Before each federal election, the heads of the Commonwealth departments of treasury and finance release a report on the state of the government’s budget, together with updated economic forecasts.

It is known as the pre-election fiscal and economic update, or PEFO.

The 2022 PEFO came out on Wednesday afternoon.

The Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998 requires publication of a PEFO “within 10 days of the issue of the writ for a general election”.

This year’s was easy for Treasury and Finance to compile. PEFO came a bare three weeks after the budget on March 29, and not a lot had changed.

The economic forecasts are identical. Treasury would have heaved a large sigh of relief when last week’s unemployment numbers came out unchanged at about 4%.

Unemployment forecast like budget’s

If they had come out significantly lower, Treasury would have had to update not only the economic forecasts but also revenue and spending forward estimates.

The unemployment rate affects both income tax and welfare spending. In PEFO the forecast is the same as at budget time, so no recalculations are required.

Yes, the economic outlook is volatile – but it is the same volatility as at budget time. It does not provide a reason for changing the forecasts.

There are a few small adjustments to spending. They net out at almost nothing. The estimated deficit in 2022-23 is $77.9 billion, close to the budget’s $78.0 billion.

Secret spending that never was

New spending since the budget includes some infrastructure projects and community development grants (unsurprisingly, prior to an election) but no significant new programs.

A mystery in this PEFO is the removal of provisions for some secret decisions taken but not yet announced. Reversing those decisions amounts to a saving, which has been used to offset some new spending.

Decisions taken but not yet announced have become so common that this year PEFO refers to them by their own unlovely acronym: DTBNYAs.

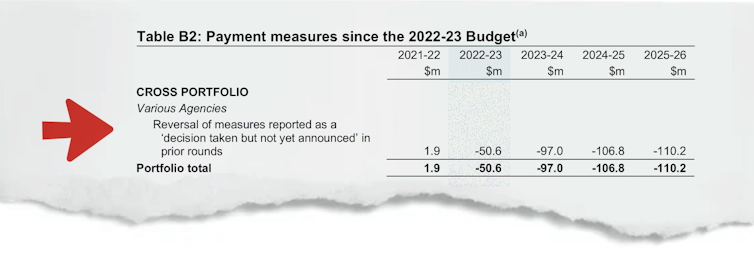

They are recorded in Appendix B as “Across Portfolio. Various Agencies. Reversal of measures reported as a decision taken but not yet announced in prior rounds”.

They amount to $50.6 million in 2022-23, climbing to $110.2 million in 2025-26.

What were these decisions? We don’t know. They weren’t announced. We do know the government has had second thoughts and reversed them.

Second thoughts

It might have been because the needs the measures were designed to meet have changed, which would be a sensible and rational reason for their reversal.

Or it might have been because they were foolish and misguided decisions, meaning someone put a pencil through them to save the government embarrassment. We can’t tell.

Either way, it is not a great look for budget transparency.

Read more: Labor's budget reply goes big on aged care, similar on much else

This is not the same as the separate provision in the contingency reserve for items that cannot be disclosed for commercial or national security reasons.

Often, these relate to procurement negotiations still underway – including, as noted in PEFO, the Australian Electoral Commission’s information technology modernisation program.

There is a good argument that the amount of money the government is willing to pay to a private provider should not become public until negotiations are over.

That’s normal, and the 2022 PEFO continues the practice.

PEFO is an opportunity to speak the truth

PEFO is written by the secretaries of the departments of finance and treasury rather than their political masters, meaning they are about the only time the secretaries can speak freely.

Sometimes, the small details they include give an insight into what they are thinking. In 2016, for example, the media identified an inclination on the part of the departmental heads to push harder than the government in cutting spending.

It is a concern that seems quaint now. A return to surplus is a distant prospect.

So if PEFO is essentially the same as the budget, do we need it? The answer is yes.

It makes budgets and elections more honest

For a start, it makes the budget or budget update that precedes it more honest.

If ministers know that the top budgetary officials will soon release an independent report, they will be less inclined to interfere with budget forecasts or invent over-optimistic numbers, knowing they will be found out in PEFO.

Even more important, it means election promises are more likely to be kept.

Before PEFO was introduced in 1998, when a government changed hands it was routine for the newly-elected government to renege on its promises by saying something along the lines of:

…we are shocked, just shocked! We had no idea how bad the country’s finances were!

PEFO has done away with that excuse forever. It means both sides of politics know the state of the books going into the election.

Parties’ promises are made with that full knowledge. Incoming governments no longer have a budgetary policy excuse for dropping their promises.

For that reason alone, PEFO is worth keeping.

Stephen Bartos does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.