Daniel Bard recognized the knot in his stomach. He recognized the racing mind that kept him awake at night. He recognized the tension in his muscles as he drove to the ballpark before games. And he knew these symptoms all stemmed from a feeling he was all too familiar with: the sudden inability to throw a baseball where he wanted.

He recognized it all from more than a decade ago, when an extremely public bout with the yips sent him searching for answers for seven years. It was like stumbling around in a dark room, groping desperately for the exit. At times, as yet another hypnotist met him in yet another poorly lit Holiday Inn, hiding because he was so ashamed of what he then called a failure, it felt “like drug deals,” says his wife, Adair. “Like illegal activity.”

But he found his way out, reinvigorating his career as the Rockies’ closer, even earning National League Most Valuable Player votes last season, and Adair had just begun to watch games without a knot in her own stomach when he reported for Team USA in the World Baseball Classic in March, and everything came apart again.

After the worst outing, the one when he threw 17 pitches, recorded zero outs, allowed four runs, walked two and broke the right thumb of Venezuela and Astros second baseman Jose Altuve, Adair hopefully asked Daniel whether there might be an innocent explanation: a slick ball, perhaps.

“Nope,” he said. “Definitely felt a little yippy.”

Most baseball men call the sport’s most mysterious ailment the monster or the thing, as if calling it by its name might summon it, so it was unusual that Bard spoke the word aloud. Even more unusual—and what just might make him the most remarkable story of this baseball season—was what he did next.

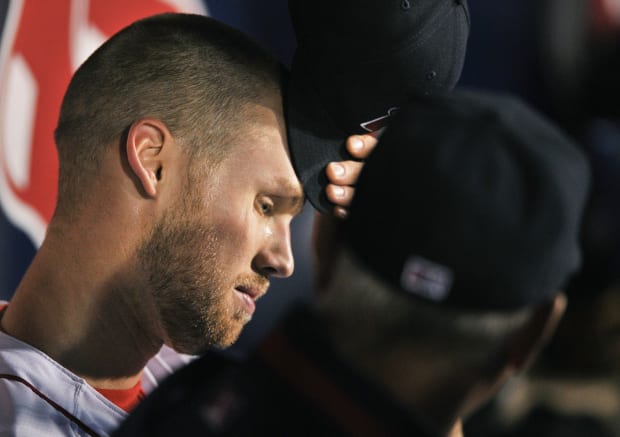

Justin Edmonds/Getty Images

What people think of the first time was actually the second time. Bard, now 37, arrived at Red Sox camp in 2007 as a first-round pick who threw 100 mph almost without effort as a starter, but Boston coaches shifted his arm slot higher.

“I got really aware of my movement,” Bard says. “Nothing was free and easy like it had been my whole life.”

He walked 22 batters and hit one in 13⅓ innings at High A Lancaster, then walked 56 and hit seven in 61⅔ at Class A Greenville. Six weeks pitching out of the bullpen for the Honolulu Sharks in winter ball helped, as did Double A pitching coach Mike Cather, who accompanied him there, lowered his arm slot and encouraged him to think less. Cather simplified Bard’s repertoire and played long toss with him until his arm hurt and his mind cleared. In 2009, Bard made his major league debut as a reliever.

That season, he threw a pitch to strike out the Yankees’ Nick Swisher that defied classification and the laws of physics: 99 mph with changeup movement, almost like a reverse slider. In 2010 and most of ’11, Bard was the most unhittable pitcher in the sport. So when he could not find the strike zone in September ’11, he was surprised. He later learned he was suffering from an undiagnosed case of thoracic outlet syndrome, a compression of the nerves or blood vessels in the space between the neck and the first rib. But the next spring, Red Sox coaches decided to stretch him out as a starter and began tinkering again with his mechanics. The physical problem turned into a mental one.

After he walked 37 batters and hit eight in 55 major league innings, Boston sent him down to Triple A, whereupon he walked 29 and hit 10 in 32 innings. In 2013, when he walked 29 in just 16⅓ innings across three minor league levels and the majors, he stopped referring to his ailment as “a throwing problem” and Googled “how to get rid of the yips.”

He tried almost everything. He threw sidearm. He threw submarine. He began tapping, a therapy in which a patient touches pressure points while talking through trauma. He lifted weights until he nearly collapsed. He gulped beer before bullpen sessions. He met with three different hypnotists. He can see now that he did not give talk therapy much of a chance, in part because he did not want to admit to anyone else that the root of the problem was mental—but mostly because he did not want to admit it to himself. So he adjusted his delivery and did his tapping and his lifting and his drinking and his hypnosis, and he did not talk about how scared he felt.

The whole way, his arm felt fine. He wondered whether he had a brain tumor.

