The leadership of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) sounded an optimistic note in summer 2021. The pandemic, the agency said, had a silver lining for the 117-mile rail transit system, which crisscrosses Washington, D.C., and reaches into the neighboring states of Maryland and Virginia.

Radically reduced demand, it continued, meant WMATA could prioritize much-needed maintenance without crippling service disruptions. A steady flow of capital subsidies approved before the pandemic, coupled with emergency federal relief, meant the agency should have the resources to get the job done.

"The region's investment is paying dividends to our customers who are getting better service," said Metro's then–General Manager Paul Wiedefeld in an August 2021 press release. "Riders who are returning for the first time since the pandemic will see a more reliable train service than we've offered in years."

The headline of an equally optimistic Governing article on October 8, 2021, declared, "D.C. Metro: Once Off the Rails, Now Back On."

Four days after the Governing article was published, a Blue Line train derailed outside the Rosslyn station in Northern Virginia. A preliminary investigation pinned the accident on wheel alignment issues with Metro's brand new 7000-series trains. Regulators said that Metrorail staff knew about the issue for years but had failed to act on the problem. A few days later, safety officials ordered all the 7000-series cars, about 60 percent of Metro's fleet, removed from the tracks.

Metro was back off the rails again.

Wait times for trains, typically somewhere between five and 15 minutes depending on the line, often became 30 minutes in the immediate aftermath of the 7000-series' removal. Ridership plummeted to 1970s levels, when Metro first opened. With fewer trains in service, the cars that were still operating were often overcrowded.

As of October 2022, most of those 7000-series cars remain mothballed; long wait times continue to frustrate the small crowd of remaining riders. Officials kept promising a return to normal order, and kept delaying that return. No one could authoritatively say when the third-largest heavy rail system in the country would be back on track.

Public transportation has an inherently difficult road to travel in America. The speed and convenience of auto travel mean that most people who can afford to drive do. Low-density zoning near transit stations means fewer people live near them, leading to fewer riders. Funding arrangements that prioritize expansion over maintaining existing lines have left many systems with giant, service-disrupting maintenance backlogs. Buy American provisions, union work rules, and environmental review have helped make fixing anything, or adding new capacity, absurdly expensive.

Even so, D.C.'s main transit agency is uniquely prone to disaster.

"WMATA has these weird problems that no other transit agency, or even no other government, has," says Baruch Feigenbaum, a transportation researcher at Reason Foundation, the nonprofit that publishes this magazine.

The problems start at the top. WMATA's large, unwieldy board of directors requires consensus to make major decisions, but it is internally divided between representatives of the three local jurisdictions the agency serves. Instead of providing effective oversight or setting strategic priorities, it often busies itself in day-to-day operations better left to professional staff.

That professional staff, meanwhile, has been criticized again and again—in congressional hearings, post-accident investigations, and press reports—for a culture that prioritizes avoiding blame over achieving safety and smooth operations. Avoidable, service-disrupting issues continue to go unaddressed.

These internal problems have been exacerbated by a pandemic-era rise in remote work, costing the agency huge amounts of fare revenue.

Even the most well-oiled transit agency would struggle to respond to a pandemic that wrecked public transit ridership across the country—and few would describe WMATA as well-oiled. The agency has a culture of dysfunction and disregard for the fundamentals of safety and passenger service, a culture that has persisted even as it has attempted reforms. Metro's problems aren't going anywhere.

Board Games

In early 2017, Fivesquares Development was in the final stages of negotiations to turn a WMATA-owned surface parking lot at the Grosvenor-Strathmore station in Montgomery County, Maryland, into a mixed-use apartment and retail development. To test out potential retailers for the project, Fivesquares wanted to host some pop-up stands that would sell food, drink, and flowers right in front of the station.

Metro staff supported the idea. But WMATA's eight member Board of Directors—composed of two directors each from Maryland, Virginia, D.C., and the federal government—had to weigh in.

In February, the board approved Fivesquares' plan for a few afternoon shops outside the Grosvenor-Strathmore station.

In April 2017, Fivesquares and Metro staff were back in front of the board with a different type of request: to let the developer install a piece of loaned public art at the station's entrance. In September, they were asking the board if they could install another piece of art at the station.

