It's a strange world indeed when even Paul McCartney can't get the respect he deserves.

Sure, he's half of the greatest songwriting team that ever existed. And yes, his little band The Beatles did forever change the face of popular music, becoming the biggest-selling and best-loved act, well, ever. Oh, and he's won just about every award a human can without single-handedly winning a war or something. In short, he's done it all.

You just think of him as Beatle Paul, yet in my opinion, he is the best of all bass players. He’s number one

Rick Rubin

But hey, what about his nifty bass playing? Who talks about that? In truth, many people do - and have in the 50 years since The Beatles became an unparalleled cultural force.

Uber-producer Rick Rubin summed this up nicely earlier this year. "You just think of him as Beatle Paul," said Rubin, "yet in my opinion, he is the best of all bass players. He’s number one.”

John Lennon himself had no doubt about the importance and impact of Paul's bass work, going on record in his last documented interview to say, "Paul was one of the most innovative bass players ever. Half of the stuff going on now is directly ripped off from his Beatles period.”

McCartney didn't set out to become a bassist, somewhat reluctantly taking up the low-end in 1961, when The Beatles' first "real" bass player, Stu Sutcliffe, John Lennon's art school friend, decided to quit the band to stay in Hamburg, Germany where the group had been playing a now-legendary slew of residency gigs.

From the word go, once I got over the fact that I was lumbered with the bass. I did get quite proud to be a bass player

Paul McCartney

Almost immediately, McCartney proved to be a natural on the instrument, transforming himself and The Beatles into innovators and trend-setters. He once told Bass Magazine, "From the word go, once I got over the fact that I was lumbered with the bass. I did get quite proud to be a bass player, quite proud of the idea. Once you realised the control you had over the band, you were in control. They can’t go anywhere, man. Ha! Power!"

