When Omer Arbel started his design company Bocci almost 20 years ago, his experimental approach to manipulating glass and other materials into novel forms, and then turning these into commercial products like lighting, catapulted the Canadian architect and designer to fast success. Ever since, Arbel and his team have never stopped experimenting, constantly finding new processes and materials, and applications for them at scales from table lamps to private residences – each a numbered entity in a growing archive (hence 75.9 house in Vancouver, which we explored in 2023). Ahead of Bocci’s anniversary milestone, Wallpaper* spoke to Arbel about how his practice has – or hasn’t – changed during this time; being a ‘matchmaker’ between the company’s and external opportunities; and a surprising use for the doomed cedar trees in the Pacific Northwest.

Omer Arbel on his everchanging practice

Wallpaper*: Bocci is about to celebrate its 20th anniversary. I’m curious to know how your approach to your work and your practice has changed and shifted over these two decades?

Omer Arbel: The core principles, let's call them our aesthetic mission, haven't changed. They've become more sophisticated, possibly, and better supported and maybe more uncompromising. But they haven't changed. What has changed is my own comfort in the situation. In the beginning, there was tons of pressure, because we had very little breathing room. We were a young company, and things had to sell for us to keep our staff and to keep thriving. Pressure to release pieces at certain dates, maybe before I was comfortable with them, or before they were ready. Pressure to make things that we thought would have a chance of selling. And that pressure has receded a lot.

Now, we release things when we feel they're ready, not when the market wants them. We introduce projects that we love; not because we think other people will love them. Sometimes they don't sell, and that's fine. So I would say, I think the main change is not the mission or the process, but rather our own feeling of comfort and confidence.

W*: You’ve previously discussed comfort as a principle that dictates the experimental portion of the practice, and that being uncomfortable is something that pushes and drives innovation. Can you expand on that?

