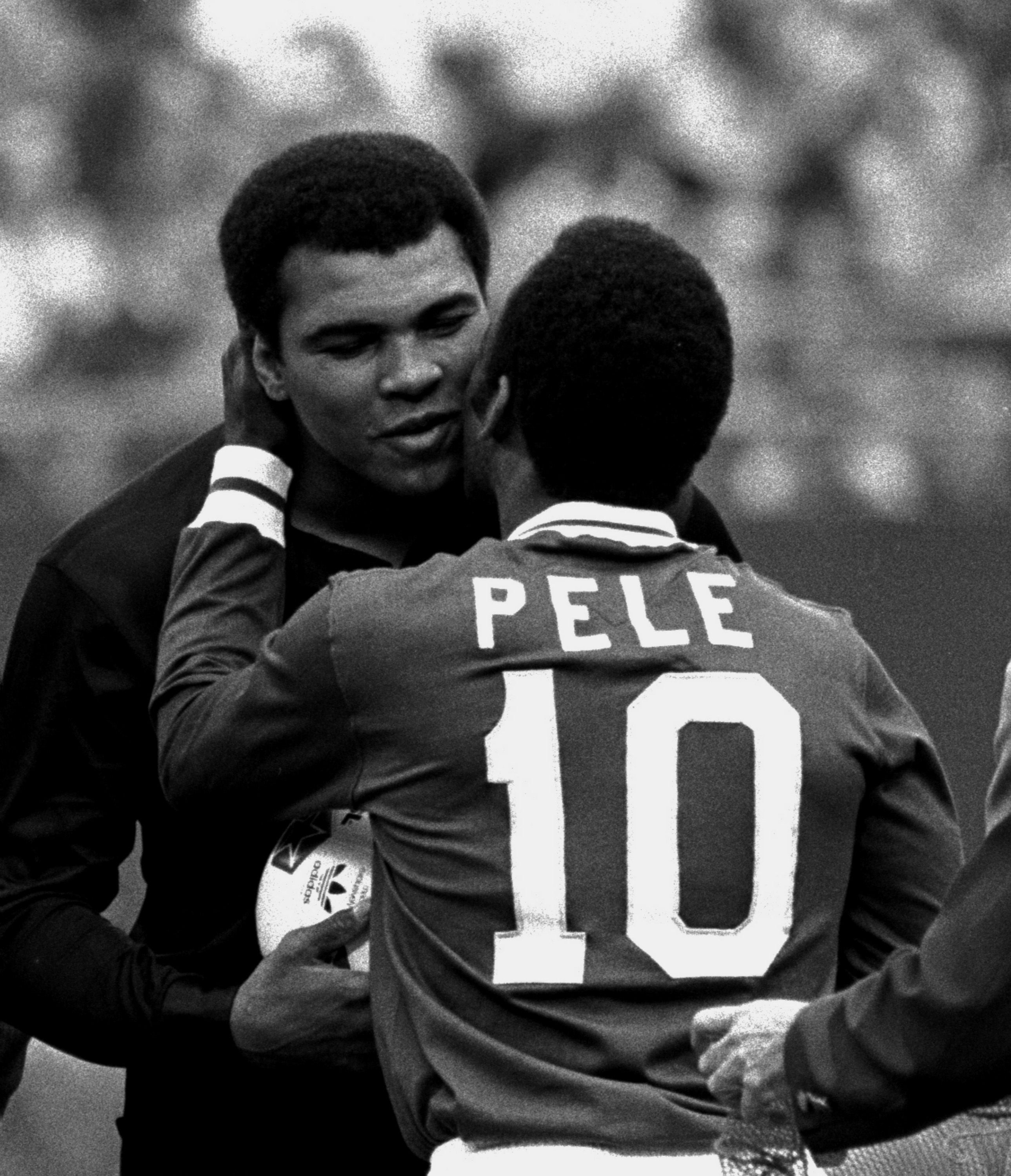

It set the narrative strands for a great sporting storyline in a Muhammad Ali-style comeback, but also something more sinister, that contrasts with Ali.

Pele became seen in some quarters as someone who aided a brutal dictatorship. Teammate Paulo Cesar Lima was one of the most excoriating.

“I love Pele, but that won’t stop me criticising him. I thought his behaviour was that of a black person who only said ‘yes, sir’, a black person who is submissive, accepts everything, doesn’t answer back.

“It’s one of the criticisms I hold against him to this day, because one single statement could have gone a long way in Brazil.”

This unwillingness to question power fed into a more complicated second act, where the football world’s first black star was questionably recast as this corporate stooge more than a political stooge.

His popularity unquestionably receded. For a lot of this millennium, he just wasn’t as popular.

It is another way that there are parallels with Elvis, but from this perspective only because the musician also feels someone primarily revered by previous generations. The passage of time and proactivity of Diego Maradona ensured that the Argentine for a long time became the game’s great standard-bearer, the synonym for football greatness itself. It was for all these reasons that Maradona had a “cool” that Pele could never have.

It cannot be overlooked, however, that Pele had a fame no-one had ever seen. This went hand in hand with complications to these images that were also unseen. When the Jules Rimet trophy that he had lifted three times was stolen in Brazil, never to be found again, Pele refused to blame the thieves. He blamed the society that created their desperation. Journalist and friend Juca Kfouri meanwhile argued that, unlike Pele with the military dictatorship, Ali had no risk of being tortured.

His fame became a weapon. It also became something else.

It ensured he became one of those rare figures that people just wanted to be near, a living legend in the truest sense of the word.

This is why he was chosen as football’s great evangelist in the USA with the New York Cosmos. This is why even Andy Warhol was commenting on his celebrity.

“Pele is one of the few who contradicted my theory: instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries.”

Or, really, immortality.

This is at the heart of it all, what really made Pele. You just have to watch him play football. And when you do, even amid the slower pace of the 1950s and 1960s, something else strikes. Pele doesn’t just look better than everyone else. He looks like he’s from another space-time. He looks like a player from 2023 unfairly dropped in on a more basic era. This is how he could imagine feats others couldn’t. This is how he could do things others couldn’t. It is frightening to think what he might have been capable of with modern coaching and sports science.

It doesn’t really matter, though, nor does the debate about the greatest ever. Pele’s sad passing does come at quite a time, given he still lived long enough to experience such a historic if controversial World Cup. It’s still his trophy more than anyone else’s. That’s still as grand a claim as anyone could have to greatness.

There’s then the human reality at the heart of it all.

For that World Cup final in 1970, Pele was under such extraordinary political pressure by the dictatorship that his reaction on reaching the Azteca dressing room didn’t really fit with such a moment of pure fulfilment.

“I didn’t die!” he shouted, before twice repeating the refrain. “I didn’t die! I didn’t die!”

He instead made himself immortal.