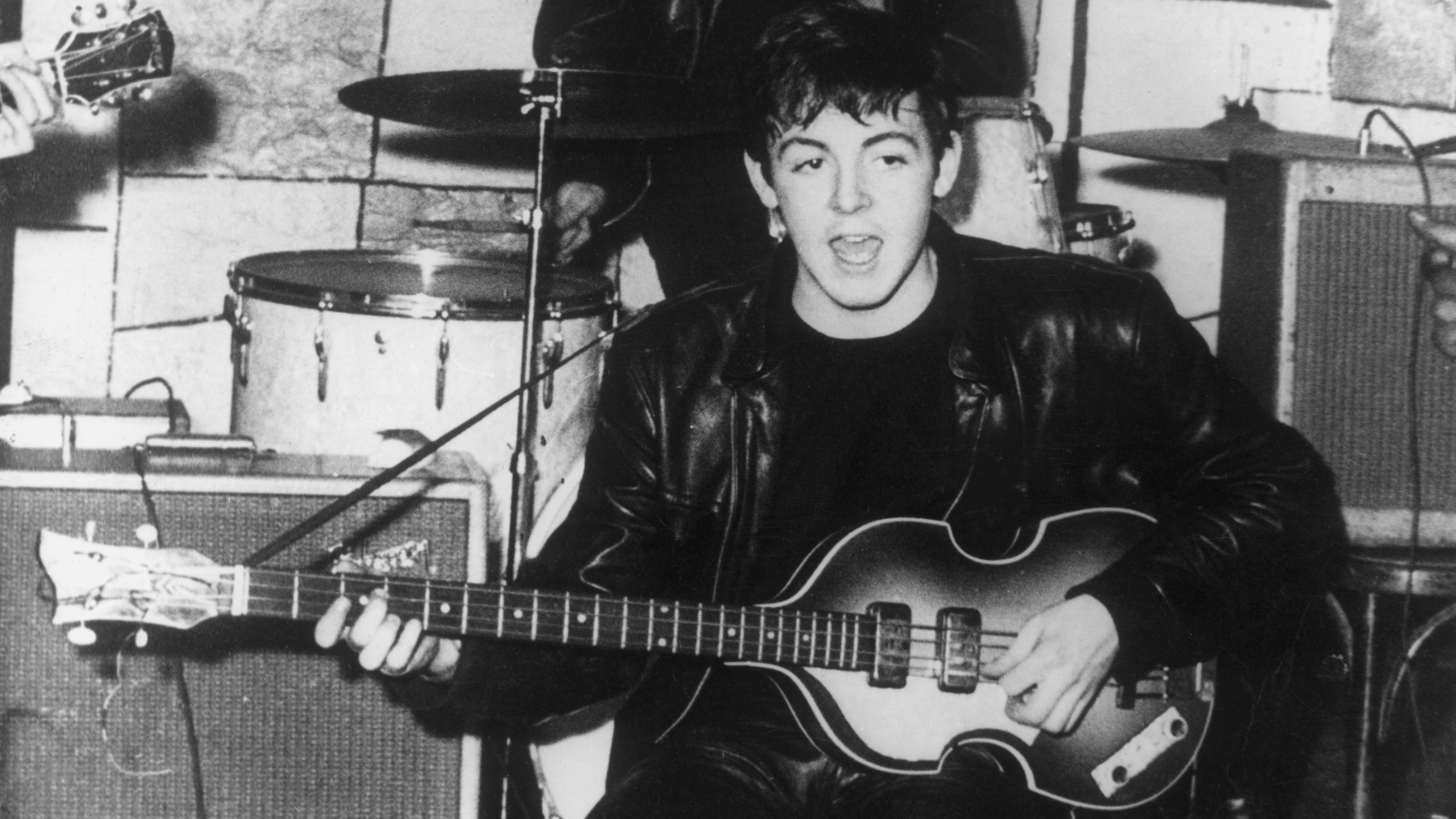

The image of McCartney with the violin-shaped Hofner 500/1 bass is one that will forever be burned into the minds of music lovers everywhere - in fact, the Hofner is commonly referred to as the "Beatle bass."

Chops-wise, Macca's in a class of his own - he can play guitar, piano, drums, fiddle, sax, spoons, washboard, electric fence, tire iron, light bulb, red pepper and probably anything else you put in his hands.

But it's the Beatles bass exploits of Sir James Paul McCartney CH MBE we're celebrating today, and here we'll tell you why he's really Fab...

All My Loving (1963)

Already realizing that driving, standard rock 'n' roll eighth notes wouldn't cut it in such a sprightly number, McCartney played a quarter-note walking bassline that provided real lift.

His choice of notes, along with bouncy dynamics, approximated both R&B and jazz - a perfect counterpoint to the ringing guitar patterns and Ringo Starr's swishy hi-hat.

Perhaps more amazing than McCartney's intuitive playing (shifting approaches during the chorus and again in the guitar solo) is that he could do it all - and still does - while singing lead...and not looking at the fretboard. Try that on for size!

Tell Me Why (1964)

Ringo Starr's dazzling dance hall drumming drives this effervescent winner from A Hard Day's Night, but McCartney's bass playing, a variation of the walking pattern in All My Loving, is a sophisticated smash.

The verses see McCartney sticking more to root notes, laying back slightly behind the rhythm guitars, but he takes off again merrily during the choruses, working off of Starr's wicked cymbal crashes with real pizazz.

Eight Days A Week (1964)

On one of The Beatles' poppiest, lighter-than-air hits, McCartney began to assert the bass in a more profound manner.

Amid electric and acoustic guitars, and those all-important handclaps, the bass is big and full of "oompf" - McCartney, who grew up loving skiffle and the early recordings of Elvis Presley, gets an almost upright sound from his Hofner.

His use of space here is highly evolved - the influence of Motown is showing in how he rolls his notes during the verses.

Nowhere Man (1965)

At this time, McCartney began using a left-handed Rickenbacker 4001S (although he still employed his Hofner), which, because of its longer scale, provided more sustain and a wider range of tones.

One gets the impression that it's the Rick on Nowhere Man - going up against the chiming, trebly guitars and Ringo's lively snare rolls, the bass sounds especially midrangey, with less "woof" than the Hofner.

Musically, Macca's performance is independent from the rest of the song - it glides and bops along, doing whatever feels right. But responding to Lennon's poignant lyrics, he achieves something of a dual narrative, one that is appropriately wistful and melancholy.

Michelle (1965)

McCartney's early bass recordings were notable for their energy and exuberance, but on the heavily acoustic Rubber Soul, particularly on his love ballad Michelle (which was written to emulate Chet Atkins' style of fingerpicking), Macca created a wondrously nuanced, stylized mood piece.

Remarkably, the smooth and silky bassline which serves as a poetic counterpoint to the guitar chords, riding lightly off of Starr's hi-hat and stickstick, was thought up in the studio on the spot.

"I never would have played Michelle on bass until I had to record the bass line," McCartney revealed to Bass Player magazine in 1995. "Bass isn't an instrument you sit around and sing to."