These were approved too. What's striking here isn't how the board reacted to the requests. It's that it was required to consider them in the first place.

There's a lot of variation between the boards of directors that oversee the nation's local transit agencies, ranging from how many members they have to how they're selected. A common feature is that they function as policy-setting bodies that establish long-term goals and priorities for the system. It's then left to the agency's full-time employees to implement those goals and run day-to-day operations.

That's not the case with the WMATA board, which is deeply involved in seemingly minor decisions about Metro operations—including whether to let a developer place a piece of loaned artwork at its own expense in front of a retail operation the board had already approved. In most other transit agencies, this would be a decision made by professional staff overseen by a CEO or general manager. But WMATA's professional leadership is remarkably weak.

"Everything goes to the board, and through the board. The managerial discretion reserved to the general manager is unusually limited," says Jonathan L. Gifford, a professor at George Mason University's Schar School of Policy and Government, who says this level of micromanagement creates an incredibly rigid and inflexible organization.

The general manager serves as the chief administering officer. But WMATA's founding documents are largely mute about what his or her precise role and powers should be.

The 1967 interstate compact that created WMATA—agreed to by D.C., Maryland, and Virginia and blessed by Congress—mentions the general manager only eight times. The board of directors receives 233 mentions.

And while WMATA's board is uniquely invested in day-to-day operations, its decision-making process is also uniquely cumbersome and divisive.

Its bylaws require that most of its decisions receive both support from a majority of the board and support from at least one of the two directors appointed by each participating jurisdiction. This can cause conflict, given these different entities' often-divergent interests. Representatives from Maryland and Virginia are focused on maintaining rush hour service for their suburban commuters. D.C.'s representatives want longer service hours and low fares for the city's off-peak and lower-income riders. And they all want to limit their own financial contributions to the system.

"It's very hard to make decisions that favor the region, if the district, Virginia, Maryland, or the federal government is going to be adversely affected by it," says Gifford.

Sensible decisions with majority support can be derailed by opposition from one of these parties. That in turn can cause board meltdowns whenever hard decisions involving unpleasant tradeoffs need to be made.

Consider a moment in 2015, when the board was wrestling with how best to shore up WMATA's constantly imperiled fiscal situation. One idea floated was to raise fares to help cover the gap. A majority of the board said they'd at least consider that proposal. But D.C.'s directors, including then-Chairman Jack Evans, came out flatly against it. Their threat of a veto was enough to kill off fare increases.

Then, when Evans proposed spending additional money to pay down WMATA's unfunded pension obligations—another idea that had majority support—Maryland's directors vetoed it. When Evans complained at the board meeting that vetoes shouldn't be used so lightly, a smiling Maryland director, Michael Goldman, reportedly held up a sheet of paper reminding Evans that D.C. was the last jurisdiction to exercise its veto over a land use.

These problems are compounded by the board's lack of transparency. Critics contend that the press and other outside watchdogs are given little access to information and that the public (and riders) aren't given the opportunity to provide meaningful feedback. The agency is notorious for rejecting records requests on the flimsiest of grounds. Media outlets have had to resort to lawsuits to get basic information.

That opacity, in turn, has allowed corruption to fester.

In June 2019, Evans, still board chair as well as a D.C. councilmember, was the subject of an ethics probe into potentially inappropriate dealings he'd had with vendors looking to do business with WMATA. The board hired an outside law firm to investigate Evans' behavior, and the board's ethics committee held a hearing where its findings were discussed.

Bizarrely, the hearing was closed to the public. No written minutes were produced. Other than soliciting an agreement from Evans that he wouldn't run for board chair again, the committee took no action. It also refused to release the law firm's investigation.

That produced the odd result of Evans declaring that he had been found innocent of any wrongdoing while other directors said he'd violated at least some of the board's rules.

Only under pressure from Maryland's and Virginia's governors did WMATA eventually release the findings of the outside law firm. The 20-page audit had in fact found that Evans misused his position to drum up business for clients of his consulting business while punishing its competitors.

Evans was forced to resign a day later. A day after that, the FBI raided his house.

WMATA's poor board governance and weak general management, in turn, mean that no one really has the power or ability to take on a toxic work culture within WMATA itself that degrades service and puts riders at risk.

