It might not have been the medal he had hoped for, but with silver around his neck, Dan Bigham acted out the denouement of one of cycling's most inspiring stories, one that almost saw the curtain come down early.

There was a moment last Friday when the 32-year-old feared his Olympic dream was over. It happened in an open training session, inside the Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines velodrome on a sunny morning. Bigham had gone eight years without crashing on the track, until he swung up in a team pursuit change, and collided with another rider who was rolling around higher up the boards. Both fell hard and slid down onto the apron.

"It was about five metres away there," Bigham recalled, pointing to the banking, moments after winning silver in the team pursuit. "I was in a lot of pain thinking, simply put, I fucked it. I crashed at 65km/h, my shoulder was not in a great way. Thankfully, I didn't break any bones, but my biggest thought was that I've let these guys down."

In the days after, he said, movement became a struggle. Simply lifting his arm to brush his teeth had him wincing in pain. He turned up to qualifying on Monday with a bandage over his right shoulder, and was helped into his skinsuit by a member of the team's staff. He then sat out of the first round against Denmark, before returning to the quartet in the final – alongside Ethan Hayter, Ethan Vernon and Charlie Tanfield – where he dug deep, fought through the pain, and took the Australians down to the wire.

"I was the most nervous I've ever been," he said. "The start was a big factor. Basically, I've got a lot of pain through the joint, I've done some damage to it, and starting really hurts. I threw myself out of the gates as hard as I could, and had a great start."

As the effort went on, though, he said the injury "cost performance". "I can't lie. I wasn't my absolute best today. I wasn't my absolute best ever since the crash, and that's frustrating, for sure," Bigham said.

"Yes, we can't stand on the top step and say we're Olympic champions and everything that goes with that, but it's absolutely no regrets of how we've gone about it. It's been a pretty epic few years."

For Bigham in particular, the path to the Olympics has been a winding one, a dream that at many points seemed impossible.

A master's graduate in motorsport engineering, the Brit became famous in cycling circles for his aerodynamics knowledge and focus on innovation. He first entered the national team fold in 2018, when he raced the individual pursuit at the Track World Championships, but when discussions took place about getting onto the Olympic programme afterwards, he was told he would have to choose between being an engineer or a rider. He decided to pursue both, away from British Cycling.

Until recently, Bigham's cycling career had been one side of a double life, the side he does for free. He has always made his living in other jobs, and still only 32, has an enviable and wide-reaching CV; He worked in Formula 1 for Mercedes, started his own aero products business called Wattshop, wrote a book on reverse engineering in sport and, over the past few years, has worked as a performance engineer for WorldTour team Ineos Grenadiers.

At the same time, he's dedicated himself to cycling. When he parted ways with British Cycling in 2018, he made it his mission to beat the national squad in a team pursuit, and did so with a group of his friends in HUUB-Wattbike, coached by Mehdi Kordi, who now heads up the Dutch sprint squad.

"When he came onto the scene, everyone, particularly in the national set-up, was talking about how the whole game was going to catch up with him," Kordi told Cycling Weekly. "[They said] his engineering advantage would be taken away from him, and he was just going to go back to being a nobody. In the end, he's turned out to be one of the best British pursuiters we've ever had."

Bigham has since become a world champion, a double European champion, holder of the World Hour Record, and now an Olympic silver medallist.

"Rather than people catching up with the engineering, he caught up with people's physiology," Kordi said. "He's trained hard and he's earned his spot. As someone who worked with him before, and as a friend, I watch him with immense pride."

Since the early days, as he went from competition to competition, Bigham was always generous with his ideas. He'd watch other riders inside the velodrome, those he was racing against, and offer them tips on how they could go faster. For the Tokyo Olympics, he took up a job with the Danish team pursuit squad, and helped engineer their way to a silver medal.

In training, he'd slot in with the Danish quartet, and once rode a sub-3:50 effort, becoming the first British rider to do so. "I thought that was the pinnacle of my career," he told the BBC. More was still to come.

"When I first got to know him, all we talked about was going to the Olympics," Kordi said. "As you can imagine, HUUB-Wattbike was a vehicle to at least get them into the set-up and go from there. It may have, at least, gone to the back of his mind, but he and the rest of the team definitely talked about the Olympics."

Now, Bigham is an Olympian. He's also a professional cyclist for the first time in his life, having taken three months unpaid leave from Ineos, and picked up a short-term athlete grant to fund his Paris campaign.

"I think it's one of cycling's…" Kordi began, before correcting himself, "one of sport's great stories, for a number of reasons. Number one, in this day and age, he's an amateur. For some people, they scoff at that idea. They go, 'Yeah, but he's got a job in cycling and this and that.' The definition of an amateur is that you don't do that craft for a living, and he doesn't. He gets his money elsewhere. He is, by definition, the last amateur, in my opinion, in professional sport.