Paperback Writer (1966)

Oddly enough, it was John Lennon who wanted a boosted bass sound on Paperback Writer - he'd heard a Wilson Pickett song and was knocked out by its low-end punch.

In response, newly installed engineer Geoff Emerick devised a way of making the bass super-loud by using a loudspeaker as a microphone - one of his first innovations.

McCartney's playing, of course, reigns supreme. With George Harrison's gritty guitar hook leading the way, he tears out of the gate with an absolutely blazing series of roller-coaster runs, catching his breath occasionally and then going back for more unexpected dives and spins.

Rain (1966)

If the nasally sneer of John Lennon's voice and the metallic, rat-a-tat-tat sound of Ringo Starr's drums weren't enough to throw people ("Is that really The Beatles?!), then Paul McCartney's ginormous bass on Rain was a total head-turner.

McCartney occasionally capoed his Rickenbacker during this period, and some have speculated that he did so here. Much of his loping, octave-centered patterns sound as if they were played high on the neck. As he had done on other Beatles songs, he played a counter melody to the guitar riff - his own subtext, only this time bursting through the whole.

The interplay between McCartney and Starr at the 2:28 mark before the ride-out is as astonishing now as it was in 1966.

Taxman (1966)

MusicRadar readers voted Taxman as the number 13 greatest bassline of all time, and with good reason: it's the main musical hook in a song that's overflowing with them.

George Harrison's biting piece of social commentary was his first major-league composition (it was awarded the first spot on The Beatles' landmark Revolver album), but it would be unthinkable without McCartney's elastic, memorable bass riffery.

And that's McCartney doing the crazed, early psychedelic guitar solo (repeated at the end). Not too shabby, eh?

Getting Better (1967)

One could easily make a case for almost the whole of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band as being a "greatest" bass performance.

The Beatles, led here by McCartney, ushered in a new realm of songwriting and production aesthetics, forever changing the concept of the record album experience - all of which was reflected in the group reaching new levels of musicianship.

McCartney's own Getting Better neatly encapsulates the breakthroughs he made as a bassist in 1967. With an entire track of his own on which he could experiment with overdubs (EMI Studios had graduated to four-track), Paul serves up a lively, propulsive rhythm, bolstering the effect of the cracking snare and popping off with effective slides.

Humorous, carefree, bright and sunny - like the Summer Of Love Sgt. Pepper helped create.

Everybody's Got Something To Hide Except Me And My Monkey (1968)

The 1968 double album The Beatles (also known as The White Album) was a divisive affair - the band bickered constantly about anything and everything from girlfriends to cookies.

Geoff Emerick walked away from the sessions (he returned for Abbey Road), and even Ringo quit for a few days.Even so, the music on the two discs ranks among the The Beatles' finest.

Everybody's Got Something To Hide saw Lennon blissfully having his way with meter and structure, but McCartney hung right in there and grooved like a mofo, playing with roots and fifths and riding every twist and turn of his partner's erratic waves.

It's a blast when McCartney rams down the eighth notes on the chorus, but his best bit is during the breakdown, after the "C'mon, c'mon, c'mon" section, when he busts out a burping line that leads right into the wham-bam guitar. Great stuff!

While My Guitar Gently Weeps (1968)

With Eric Clapton sitting in on lead guitar, The Beatles sans John Lennon cut what was then George Harrison's premier writing effort. McCartney played piano during the initial recording and laid down his bass as an overdub.

If there were ever any doubt as to McCartney's role as a team player, it can be put to rest by listening to his bravura playing here. For the most part, he keeps his lines simple and tidy, but that isn't to say they aren't loaded with emotion.

Underpinning Harrison's terse chunka-chunk acoustic guitars during the verse and chorus sections, McCartney picks an economical pattern in the bridges that is sweet and vaguely joyous. And then it's back to the heavy.

A masterful piece of musicianship, befitting a classic song.

Come Together (1969)

John Lennon might have nicked Chuck Berry's You Can't Catch Me on this swampy, bluesy bit of rock 'n' roll, but Paul McCartney's bass playing - spooky, sinuous, throbbing and groovy - is as original as it gets.

McCartney was hurt that Lennon wouldn't let him sing along in the studio (although he did track a vocal overdub), but he sucked it up and made his other contributions count, even writing the electric piano part that John would eventually play himself.

Paul's work on the four-string is, as usual, thrilling, helping to create Come Together's magical, mystical and unshakable spell.