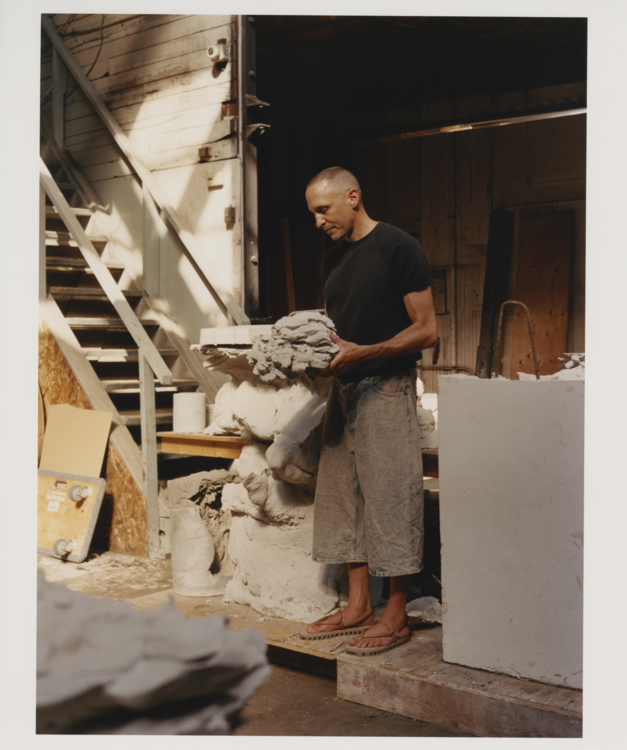

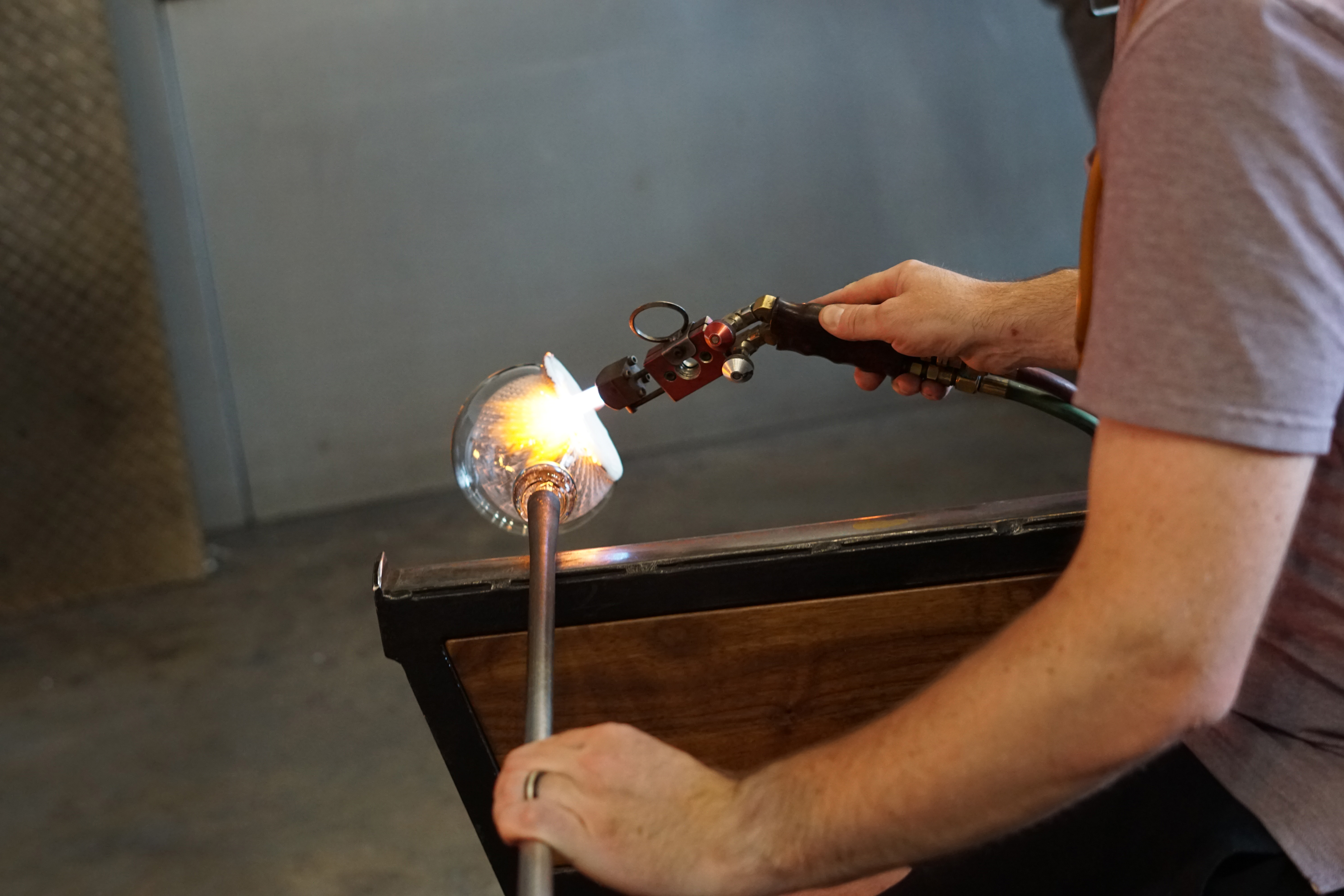

OA: The reason we get all these fascinating forms is because I'm making the materials uncomfortable. I introduce all of these extreme stresses on process, around a material’s intrinsic properties. Those particular stresses can only be resolved in a way that makes what we consider to be exciting forms, which is so different from anything anyone else is doing.

‘I do create discomfort and use it as a creative tool and an aesthetic generator’

Omer Arbel

There's all kinds of constructed discomfort that I create in the studio, because I find the resolution of those to be almost like a grain of sand inside an oyster that ends up becoming a pearl. So I do create these intense situations on purpose that seemingly have no resolution, but they actually do, and the resolution is some very exciting form. On a personal level I feel totally comfortable now, but I do create discomfort and use it as a creative tool and an aesthetic generator.

W*: And how does that thread between lighting at one end of your practice and architecture at the other?

OA: In our studio, there's very little difference in any of these investigations. But the way the world perceives them is a whole other story, because people have expectations of certain projects. Is it a work of architecture? Is it a piece of research? Is it an artwork, or a product? And there's three different procurement methods and economics for each of those outputs. But at its core, we're just doing the same thing: playing with materials and processes.

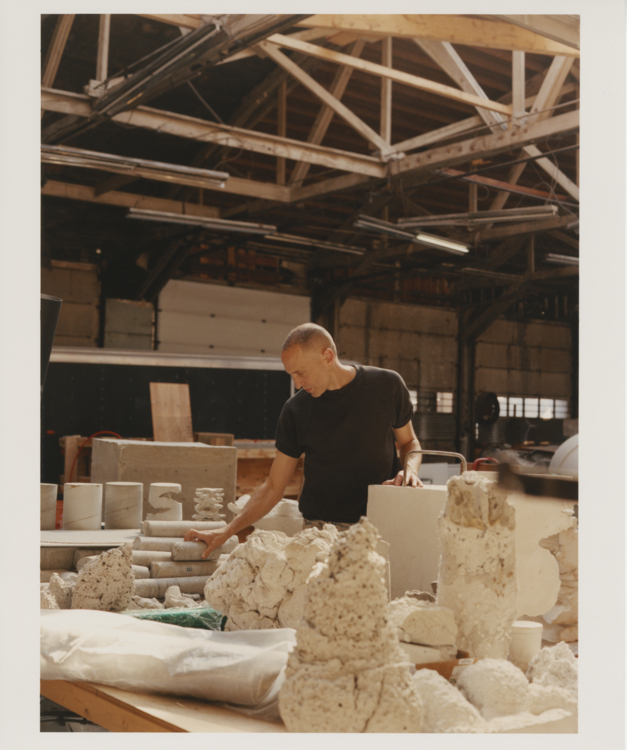

The way our studio functions is that my job – with a team of around eight creative collaborators and makers – is just to make stuff all year long, exploring materials based on our intuition, without any schedule, budget or scale. We're not responding to briefs. And then a few times a year, my business partner and I sit down with all the things that we've found over the course of several months, and just evaluate what each of those discoveries wants to be. Does it want to be a product? That question usually relates to how much it costs to produce, and whether we can imagine a way of delivering something very complicated, usually, at a price that people could actually afford.

