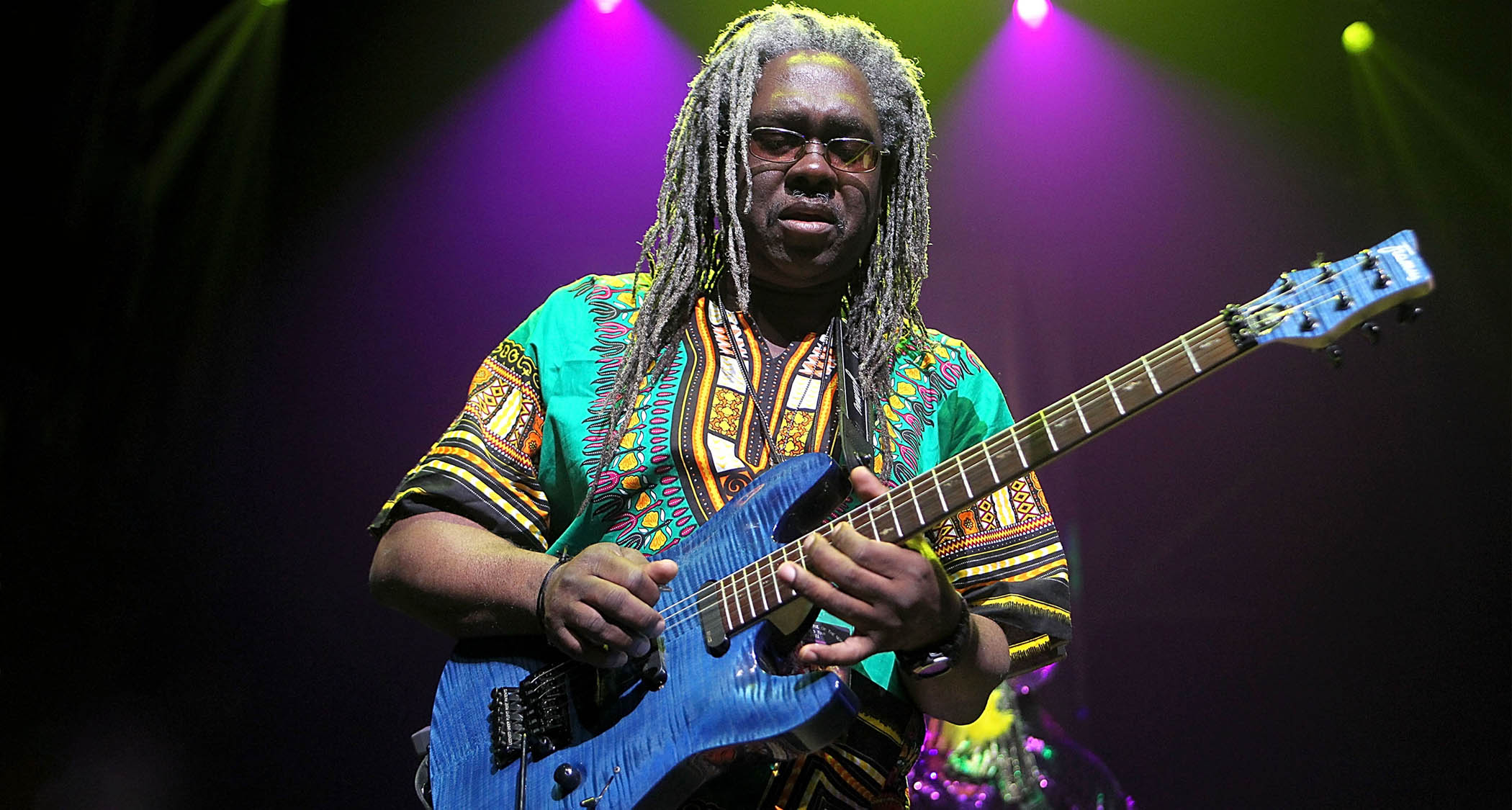

In 1970, DeWayne “Blackbyrd” McKnight was a 16-year-old guitar wunderkind with stars in his eyes. He had the chops; all he needed was someone to notice him, which didn’t take long, as jazz legend Charles Lloyd had taken a shine to McKnight by the time he’d turned 18.