A Cultural Problem

The wheel-alignment issue that caused the major Blue Line derailment last year and forced hundreds of other cars out of service was a surprise to everyone—except Metro staff.

At a press conference a few days after the derailment, National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Chair Jennifer Homendy said WMATA knew about this defect as far back as 2017 and that it had attributed a mounting number of derailments to it over the years.

But agency staff did not inform the independent safety regulators at the Washington Metrorail Safety Commission (WMSC) of the issue. Nor did it tell the WMATA Board of Directors. Instead, they let it worsen until the 2021 incident—which Homendy described as potentially "catastrophic"—prompted intervention from outside regulators.

WMSC CEO David Mayer told Maryland legislators in June that issues with the 7000-series trains weren't so much engineering problems as "a people and culture kind of thing. It's a procedures kind of thing."

This wasn't a new assessment.

WMATA's unwieldy and divided board has had a difficult time setting priorities, making hard tradeoffs, and following through on a strategic vision for the system. The board has also earned criticism for letting a culture of noncompliance and disregard for safety fester at the agency it oversees.

Despite repeated efforts at changing that culture from outside and from above, the same problems keep turning up over and over again.

The deadliest accident in WMATA's history occurred in 2009, when two Red Line trains collided outside the Fort Totten station in Northeast D.C., killing nine people and sending another 52 to the hospital.

The immediate cause of the collision was a defective track circuit that failed to report the presence of an idling train at the station to an incoming train's automatic control system, preventing it from stopping. A major contributing factor to the crash, according to an NTSB report on the incident, was "WMATA's lack of a safety culture."

The subsequent investigation revealed that the same track circuit issue had caused near-collisions years before. WMATA staff had come up with a maintenance procedure to detect the problem, but technicians were never told about it.

In the wake of the Fort Totten crash, the NTSB made a long list of proposed improvements to WMATA, including a better reporting system for safety hazards, better internal communication about those hazards, and the adoption and adherence to formal maintenance checklists and procedures.

Under a new general manager, the agency adopted many of the NTSB recommendations and initiated a $6 billion capital program to shore up the system.

It didn't help.

In 2015, an electrical problem with the third rail caused a train to fill with smoke. A series of errors at Metro's rail control center left that train stuck in the smoke-filled tunnel near L'Enfant Plaza. One woman was killed, and nearly 100 people were injured.

Though the technical issue was different, the post-accident investigation again blamed Metro's poor safety culture. A scathing NTSB report said the incident proved that WMATA's cultural problems were too intractable for the agency to fix on its own. It issued an urgent recommendation for federal authorities to take over safety regulation of the system.

The Federal Transit Administration did take over regulatory control of Metrorail in October 2015. Two years later, Maryland, Virginia, and D.C. agreed to establish the WMSC as an independent safety oversight board with the power to order WMATA to stop service and adopt changes.

Additional oversight was complemented by changes at the agency. In response to a track fire in March 2016, Wiedefeld, just a few months into the job as general manager, shut the system down for an entire day to do emergency inspections. A few weeks later, he launched the ambitious SafeTrack program. This made some progress in bringing Metro tracks back into a good state of repair but created major disruptions in service.

Nevertheless, the same problems kept popping up.

WMATA's response to a fire on its Red Line in December 2019 bore "striking similarities" to its response to the L'Enfant Plaza incident, including a chaotic control room where operators shouted over each other and failed to follow established disaster response checklists, according to a WMSC incident report.

A 2020 report from the WMSC on WMATA's rail operations control center described the culture as "toxic and antithetical to safety."

The debacle over the 7000-series trains prompted Wiedefeld to announce in January 2022 that he would retire as WMATA's general manager in June. He wouldn't even last that long.

In May, the agency announced that half of its 500 rail operators hadn't gone through required recertification trainings; 72 of the most delinquent operators would be taken off active duty until their training was complete. This produced a staffing shortage. Wait times for trains increased.

Like so many of its issues, lapses in recertifications were nothing new for WMATA. The Federal Transit Administration had identified this problem all the way back in 2015. In response to the scandal, Wiedefeld said he'd leave a month early. WMATA's chief operating officer also resigned.