"He's the embodiment of what the sport is. He's very open with his ideas, he shares, and if he takes a loss, he holds his hand up and just goes, 'I wasn't fast enough.' They're all admirable qualities."

True to his character, that's what Bigham did after the team pursuit in Paris. With his teammates standing in earshot, he told the press that his injury "could have been the difference between gold and silver today", a thought that was quickly swatted away.

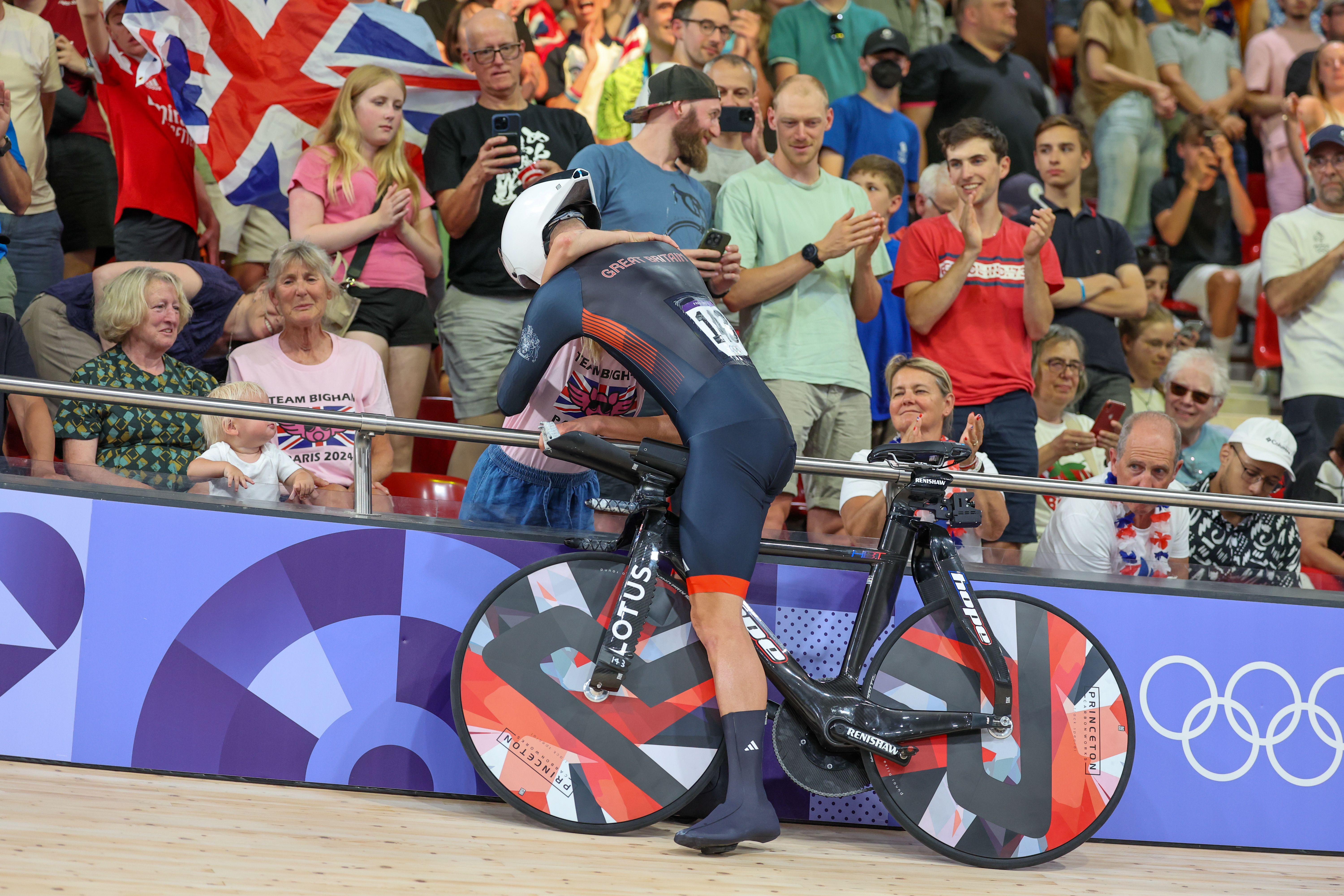

He then strolled through the media zone, the last of his teammates to leave, smiling and soaking in his first, and likely last Olympic experience. It was a life-long dream accomplished, one that was so almost derailed days before, but ended with him pulling up along the banking, hugging his wife, Joss Lowden, herself a former Hour Record holder, and sharing a moment with their son, as an Olympic silver medallist.

How does he reflect on his journey? "I've been asked that question in different forms many times," Bigham said. "I think a lot of things, really, justifications to the decisions I've made. I've been criticised, I've been lauded for things.

"I just think in general it has been an awesome journey, and a story that I'm very pleased with even more so since becoming a father. I want to be able to hopefully, one day, tell my son and just be proud of it."