At the time, McKnight was a Strat-loving teen whose smoky tone and nose for what pedals to combine with what amps quickly made him a hot commodity on the early ’70s jazz-fusion scene. But none of it would have happened had Lloyd not given him his start.

“Charles Lloyd is the first of the incredibly talented jazz greats I worked with,” McKnight tells Guitar World. “This man knows everything there is to know about music, and then some. I thank him for his patience and guidance throughout my stint with his band.”

McKnight took that guidance to heart, quickly securing gigs with Herbie Hancock while starring on records by Sonny Rollins, Alphonso Johnson and Bennie Maupin. By 1975, McKnight was still just 21 and swaggering with confidence.

“I had fun playing with those guys the first time we jammed,” he says. “When it was all said and done, Paul Jackson told me, ‘You’re the first person that came in and wasn’t afraid to play with us.’ So, when I go into a situation, I go in, be myself, do what I do, and the rest will take care of itself.”

The proof is in the pudding, as McKnight soon found himself the apple of P-Funk leader George Clinton’s eye. And the timing couldn’t have been better, as McKnight had dived deep into funk rhythms with Hancock, meaning the transition was smooth as butter.

“I was the same person in both bands,” McKnight says. “By the time I joined Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters, we were playing funk, so it wasn’t difficult.

“In fact, it was fun! In the case of P-Funk, if you listen to some of their music, the horns play jazz and the rhythm section plays funk. There are no walls of constriction there. Both bands are taking you on musical excursions that differ from the norm. That’s what I’m talking about!”

Though he was initially drafted in as a member of Clinton’s side project, the Brides of Funkenstein, in 1978, McKnight came aboard the good ship P-Funk in 1979. It was a tough assignment, as McKnight came behind Eddie Hazel and had to occupy space beside Michael Hampton.

The band was on fire and pushed by that killer rhythm section, which brought something out of me that came from the cosmos

“The live shows represented more of me as a guitarist than the records,” McKnight says. “The shows were stellar and energetic. The band was on fire and pushed by that killer rhythm section, which brought something out of me that came from the cosmos.

“To be honest, I took whatever came my way because I was enthralled in music. I knew rock, jazz and funk were three different genres of music, but to me, they were music, and I loved them all. I did the best I could to bring my individuality to each one of these genres. I feel comfortable in any situation because it’s all music.”

Within a year, McKnight was in the studio with P-Funk recording 1979’s Gloryhallastoopid; a few months later, he recorded Uncle Jam Wants You, which rocketed up the charts, though McKnight doesn’t get hung up on it.

“Is there anything I’d change? Probably so,” he says. “But the mark I left is etched in stone and cannot be changed. I’m okay with it. When put on this Earth, we are put here to live, love, learn, procreate and fly.

I was a child who had opportunities thrust at me virtually before I could learn all there was to know about music; I threw myself into situations, and maybe some thought I took on things prematurely

“We’re also put here to struggle, fall, and fail,” he says. “But we get up and keep going until we succeed. We are allowed to do all these things until we learn to fly on to the next stage. I was a child who had opportunities thrust at me virtually before I could learn all there was to know about music; I threw myself into situations, and maybe some thought I took on things prematurely.

“But I took them all on without batting an eye or having any doubts or fear because that’s what was placed before me. The ’70s, for me, were the building blocks for who and what I was to become in the future. Now it’s time to fly on until I become a nebulous mist and move on to whatever is next.”

Entering the ’70s, where were you at musically?

“Entering the ’70s, I was 16, still learning and had little experience, but I was starting to make a name for myself. I got some tips from my friend Shuggie Otis. He told me that one of the keys to playing lead guitar was based on patterns. That helped me a lot. I also watched him like a hawk when he played.

“We listened to a lot of music together, such as jazz, classical, rock, R&B – or soul music, as we called it then. I still had a lot to learn, however. By getting more tips like that from Shuggie, watching every guitar player and learning from records, I began to pick things up a lot quicker.”

What did your primary arsenal of guitars consist of?

“In the early ’70s, I had a four-pick-up Teisco Del Rey guitar with a wiggle stick – you’d call them a vibrato – from K-Mart for $79. Later, my parents thought it was a great opportunity to clean up my room while I was on tour with Charles Lloyd. As you can tell by now, yes, they threw the Teisco away very sneakily. Sadly, the poor guitar was beaten to death.