The Red Sox designated him for assignment after 2013. He flew to Caguas, Puerto Rico, for winter ball, where he pitched in three games, got one out, walked nine and hit three. He signed with the Rangers in ’14: four games at Class A, two outs, nine walks, seven hit batsmen. He signed with the Cubs in ’15 and never even made it past drills. He signed with the Cardinals in ’16: eight games at High A, nine outs, 13 walks, five hit batsmen; 10 games at Double A the next year, 26 outs, 19 walks, two hit batsmen. When they released him in May ’17, he signed with the Mets: one game in rookie ball, two outs, five walks, two hit batsmen. His opponents were teenagers. He was 32.

Finally, in August of that year, he finished a bullpen at the Mets’ spring training facility in Port St. Lucie, Fla., and thought about his 18-month-old son, Davis, at home in Charlotte with Adair. He had spent the past year and a half with Davis as “my main why,” he says, trying to go about his work and interact with everyone he encountered in a way that might someday make his son proud. Now he just missed him. He went home.

Gabe Souza/Portland Press Herald/Getty Images

Bard surprised himself when he accepted an offer in 2018 to become the Diamondbacks’ mental skills coach. He wasn’t sure he wanted to be anywhere near baseball; as late as ’19, he was making up excuses not to play catch with Davis and his little brother, Sykes, rather than introduce them to something that had caused him so much pain. But as he had struggled, teams had demoted him to increasingly lower levels, meaning his teammates got younger as he got older. They began asking him how to throw a slider and how to know whether you’ve met the person you should marry. He cherished those relationships and thought maybe it would be nice to have them back.

And as he told his story again and again, he started to tell it differently. “Everyone was like, ‘Oh, what happened? I remember you in Boston,’” he says. “I’d tell the story of what happened, and I was embarrassed about how my career ended. I viewed my career as a big failure. But the reaction was either of two things: Either, ‘Man, you got to play four years in Boston!’—these are a lot of Double A, Triple A guys who had no big league time—‘I’d give my left arm to play one year in Boston; you got four.’ If you look at it that way, it’s pretty cool. Or they’d be like, ‘Wow, you grinded through that for five years? That’s unbelievable.’” He laughs and adds, “Or stupid. But the reaction—I started to view that part of my career in a different light.”

Meanwhile he wanted to build trust with young players, so he took them to the place they felt most comfortable—the field—and talked while playing catch. In 2019, relieved of the pressure that crushed him for the better part of a decade, he found that his throws went where they were supposed to.

Young pitchers enthusiastically encouraged him to make a comeback. He dismissed them for a while but eventually realized he was actually enjoying himself. He and Adair loved the idea that the kids—Davis, Sykes and then newborn daughter Campbell—might get to see him play. He spent the winter working out with his brother, Luke, then a righty for the Angels.

In February, Bard quit his job with Arizona. Five days later, he threw off a high school mound for 25 scouts. The Rockies signed him later that week. Midway through 2020 they installed him as their closer. Last July they signed him to a two-year, $19 million contract extension.

Maybe that’s where it started. “He was talking a lot about expectations” this spring, Adair says. She tried to remind him there were plenty of expectations last season, when he had a 1.79 ERA and 34 saves. But in four spring training outings, “My mechanics didn’t feel super locked in,” he says. “I didn’t feel that automatic freedom, how you want to feel on the mound, where all you’re doing is picking the pitch you’re gonna throw and everything else just happens.”

His four-seamer sat around 94 mph rather than the 99 he typically throws, but he could still throw strikes, so he figured he would come around.

“Normally you have 10 outings in meaningless games to work through it,” he says. “I got thrust after four [outings] into probably the biggest baseball stage of my life, in a place I really wanted to do well and was super excited to be a part of, in an environment that—those environments in the WBC were the coolest baseball environments I’ve ever been a part of, which makes me so mad that I didn’t do well.”

His first game for Team USA went single, wild pitch, double, hit by pitch, flyout, single, strikeout, walk, single. He pitched a scoreless inning three days later, but he still didn’t feel quite right. “Like the early spring ones,” he says. “A little off.” Then came the disaster against Venezuela.

“Somewhere in the middle there, I started to feel a different level of anxiety,” he says. “We’re accustomed to a certain level of stress, and a certain level of stress makes you better at everything in life. It’s a great driver, a great motivator, a great energizer, all those things. But there’s a point where stress becomes not debilitating but uncomfortable, and I could feel that happening.”

The U.S. had come back against Venezuela to advance to the semifinals, but Bard asked the coaches not to use him. He stayed with the team, but he didn’t want to hurt anyone else.

