Steve Braunias on a beautiful collaboration

What does history feel like when it's being made, when some of the best minds of a generation drag themselves through the Māori inlets at dawn looking for a party, looking to get high, looking to make art out of their weird little country at the edge of the world? New Zealand in the late 1960s shimmers with so much fun and excitement as depicted in the new pictorial biography of one of our greatest living artists, Robin White: Something Is Happening Here.

Much of the book focuses on her later period as a painter and printmaker in Dunedin and the Kiribati Islands. There are a range of essays, and a close overview of her work. It’s serious, proper. But the book most happily and noisily comes alive in the section devoted to her crucial few years on the pretty tidal coastline at Paremata, Wellington.

White graduated from Elam art school and got a job in 1969 teaching at Mana College in Porirua. Her students included Geoffrey Crombie, who joined Split Enz as Noel Crombie, and Greg Flint, that gentle, doomed soul who later set himself up as an art dealer. She also met someone who became a profound influence: Sam Hunt.

The two were lovers, briefly, then friends, deeply. Hunt was at the centre of things. He was connected, wildly social. He knew poets Meg and Alistair Campbell at Pukerua Bay, and Denis Glover at Paekākāriki; Hunt lived in a boatshed on the Pāuatahanui Inlet, and called that stretch of shore Bottle Creek in honour of the constant partying. Friends came and went, including painter Don Binney and writer Jack Lasenby. One guest recalls in the book, "The partying moved between Porirua, Paremata and Paekākāriki, largely coordinated by Sam who at the same time found time to write prolifically."