“I also bought a Fender Telecaster with a natural finish and maple neck at Valley Sound, an instrument repair shop in the San Fernando Valley. I paid $350 for it, which had a humbucker pickup in the neck position.

“I loved that guitar, which was my main guitar for a while. My bandmate Celestial Songhouse wanted to learn guitar, so I traded my Telecaster to him for his Gibson EB-3 bass, which he had taken the frets off of.”

You quickly became known for using Strats. When did those enter the picture?

“On my 18th birthday, my brother bought me my first Fender Stratocaster from Grants School of Music in Midtown Los Angeles for $68. I thought it was a copy, as I didn’t see the Fender logo. One day, I took the neck off the guitar and saw “9-58” inside the neck.

“I showed it to a tech, who told me it was a 1958 Fender Stratocaster. I still have the body. There’s a story about the pickups that I won’t get into, but let’s just say you’d want to kick the guy’s ass like I wanted to. That’s why the rest is a horror story. Again, the cat is out of the bag.”

One of your earliest gigs was in ’72 at the Lighthouse Cafe. Tell me about that.

“During that time, I started hanging out and playing with some of the well-known musicians from the neighborhood. Those players were Woody Theus, or Transcending Sonship of Rhythm Sound and Color, the name he took later, and Sherman McKinney, who played bass with the Craig Hundley Trio and later named himself Celestial Songhouse.

We blended the elements of our styles and called it music rather than jazz, rock, or placing a label on it

“The three of us – Sonship, Songhouse and I – would have gatherings at Sonship’s house. We got on quite well from the very beginning. We blended the elements of our styles and called it music rather than jazz, rock, or placing a label on it. Sonship recorded the gatherings, and we’d listen to them on his Teac four-track tape recorder after the sessions.

“At one point, Sonship and Songhouse decided to present the tapes we made to Charles Lloyd, one of the jazz giants of the time, whom they both were playing with. Mr. Lloyd heard the tapes, liked what he heard and called me down to sit in on a song called Sombrero Sam at the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach, California. Mr. Lloyd liked what he heard and asked me to join the Charles Lloyd Quartet band shortly after.”

From there, you hooked up with Charles Lloyd for Morning Sunrise and Geeta.

“After we went on the road, Mr. Lloyd took us into the studio to record some music for A&M Records. We recorded Geeta at A&M Studios in Hollywood. I remember walking through the halls, looking through studio windows, and seeing Burt Bacharach conducting an orchestra and Billy Preston in another room. It was mad cool!

“Mr. Lloyd allowed us to express our voices pretty much how we wanted. I like that album. I believe Morning Sunrise was also recorded at A&M Studios in 1973. We recorded three songs. One of them was Satie Variations, inspired by Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1. That is one of my favorite cuts from that album, though I love the entire album.”

What was it like working on Sonny Rollins’ Nucleus in ’75?

“It was both exhilarating and terrifying. Bennie Maupin called and told me he was about to do an album with Sonny Rollins, who was also one of the greatest reed men known to me, and he was going to submit my name as a guitarist.

“When I got the go-ahead to do the session, I was very appreciative. Still young and not yet experienced enough, however, I decided to take on the task as it was a great opportunity for me.”

Being as young as you were, did you have any nerves?

“The session went very fast. We recorded the songs I played in two days or quicker – for some songs, we were given directions, and for some, we were not. Mr. Rollins also gave us the freedom to do whatever we wanted. The butterflies in my stomach were flying fiercely, but I persevered.

“I was in awe of working with Mr. Rollins. My father had a broad collection of records, including Sonny Rollins’ records or albums he played on. When I was a kid, I used to go through his record collection, take out albums to look at the pictures – Pop didn’t like us messing with his record player – and read the graphics.

“Sonny Rollins’ mohawk hairstyle caught my eye, so I used to hand his albums to Pop and asked him to play them. Needless to say, they were great. So I knew about Sonny Rollins and his legacy when I got the phone call, and it was an absolute honor and privilege to have worked with such a jazz great.”

That same year, you worked on Herbie Hancock’s Man-Child and Flood.

“For Man-Child, Herbie was due to release a new album on Columbia Records, and he used the Headhunters. The two songs I played on are Sun Touch and Heartbeat. I enjoyed those sessions and working with Wah Wah Watson, who helped me with playing in the pocket.