“I do think that decision to not pitch there, in those situations, was supremely important in allowing him to fix things,” Adair says. They had both experienced Red Sox–Yankees games before, but the crowd at the WBC was a “whole new decibel,” she says. “So I think he just knew that that scenario of high-pressure games, performing in front of people that you respect … I think he just knew that wasn’t going to fix it for sure, and was definitely not going to help in any way.”

They returned to Phoenix to resume spring training and tried to tamp down their anxiety. They had both spent so much time at minor league facilities there in extended spring training during their odyssey; the place itself seemed to offer a reminder at how dark their days could become.

Bard pitched twice with middling results but no improvement in his physical or mental comfort. The time crunch only added to his concern. I don’t feel right, he thought. And I have six days until the season starts.

“When you’re going good, you’re selecting a pitch—you and the catcher—you’re looking at a target and saying Go, and your body goes,” he says. “You might have one little simple cue, like, Load or Stay back or Drive it down or whatever, something really simple.

“When you’re off, you say Go, and it doesn’t go where it’s supposed to go. Maybe it’s two or three feet off. You throw a ball. Then you go, Oh, shoot, that missed high. O.K., how do we get it down? O.K., stay on the back side longer. And now you’re throwing the next pitch giving two or three instructions on how to get that ball lower than it was, which a lot of times it results in an overcorrection, because that analytical part of your brain is not supposed to be involved in throwing a baseball. That part’s supposed to be automatic.

“So it just basically creates some interference and usually makes things worse. You’re in a game trying to get people out, but you’re also thinking pitch to pitch about four or five or 10 different things that are gonna help make the next pitch better.”

He confided in Adair that going back out there didn’t seem to be helping. “You need to talk to someone,” she told him. She thought back to those seven years of anguish, when he tried to rewire his brain on his own.

“We can’t go down that road again,” she says. “We don’t have the time.”

Daniel agreed. “I knew as I was doing this that I was going to take a very different approach, knowing that I’ve felt that before and I just grinded through it, and it got worse and worse and worse,” he says. “And I think the more you go through it, and the more negative experiences you pile on top of each other, the harder it gets to dig out of it.”

So he spoke to the Rockies’ mental skills coach Doug Chadwick, then to head trainer Keith Dugger, then to pitching coach Darryl Scott and finally to manager Bud Black. No one was terribly surprised.

They had noticed Bard’s stiffness even before he left for the WBC, but they were careful about their next steps. “It is hard, right?” says Dugger, who in part because of his position and in part because of his personality is close with many players. “Because you don’t want to talk about this all the time. Because if you do address it, there’s self-doubt. You bring it onto this guy.” They had noticed his performance at the WBC. So they were relieved when he spoke up.

First, Dugger eliminated a physical injury. Then the group determined that what Bard needed was time. Two days before Opening Day, they agreed they would place Bard on the injured list. They knew what they wanted to do. Now they just had to decide what they wanted to say.

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

Players need an injury designation to hit the injured list. “Back tightness” was vague enough. “Arm fatigue” had the advantage of being true. But Dugger suggested another route.

“I think it might be good for you to have a clear conscience about going on the IL with anxiety,” he told Bard. That way Bard would not have to invent a timeline for his return, pretend to stagger around in pain or lie to the media—and his teammates. “That might be stressful in itself,” Dugger pointed out.

And there was another element. “I felt if he was just hiding behind it, then it’s kind of throwing away a lot of the work he’s put into it over the years,” Dugger says.

Daniel and Adair thought about it before he agreed to anything. They worried about the reaction, both because some people still think seeking help is a sign of weakness and because Daniel’s history made any such admission even more fraught. But once they thought about that for more than a second, they realized it didn’t make much sense.

“There’s still obviously the ‘tough it out’ mentality in all aspects of life, but if Daniel Bard hasn’t toughed s--- out, then I don’t know who has,” Adair says.

They also hoped that being honest might make some small difference in the lives of people they love—and of people they don’t know. They wanted to encourage others to be open about their own mental health.

And the culture around sports has changed. Major League Baseball has encouraged teams to put players who qualify on the injured list with anxiety; Tigers outfielder Austin Meadows and A’s reliever Trevor May would later do so. In honor of May, Mental Health Awareness Month, the Giants ordered a shipment of T-shirts bearing the phrase IT’S OKAY NOT TO BE OKAY.

So Bard agreed, and a few hours before the Rockies opened their season against the Padres on March 30, they made it official. As with any other injured list stint, a doctor delivered the formal diagnosis, and Dugger submitted the paperwork to MLB. Then the team announced the move—that Bard was placed on the 15-day IL due to anxiety.

“As hard as it was to make that decision to do it, to be public about it, hours after doing it I knew it was the right decision,” Bard says.