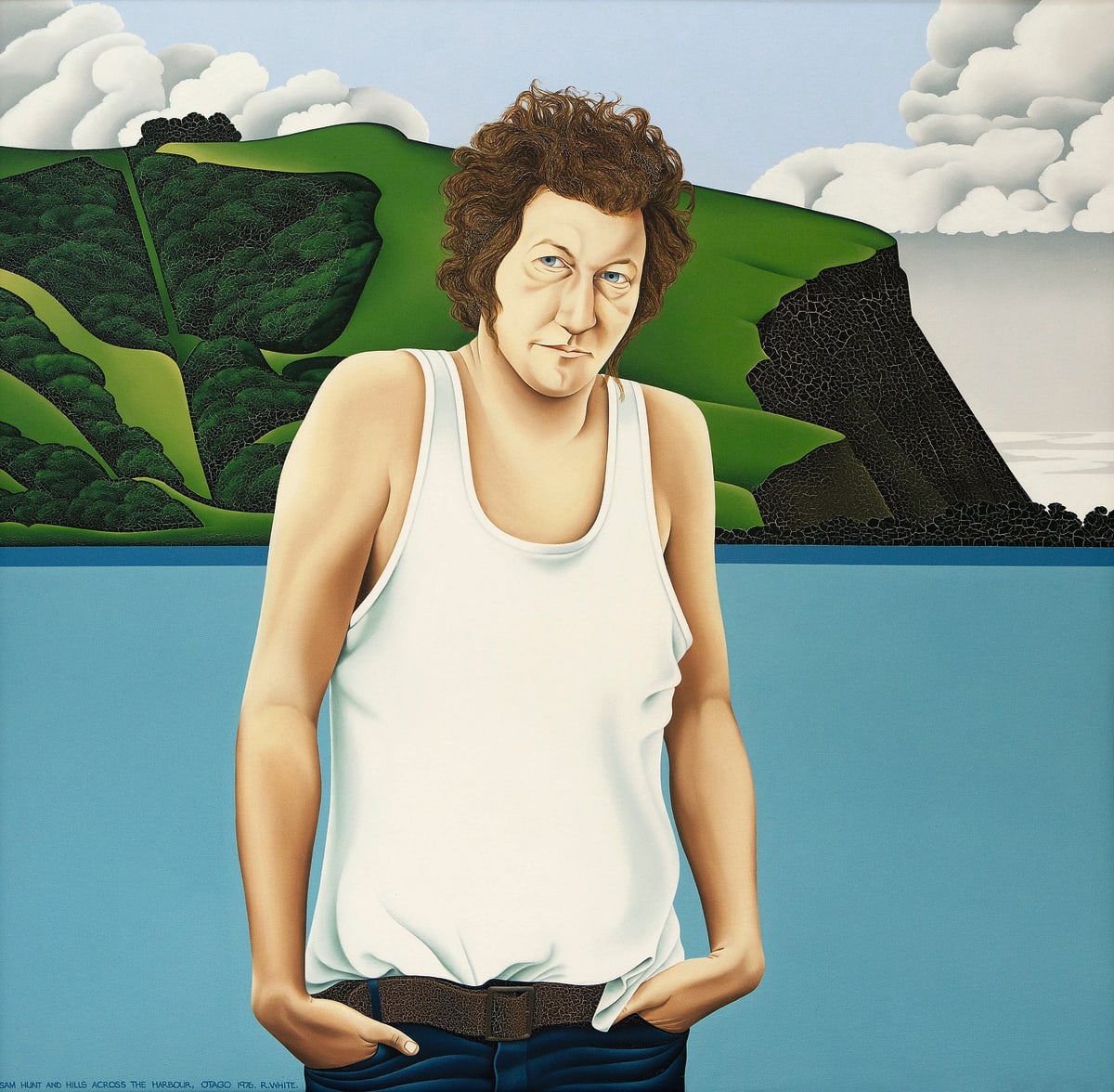

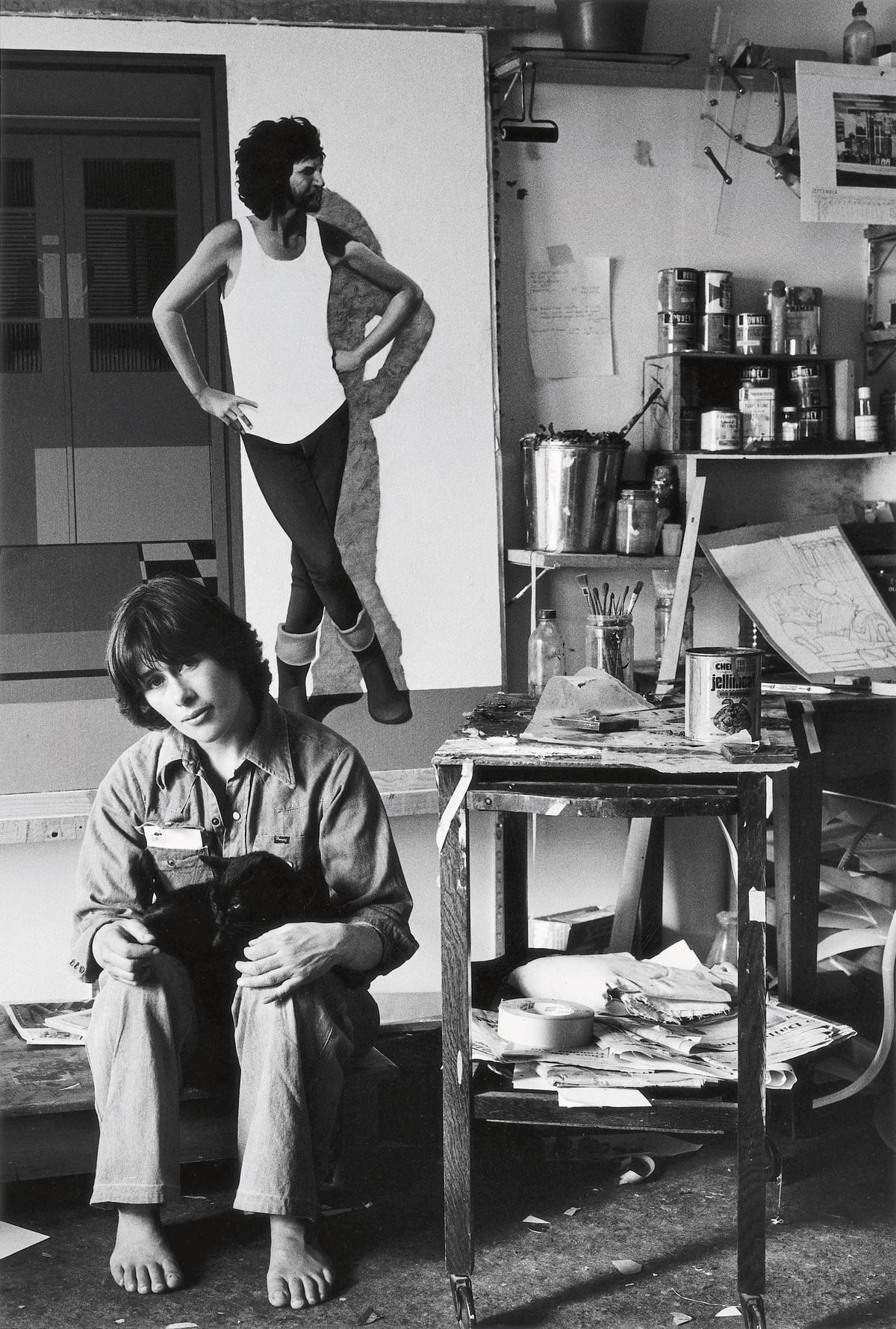

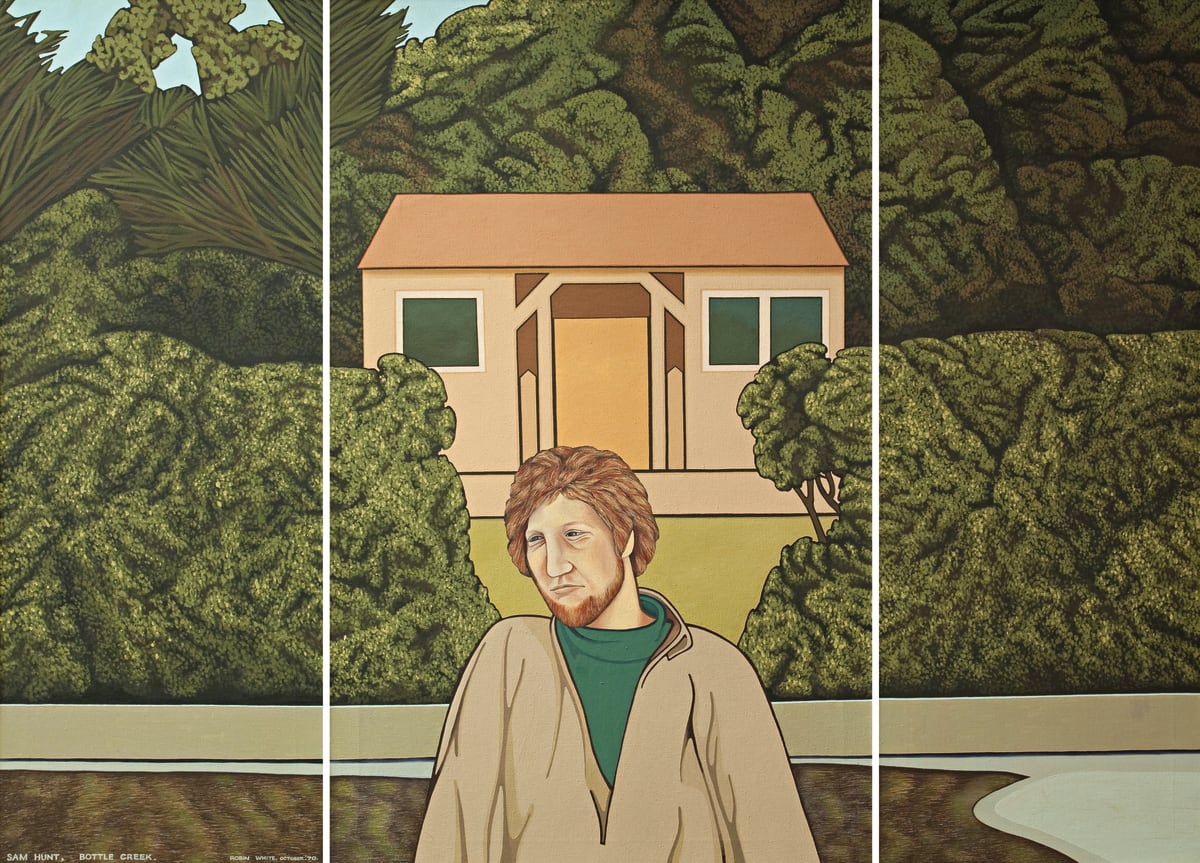

A common, snobbish misunderstanding of Hunt is that his poetry is somehow coarse – the shouting bard, a stranger to the civilising influences of the English departments. In fact he has always operated as a fine and sensitive artist. Like White, he was drawn to the small towns, the quiet afternoons, the long shadows; in his poems and her pictures, the two visionaries formed a kind of collaboration, both capturing New Zealand with the same affection, the same intent. They were on fire during those Paremata years. White painted Hunt, and turned him into an icon. He was the hero of her work, a super-bohemian in a bright white singlet. She painted Mangaweka, Maketū, and Mana, and turned them into icons, too. Hunt meanwhile was writing some of best poems of his life. White: "He worked – well, he worked and he didn’t work, but his mind was always working. I had that encouragement and nourishment. He would come stumping up the path, calling, 'I’ve got a new poem'."

White's book makes you wish you were there, part of the scene. More so, it makes you wish you were able to see her create her now-famous images of such bright clarity – the flat surfaces, the beauty of form – that it would have been like seeing New Zealand for the first time. Her gift was that she showed you a land that you immediately recognised but was assembled in a totally different way. As art critic Patrick Hutchings described her work, "She will coolly show you what you already know but had not allowed yourself to realise."