“As far as Flood, after the Headhunters’ album Survival of the Fittest, Herbie embarked on a tour of Japan with his Headhunters group, and I joined. While on tour, we did two days of recording for a live album in Tokyo. It was my first time in Japan. I liked Japan very much.

“I was very happy. Maybe it showed in my playing because I still receive compliments on my playing from that album. I was stoked to be included on a live album with Herbie Hancock.”

How did you approach the tracks?

“I approached the tracks the same way as I did with all the sessions I got. I practiced religiously to be ready for whatever came my way during the sessions. Once the tune was played a couple of times, I had it down. Herbie let us do our thang. I love the whole Man-Child album, especially Hang Up Your Hang Ups and Sun Touch.”

What gear did you have in the studio with you?

“I remember using a Les Paul with mini-humbuckers, an MXR Dyna Comp, which I permanently borrowed from Paul – yes, I still have it – and a Fender Twin Reverb. As far as Flood goes, I have heard pieces or sections here and there, but I haven’t listened to the whole album yet. I used the same Les Paul straight through a Fender Twin Reverb amp. If I had any pedal setup, I don’t remember.”

You didn’t meet Herbie until Survival of the Fittest, right? What did he think of your guitar playing?

“Correct. I met him at Wally Heider Studios in San Francisco during the recording session of the Headhunters’ album Survival of the Fittest. Meeting one of my favorite musicians and being involved with his band was nice.

“Herbie is one of the nicest guys I’ve met, so not only did I love his music, but I also loved him as a person. He didn’t comment on my playing then, so I don’t know what he thought.”

You aren’t often asked about Alphonso Johnson’s Moonshadows.

“The Moonshadows session was a surprise. I knew about Alphonso Johnson but never thought I’d get a chance to work with him. The track I played on was Up from the Cellar, which was a very well-put-together track. I used my Fender Stratocaster, MXR Distortion +, MXR Dyna Comp, an ADA Flanger and a Mu-Tron III, which was probably in the first batch made, and I still have it.”

And how about Bennie Maupin’s Slow Traffic to the Right?

“I used to go to Bennie’s house and work on some of his songs in their infancy. I was thrilled he would ask me to play on one of his albums. Going to his house and working on his music with him prepared me for the upcoming album.

“When I’m in a studio recording with anyone, I listen to the song and blend in with the musicians to make the song gel. That is the approach I use with everyone, and it was the same with Bennie. I don’t remember exactly what gear I used for this session – probably my Les Paul and Distortion +.”

What did playing in the Headhunters and with other jazz musicians teach you that you carried into the Brides of Funkenstein and P-Funk?

“The first jam with the Headhunters took place in Oakland at Paul Jackson’s place. We weren’t [strictly] playing jazz. During that time, Herbie had released the album Headhunters, which had jazz elements in it, but to me, it wasn’t exactly a jazz album. We funked! And hard!”

Mike and Eddie were OG funk, and I had a different flavor, so you had three totally different flavors to enjoy. Mine is the most avant-garde, but that’s where I was coming from

So, how did you join the Brides of Funkenstein, which led to your becoming a member of P-Funk?

“I was walking home one day and heard a guitar playing. Back then, I would knock on the door whenever I heard a guitar playing. The guy playing the guitar came to the door and invited me in. We became friends from that day on.

“The guy’s name was Ronald Brembry, who went by the nickname of Brem. He also joined the P-Funk camp at the same time I did and worked on the staff. After that, I would stop by his house and jam together often.”

“On one occasion, Brem took me to his friend’s house for a jam. His name was Archie Ivy, who also played bass, and we jammed for a good while. I later found out that he was the president of Parliament Funkadelic, which was my favorite group. He told me that in about a year, Mr. Clinton would be forming a new band, and he would set up an audition for me. I never forgot what he told me.

“A year and some change later, I did get this call from someone I didn’t know, and the conversation went something like this, ‘What are you still doing at home? You’re supposed to be on a flight going to Detroit to audition with the Brides. You missed your flight. How soon can you get to the airport?’ Needless to say, there was no flight booked for me. No wonder I was still at home. That was my introduction to P-Funk.”

“That was September 1978. Enter the organized chaos. I caught the red-eye to Michigan and went to the Balmar Hotel in Detroit, a very funky joint, but hey, we’re talking about P-Funk, right? When I got to the hotel, I was taken around to meet some band members I’d be working with.