It was an ignoble end for a general manager who had built up a reputation as a reformer willing to make the hard decisions necessary to get Metro back on track. And the troubles he left behind at the agency have been made worse by the biggest external shock it ever faced.

Remotely Working

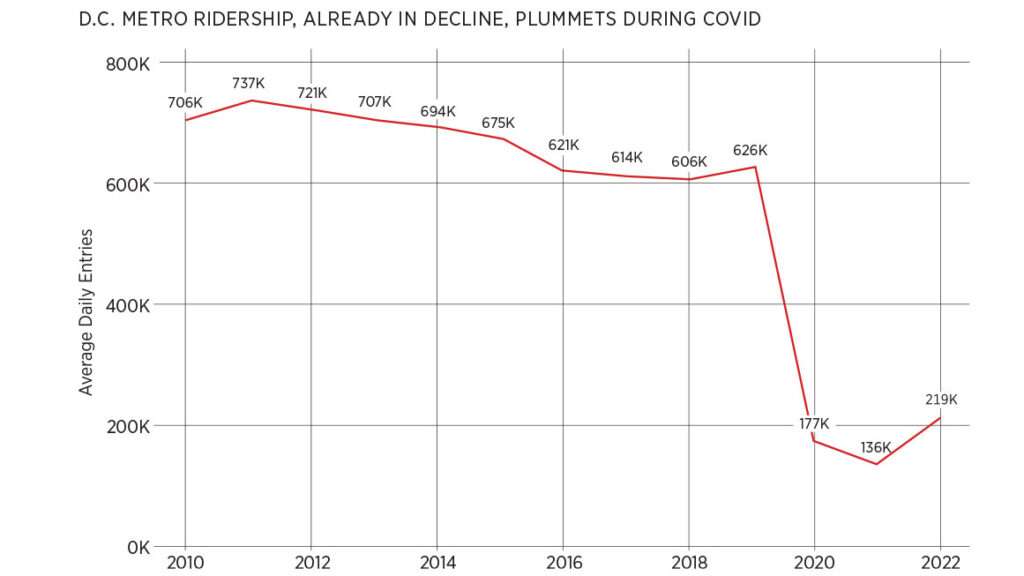

The sudden onset of COVID-19 in early 2020 and the lockdowns and social distancing that came with it saw a sudden spike in remote work across the country. Commuting numbers collapsed across all modes of transportation. The metro area's famously congested Beltway quickly emptied. The drop in public transit ridership was even more dramatic. Metrorail averaged roughly 639,000 daily boardings in 2019. In 2021, ridership dropped to 177,000 daily boardings.

The sudden disappearance of those riders' fares blew a hole in every transit agency's budget, and WMATA was no exception. In 2019, the agency was able to cover nearly two-thirds of its rail operating budget with fares, parking fees, advertising, and the like. By fiscal year 2021, the cost recovery ratio for its rail service had dropped to just 14 percent.

Metro leadership warned that there would be big service cuts, station closures, and staff layoffs unless it got a lot of federal aid.

It all sounded dire. But the pandemic also presented Metro with an opportunity.

For starters, the federal largess proved forthcoming. Three rounds of bailouts, totaling $2.4 billion, plugged the COVID-sized holes in WMATA's operating budget. The drop-off in ridership and service also meant that Metro could accelerate its schedule of much-needed repairs. That, officials reasoned, would improve service quality by the time everyone was ready to come back to the office.

For a while it looked like that sunny scenario was playing out. In August 2021, Metro released a report detailing the progress it had made replacing electric cables and track insulators, rebuilding more train platforms and bus facilities, and improving stations with new faregates and lighting.

This produced some tangible results, including a falling number of track fires. But the rush of returning commuters never ended up happening.

One major reason for this is that remote work proved a far stickier arrangement than most people had predicted. Freed from a daily commute, many employees had no interest in coming back to the office on a regular basis. Many employers weren't eager, or able, to force their return.

Nationwide, according to surveys by WFH Research, workers who could be remote spent 2.2 days working from home by summer 2022. That matches with office occupancy data in the country's largest cities, which show offices only about half-full in the largest downtowns. The pandemic also kicked off a wave of migration from cities to suburbs, where people are farther from the office and from the transit that might take them there.