If we want to zap glass with lightning bolts, that's obviously not going to be a product, it requires a huge investment in money, time and resources. So we think of it as research. Or, does it have practical application on a construction site? There's so many different ways that we are working with fluid, dynamic materials, like concrete, that are applicable directly to construction methodology. And because we are so excited and we love building things so much, many of those areas of research end up being investigations for architecture.

We have an archive of ideas already, and then whenever opportunities come, we match the idea that we already are in love with to the external opportunity that comes along. We're just matchmakers.

W*: Can you provide a couple of examples of how you've applied some of these material innovations or research methods to commercial architecture projects?

OA: Project 94 [a group of private houses at Governor’s Point in Washington state] is a good example. To preface, because of climate change, our region is getting warmer, and many of the old-growth cedar trees are perishing. The very rich, intense forest here in British Columbia is part of everyone's lives in quite an emotional way, but also it's one of the largest industries of this region. The cedar trees dying is a massive tragedy, but the economic ramifications are interesting, because it means that there's all this very high-quality cedar all of a sudden available as lumber, and there is a thirsty market for it. People are making a fortune just cutting down their cedars and milling them for lumber – almost like a gold rush.

The lumber is only viable as a product if the grain pattern of the wood is consistent. At the bottom of these prized cedar trees, what's usually called the burl, has [an] inconsistent pattern because it's where the grain of the trunk meets the root ball. So you have these very swirly patterns of the grain of the wood. And I learned that in this Gold Rush context, those burls are being mulched. So at this point in place and time, you can get cedar burls for almost no money. And I developed a tumbling method for these cedar burls, where we tumble the bits of wood in an industrial-scale tumbler – similar to my daughter’s rock tumbler, but huge. This results in boulders of cedar, in various shapes and sizes, which are rounded and softened in this really attractive way.

‘The reason we get all these fascinating forms is because I'm making the materials uncomfortable’

Omer Arbel

For project 94, we’re using these as a void material to form the concrete around, using huge bundles of the cedar orbs to create a relief texture on the inside of the building. After the casting, the same orbs are used as cladding for the building, creating what we’re calling a ‘cloud’ of them from half a metre to two metres outward of the building envelope. So the houses will be these cedar clouds with openings in them for windows and doors. Over time, they’ll silver, and lichens, mosses and maybe even creatures like birds and lizards will start inhabiting the cedar cloud, so it'll become a landscape veil or scarf that the houses are wrapped in. That's an example of how our process-based approach interacts with architecture. Much of the building remains conventional construction, but this one key part of it, the building envelope, is a direct result of a process that we've invented.

W*: Aside from your base in Vancouver, you also have spaces in Berlin and in Milan. What is their purpose, and how do they operate?

OA: They're very different cities and they're very different spaces. In Berlin, it's a gigantic industrial space for exploration, research and collaboration. It's full of potential and has very few restrictions. We see it as a way of inviting a constellation of other artists into our universe, collaborating with others, but also exploring our own works at scale in a laboratory environment.

Meanwhile, Milan is a city and a space which is much more intertwined with its history. Milan has such a strong tradition of design and is the commercial centre of our industry, and the space we have there is a very beautiful apartment. Our intent there is quite opposite to Berlin. In Milan, we show our work in the context of the greater community around us, all the other brands, and in the context of a domestic apartment with much more formality.

W*: Bocci unveiled a significant rebrand last year. How has the new visual identity served the company so far, and how do you hope it will direct its future?

OA: Studio Frith did an amazing job for us. I felt uncomfortable with our brand for a long time because I felt that it was presenting the work in a way that any marketplace would, without any acknowledgement of the novel processes that got the pieces to where they are. I'm not objecting to the commerce, but what I do like about the way Studio Frith handled our brand is that they told the story of the works and of the culture of our studio in a way that I feel very comfortable with.

Now our brand is much more honest to what actually happens in our studio. For a long time, we were wearing clothes that we were uncomfortable in, and now we're wearing clothes that we feel much more comfortable in and suit our personality. I don't think anybody thought of it as a thing for our business. And in terms of how we see that propelling into the future, I think we've only just started. The stories of the works are so rich and so delightful, and there's still a long way to go.