“The next day, I auditioned for the Brides of Funkenstein and was hired. In late September ’78, the Brides set off to open for the P-Funk Anti-Tour. After the Brides dissolved, I became a member of P-Funk in late ’79.”

Was it tough shifting from jazz-fusion to straight-up funk?

“Not actually tough because my idea was to fuse jazz and funk together anyway. So I just went in, applied myself and contributed to the situation the best I could. During that time, I was paying more attention to music composition, the groove and the likes thereof. To me, it was all music, and I found a better way to express myself in both genres.”

Did your gear change much?

“Yes, my gear did change. With Herbie, I used a Les Paul, Dyna Comp, Distortion +, A/DA Flanger and a Maestro Guitar Synthesizer they rented – which I used on Hang Up Your Hang Ups – into a Twin Reverb. With P-Funk, I used my Fender Strat, a Cry Baby wah and an MXR Distortion +; later, the Distortion + was replaced by a pedal called Ross, which was permanently borrowed from Brem.

“I still have them all. We used Music Man heads that somebody told me were owned by and modified for Aerosmith [and] then acquired by P-Funk. Those amps were hot!”

Gear aside, what were your first impressions of George Clinton?

“I didn’t meet George until late into the Anti-Tour, my first tour with the Brides/P-Funk in September ’78. I would see him on stage during the performances, but I never ran into him off the set or at the hotels, as he stayed at different hotels than the band.

“The band usually wore outrageous costumes, but for this tour, they decided to wear army fatigues. That’s why they called it the Anti-Tour. I finally got a glimpse of Mr. Clinton backstage at one of the gigs. I was walking down the staircase at a club we played, and he was walking up.

“When we passed each other, I heard him speak in that undeniable voice. I turned around, looked at him, and thought, ‘Wow, that’s the cat that put this whole thing together, the Maggot Overlord himself.’ No words were exchanged. He was wearing a fatigue outfit that was funked-up to the max. I was stoked, to say the least!”

Did you find it challenging coming in after Eddie Hazel, and what was the key to locking in with Michael Hampton?

“I started playing with P-Funk in 1979. After the Brides shows, I watched the shows every night. They were one of the baddest bands I’d seen at that time. So, by that time, I got to know Michael and Eddie pretty well, two of the coolest and most talented dudes you ever want to meet and listen to on a nightly basis.

“Mike and Eddie were OG funk, and I had a different flavor, so you had three totally different flavors to enjoy. Mine is the most avant-garde, but that’s where I was coming from and bringing to the band, which was what I had in mind and one of my goals, as it were.”

Do you remember your first studio session with P-Funk?

“My first session with George was at the Disc Studio in Southfield, Michigan. Before the session, I gave him a tape with some songs on it. He liked them and asked me to cut them in the studio.

“If I’m not mistaken, my first song was The Freeze (Sizzaleenmean). That song was on Gloryhallastoopid. I think the session went very well, and George put the song on an album, so I guess he thought so as well. After that, I started working my way into becoming one of the regulars for recording sessions.”

Is there a P-Funk moment that best represents the player you were to that point?

“I’m proud of everything I did with P-Funk. One is The Freeze (Sizzaleenmean) on Gloryhallastoopid, which I wrote and played all the instruments on, except sax. In the same year, 1979, I co-wrote with George Clinton, arranged and played guitar on Freak of the Week for Uncle Jam Wants You. These albums are certified gold, and I’m proud of both.”

Is there a guitar, amp and pedal that most defined your work, sound and style in the ’70s?

“The guitars were mostly Gibson SGs and Les Pauls or Fender Strats and Telecasters. But my favorite sounds came from a Fender Stratocaster. My favorite guitar is, without a doubt, a Fender Stratocaster.

My favorite sounds came from a Fender Stratocaster. My favorite guitar is, without a doubt, a Fender Stratocaster

“The first real amplifier I bought was a Marshall 100-watt head, which I won’t tell you about as it is a disaster story. I also owned an Acoustic 150 amplifier, which I used for a good while. The next amp I used was an AMS 212 combo amp; I’m still trying to find one of those! My father purchased it for me, and I cherished it.

“As far as pedals go, I used a chrome-plated Vox wah, a Cry Baby wah, a MXR Distortion +, a Univibe and a Roland sustainer/compressor because they gave me the sounds I was looking for and could afford at that time. My pedals varied, so these were my favorites and defined the sounds I was experimenting with in the ’70s.”