These trends were particularly acute in the D.C. metro region. An Ernst & Young analysis estimates the area has the second-most "remote-capable" workers in the country, behind only San Francisco. The region's office occupancy rate has hovered at around 45 percent for most of 2022.

Spidery rail transit systems like WMATA, with long branches converging from the suburbs into downtown D.C., were built with suburban-to-city commuters in mind. Metro doubled down on this setup with a pricing strategy that charged higher fares during peak hours and for longer trips.

That model has been especially vulnerable to the post-COVID slump in office work.

"Metrorail fares collected during the typical commuting hours generate the largest share of revenue for Metro," Wiedefeld testified to Congress in February 2022. "With that ridership gone, we are seeing a more severe impact on revenues than our sister agencies in other regions." As of May 2022, weekday ridership is only about 35 percent of where it was at the same time in 2019.

But WMATA isn't wholly a victim of circumstance.

Going to work isn't the only, or even the primary, reason people make trips outside the home. We go all sorts of places throughout the day, whether that's running a quick errand, having an impromptu meeting with a friend, or heading to a ballgame. In theory, Metro could fill the void left by office commuters by servicing those kinds of trips instead. But the recent self-inflicted drop-off in service frequency has made Metro the least convenient option for off-peak trips.

Death Spiral?

The struggles of American public transportation have sparked some commenters' musings about a "transit death spiral" where declining service leads to falling ridership and less revenue. Agencies respond by raising fares and cutting service to fill the fiscal hole, which sends more riders fleeing. Repeat that cycle a few times, and there's not much of a transit system left.

This is essentially where WMATA finds itself after the pandemic. Ridership and service are already near rock-bottom levels. The agency reports that it faces a $356 million fiscal gap in the upcoming fiscal year, which it says will prompt service cuts, staff layoffs, and fare hikes.

This has sparked predictable calls for more federal aid and more local subsidies. Critics counter that dumping more money into an inherently dysfunctional institution won't fix WMATA's problems.

"The problem with money is it allows them to delay needed reform," says Feigenbaum. "It's not a solution for anything. It needs to come with a stick."

He suggests a first step would be to create a smaller, more independent board more focused on metrics and less beholden to the politicians that appoint its members. Privatizing the operations of WMATA would be another potential option, albeit a politically impractical one. And even a privately managed Metro system would still require massive government subsidies.

A similar idea to create a temporary five-person "reform board" was floated in 2017 by former U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, but it was eventually sunk by representatives from Virginia and Maryland who openly worried about their loss of influence over WMATA. (A 2018 reform did limit the ability of the board's eight nonvoting alternate members to participate in committee hearings.)

A smaller, more focused board could, alongside the relatively new WMSC, provide more effective oversight and identify potential issues before they become service-disrupting disasters. A less political governing body might be more willing to entertain more sweeping changes to WMATA's operations. Expanding bus service, for example, would help the agency perform more trips to more locations, better matching post-pandemic travel demands, and it could be done without massive capital investments needed for new tracks and stations. It would also make the system less dependent on the persistently dysfunctional rail operations control center.

In the short term, at least, service is only set to get worse. In September, WMATA shut down its Yellow Line for at least eight weeks for repairs. Portions of the line will stay shut down until May 2023, as Metro rehabilitates the rail bridge that connects the Yellow Line's Virginia stops to D.C.'s L'Enfant Plaza. Even if the work is completed on time, it will be Metro's longest shutdown.

Elected representatives aren't yet willing to give up on WMATA. But they are increasingly open about their impression that the agency isn't even trying to fulfill its mission anymore.

"We have found what plagues WMATA is a culture of mediocrity," said Rep. Gerry Connolly (D–Va.) at a House Committee on Oversight and Reform hearing on WMATA earlier this year. "As the system has jumped from crisis to crisis, this culture of mediocrity has been a common theme."

At the same hearing, Connolly insisted that the "failure of WMATA is not an option." The disaster-packed recent history of the system strongly suggests that it is.

The post Pandemic Repairs Were Supposed To Put D.C. Metro Back on Track. Then It Literally Went Off the Rails. appeared first on Reason.com.