The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing systemic inequities. It’s also presented new hardships for marginalized families and under-resourced communities associated with loss of income, lack of access to social support services, increased care responsibilities and a rise in depression and anxiety.

Learning loss has become a buzz word since the onset of the pandemic, referring to general loss of knowledge and skills due to education disruptions.

Ontario standardized testing

Ontario introduced standardized tests administered by the Education Accountability and Quality Office (EQAO) in grades 3, 6, 9 and 10 to hold the education system accountable for promised education quality. EQAO was established in 1996 as an arms-length government agency and costs about $33 million annually to administer.

Many teacher unions, educators and parents oppose the testing. They argue that it doesn’t fulfil its mandate, has led to a narrow measure of student achievement and contributes to fear of failure.

As my book Decolonizing Educational Assessment Ontario Elementary Students and the EQAO explores, the administration of the current model of EQAO is based on false assumptions that standardized tests accurately and objectively capture student achievement levels.

Equity lens

NDP and Liberal election positions on revisiting the EQAO reflected findings from a 2018 report led by six expert researchers who, at the time, were Ontario’s education advisers to the provincial government.

Part of their concern was that while assessments like EQAO identify how students are doing, they tell us little about how students may have gotten there or why they are underachieving.

It’s important that Ontario’s new government engages in community discussions about the validity of EQAO testing and other aspects of schooling that affect student achievement.

Barriers in opportunities

Since EQAO testing was introduced in Ontario, achievement gaps across different social groups and communities have not drastically reduced and have instead further widened. Widening gaps pertain to students with special education needs, students who are English language learners and across race and socio-economic status in comparison to non-racialized students and higher socio-economic communities.

EQAO does not currently collect race-based data. But data from the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) — one of the largest boards in North America — show Black and Indigenous students have been more likely to be streamed into non-academic programs than white students. Black, Indigenous and some groups of racialized students have been disproportionately expelled from TDSB schools.

Read more: Ending ‘streaming’ is only the first step to dismantling systemic racism in Ontario schools

The data show worse school achievement for Black and racialized students: For example, 57 per cent of TDSB students are at the provincial standard, according to the Grade 9 2018 EQAO mathematics assessment, compared to 18 per cent for Black students. This achievement gap is due to opportunity gaps — the intersection of systemic inequities that create barriers for students to access and secure opportunities to achieve their full potential.

Focusing on achievement gaps prioritizes differences in outcomes as the barometer for identifying education inequities. Focusing on opportunity gaps provides a more holistic community lens beyond individual student outcomes. This focus allows us to to examine systemic inequities that serve as barriers impacting student achievement.

The Fraser Institute think tank ranks schools annually based on EQAO results over a five-year period. These rankings have gained so much currency that they influence property values.

Although the Fraser Institute rankings specify the percentage of English as a Second Language learners and students with special needs, they don’t capture the systemic barriers impacting school communities.

Closing achievement gaps: Alternative approaches

Even if the province revamps assessment, what won’t help is pressuring teachers to devote more time to preparing students for tests. What’s needed is alternative approaches to meeting local community needs.

One example is the Youth Association for Academics, Athletics and Character Education (YAAACE).

This community organization seeks to close the achievement gap for students living in the Jane and Finch Community in Toronto. It was founded in 2007 by Devon Jones, an educator with the TDSB and a local community activist.

YAAACE focuses on creating access to opportunities for community residents by mitigating the risk factors that keep students and families from achieving their full potential. It prioritizes providing continuity of care through year-round affordable and accessible programming.

For example, YAAACE aims to ensure students have access to a caring adult at all times in a 24-hour cycle, particularly outside of school hours, on weekday evenings and weekends — when they may be exposed to risks.

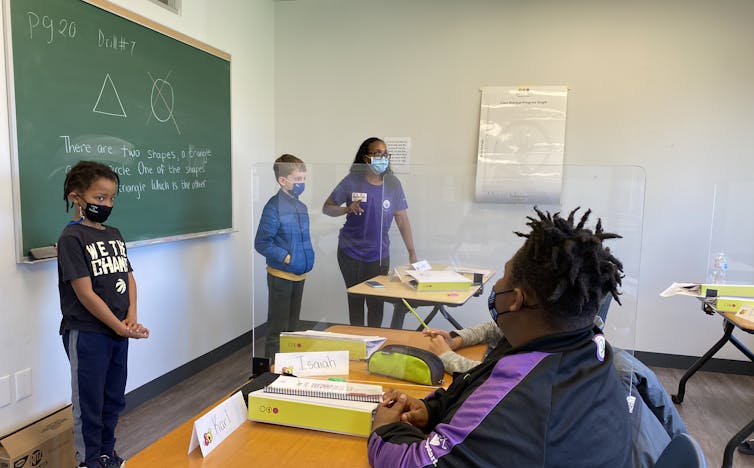

YAAACE offered an evening and weekend supplementary academic program between September 2020 to May 2021 in partnership with Spirit of Math, an after-school math enrichment program. The Community School Initiative offered a structured math curriculum to students in grades 2 to 8 at a subsidized cost.

A team of caring adults, including coaches and Ontario certified teachers supported this program. A final February 2022 report shares how the Community School Initiative created access to academic opportunities that were affordable and socio-culturally relevant, and minimized achievement gaps by mitigating opportunity gaps.

Narrowing inequities

No one is arguing that the province shouldn’t seek to collect data pertaining to effective schooling. But governments need to consider how it can be collected more effectively in partnerships with school boards, educators and community agencies to better support the local needs of students and their families.

This requires a policy and practice shift to an equity lens. We need to invest in programs and policies that view education as symbiotic with the larger community.

Devon Jones, the founding director of YAAACE, and Tamasha Grant, YAAACE’s public safety consultant, co-authored this article.

Ardavan Eizadirad receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.