White herself says, "I saw Bottle Creek, and I saw the house and the hills, and Sam, and put them all together." Tempting to imagine New Zealand culture back then as a wilderness, a vacuum. It’s true that not a lot was going on anywhere for vast periods of time – every day was like Sunday, silent and RSA – but both Hunt and White had their teachers, their traditions, and both practised their own idea of regionalism. In a 1973 interview in Landfall, Hunt ("I think I've got $8 in the Post Office savings bank") spoke in awe of the open road, "the pool tables and the hills and the horses", and said, "That's why I'm a great admirer of Allen Curnow. People are always knocking him down but I stick entirely to his theories on regionalism. Here I am in I973 agreeing with what he said in the 1930s pretty well entirely." But outside of the English departments no one had ever heard of Curnow. Hunt and White were popular artists, low-falutin'. They drew a crowd and along the way created a new kind of New Zealand culture.

It was all very well to discuss regionalism in a classroom but both White and Hunt preferred to experience it. They shared a passion for a New Zealand institution: the road trip. "Setting off in her VW Beetle, they would visit friends in the North Island, stopping by the side of the road so she could photograph scenes that took her eye. In this way she conceived the idea for future paintings of Mangaweka…Much of Robin’s early work takes a slice of small-town New Zealand and transforms it into an archetypal image, a painterly parallel to Hunt’s practice as a poet."

On the road, stopping to take the temperature of whatever no-horse town they fancied, two artists who no one had yet heard of – again, there's that sense of excitement and discovery. Hunt had gone through Auckland University and White was taught at Elam. But they were more importantly and enduringly educated by each other. Their friendship reads as such a fine romance. What would it really have been like to be there, to be part of the scene? Beer in crates, Dylan (Hunt's lyrical muse) and Rod Stewart (Hunt's vocal muse) on the stereo, $8 in a savings bank…At the end of 1971, White "packed her belongings, put the cat on the back seat and caught the ferry to Lyttelton, en route to Dunedin." The Paremata years were over. New Zealand culture was on its way.

Robin White: Something is Happening Here edited by Sarah Farrar, Jill Trevelyan and Nina Tonga (Te Papa Press and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, $70) is available in bookstores nationwide. ReadingRoom is devoting all week to this beautiful book. Tomorrow: Justin Paton on her classic image of a fish and chip shop.

A major retrospective exhibition featuring more than 70 works from across White’s 50-year career is currently showing at Te Papa, followed by Auckland Art Gallery in late October.