He estimates he received 100 supportive text messages. Adair says she has never gotten so much engagement around anything on social media as she did on the Instagram Story she posted with a link to the news.

“I think a lot of people see that he’s on the IL with anxiety [and think], He must be in a horrible place,” Bard says. “And some people might be in that situation. I wasn't in a horrible place. I was in a place where I felt like it was definitely going to affect my ability to do my job the way I needed to do it. I wasn’t going to be helping myself or the team by trying to grind through it.”

Still, now he needed to fix the physical manifestation of it. Again.

Bard was already the yips’ greatest vanquisher. Righty Steve Blass, second baseman Chuck Knoblauch, lefty Rick Ankiel—all had the condition and all were forced to retire or change positions. So were countless others whose names the public never learned, because they failed more quietly. Lefty Jon Lester lost the ability to throw to first base but retained his mastery of the strike zone, so after years of experimentation he finally just scrapped his pickoff move and let the catcher handle it. A few men have come down with mild forms of the yips and recovered before they could take full hold, including Rockies catcher Brian Serven. But no one but Bard has succumbed entirely, publicly, and then overcome it. And certainly no one else has done that twice.

Daniel and Adair both saw the worst-case scenario as another interminable quest through the darkness. Daniel realized within a week he would avoid that outcome. With the deadline pressure of Opening Day gone, he felt his mechanical stiffness begin to ease. He remained with the team, and the other Rockies reminded him he was still a part of it. His catch partner, Tyler Kinley, broke down video with him, identifying what Bard looked like when he was pitching well. Serven insisted on catching all of Bard’s bullpen sessions, even though the bullpen catchers were willing. When Serven had been called up the year earlier, Bard invited him to group dinners and asked earnestly how he was doing.

“He was there for me, and I just wanted to be there for him,” says Serven.

“I think those guys probably don’t know how much they helped,” says Bard.

He declines to be specific about what exactly he did mentally during that period, out of some combination of a desire for privacy and a concern that he’s giving away a Rockies competitive advantage, but he says, “I’ve used as many resources as I can.” That included talking about his problems.

“I talked to the therapist back [in the mid-2010s], and I remember not being fully honest with him, because I didn’t want to have a mental issue,” he says. “I wanted the therapist—which he did, eventually, after, like, 10 or so meetings—to say, ‘Well, you seem fully mentally healthy. You have this weird glitch that is a deeper neurological thing, and either it’s going to go away or it’s not.’ … I was, like, 27 years old. My ego—I needed that, like, O.K, everything’s fine, and I just have this little glitch and no one can explain it and it’s fine.

“I’ve realized now that just being more open, more honest, more vulnerable in those conversations really helps you get to—it doesn’t have to be some deep-seated childhood trauma. There can be, but I don’t think there has to be. Just talking through, like, ‘Throwing feels really weird right now,’ getting that stuff out on the table helps you process it. And I didn’t realize that back then.”

And he started feeling good on the mound again. He still struggled—still struggles—to regain his elite velocity. But his diminished stuff was competitive, which increased his confidence.

“It kind of blows my mind,” he says. “I’m not perfect right now. I don’t feel like I did last year. Last year was the best I’ve felt in my career—mechanically, mentally, all across the board. So I’m not there right now, to be honest. But it’s close enough where I can think clearly on the mound, and I know I can compete with the stuff that I have. And that’s enough.”

His bullpens kept getting better. After two weeks, the Rockies asked Bard whether he felt ready for a minor league rehab assignment. That caught him off guard—he’d thought he might need another month. “I had to talk myself into it,” he says with a laugh. “‘You’ve been throwing good!’” He and the team agreed that if it didn’t go well, he’d start the process again.

But … it did. One inning, 23 pitches, 17 strikes. He allowed a single to the Padres’ Fernando Tatis Jr., making his way back from a PED suspension, then whiffed the next three batters. Three days later, the Rockies activated him. Since his season debut April 19, he has pitched 7⅓ innings with five hits, five walks and five strikeouts.

He knows as well as anyone how tenuous this can all be. But he also believes going through the yips before helped him put a stop to them this time—and he believes he can carry that lesson forward.

“At this point, I just see it as something that’s a part of me,” he says. “It’s like someone who has, like, a bad elbow. They’re a good pitcher. They just have a hard time keeping their elbow healthy. You just have to stay on top of things.”

The Bards learned a lesson about the yips. They also learned a lesson about life. Adair thinks often of the phrase, “It’s O.K. not to be O.K.” She thinks it’s incomplete. The second sentence should be, “It’s not O.K. not to ask for help.”

All along, the way to defeat the darkness was to turn on the light.