SAINT-DENIS, France — For years, the greatest hurdler who ever lived watched a promising athlete from Virginia power his way toward greatness. This kid didn’t run so much as he motored.

This kid hurdled like a car from the 1960s—a Dodge Viper, or Ford Torino—only with modern technology’s most souped-up engine built into his 6'2", 190-pound frame. This kid ran like the NFL player he could have been, had he not waved away college football scholarship offers from programs like Georgia. This kid, Grant Holloway, became a hurdler instead.

In some ways, Holloway reminded Edwin Moses of Jim Brown. Same height. Forty pounds lighter. Smooth gait, at least to observers, but certainly not to anyone attempting to tackle him. Both presented power and speed, peril within grace. Imagine if Holloway put on the weight he’d need to play professional football. He’d look a lot like … A.J. Brown – and with even more speed.

When Holloway grew from that kid into a large, muscled man among other large, muscled men, Moses knew he had to meet him. They didn’t specialize in the same event—Moses won 122-straight 400-meter hurdle races; Holloway triumphs in the shorter hurdles races (60 meters, 110 meters), often finishing races in less time than it takes to fold a T-shirt.

And yet, from 2021 through mid-‘24, all anyone seemed to want to ask Holloway about was that other Olympic final, three years ago, where he “lost” gold by 0.05 seconds. He hadn’t dropped a major race since. Not once in three years. The last person to dominate a hurdle discipline like that? Moses.

He wanted to see Holloway’s size, because Moses could already ascertain the depth of technical skill. They’re the same height. Both had to figure out ways to, Moses says, “regulate” their strides. In the 110-meter version, the hurdle is taller, but principles—of physics, aerodynamics and responses to both—are applied in similar ways.

Meet, they did—on May 31, at the Edwin Moses Legends Meet, roughly two months before Holloway would hunt for that elusive gold. Moses takes it from there. “And, my God,” Moses says in Paris. “I didn’t know how big he was, his size, anything like that.”

He found Holloway larger, more muscular and more imposing than expected—and he expected to find Holloway large, muscular and imposing. He wasn’t built like an NFL wideout. He was built like an NFL practice facility. But even more than that, Moses noticed something else. Holloway was also built to run one specific race.

“He’s custom-made to run those hurdles,” Moses says. He laughs. “If Grant hits a hurdle, that hurdle is … going down.” He laughs again, harder this time. “I’d hate to get in the way of his forearm.”

Upon arrival in France, Holloway described himself as a “sore loser.” He even remembered the last time that anyone had beaten him in a competition – last September. Moses understood that mindset. Even in an Olympics, he’d rather finish seventh than second. “You get your ass kicked. You move on.”

Holloway grew up in Chesapeake, Va. He wasn’t exactly a born hurdler. Or, if he was, that wasn’t clear yet. Athleticism reigned. He played several sports and often with Stan, a retired officer in the U.S. Navy, as coach. Around age 15, Grant’s body started to develop. Tall, fast and strong, he would gain weight for football and lose it for track.

His father didn’t mind the variety. But in Grant, around that age, he saw what Moses would see later—a body that all but screamed elite hurdler.

Eventually, Grant whittled his athletic ambitions to track and football. In track, he sprinted, hurdled, high jumped and long jumped. He trained at the Track 757 club, where Stan was an assistant coach. In football, Grant played receiver and defensive back for Grassfield High. Dozens of offers pour into the school’s athletics office—Clemson, Tennessee, Michigan and the Bulldogs, of course. Many wanted him to compete in both.

Holloway did not. He decided he liked competing by himself, the most significant factor in a close and difficult decision. He chose Florida for college, but not to score touchdowns in The Swamp. He wanted to run for Mike Holloway (no relation). This season marked his 22nd as the university’s men’s track coach, where SEC championships are the minimum expectation and national titles the real prize.

Together, they won three national championships at UF; Holloway eight individual crowns. “Florida took him to a whole ‘nother level,” Stan says. “Coach Holloway had started something Grant just needed to finish.”

It didn’t take Grant long to level up. He turned pro and kept winning. They called him the Wonder Boy, and the Wonder Boy left UF in 2019. In the five years since, he won three world championships, one Diamond League final and that silver medal that felt more like a loss. This year alone, he erased a 30-year-old indoor world record in the 60-meter hurdles, finishing in 7.29 seconds and clocked a 12.81-second 110 in the U.S. Olympic trials, good for the second-fastest time, ever, in that discipline. He held the fourth-fastest time (12.86) too. Of the 13 times in track history that a hurdler broke 13 seconds at that distance, 10 of those are his marks.

Told of the praise from Moses, Holloway’s face twisted in something like surprise. He praised the legend right back, then delivered an answer that was neither braggadocious nor subtle. “Um, do I feel I’m dominant?” he said. “Uh, yes.”

Proof: in Paris, Holloway breezed through his heats. In his semifinal, he ran a 12.98 seconds. That would have won gold, too. He won the final in 12.99. Redemption? At last? No way, Holloway told reporters.

When an athlete like Holloway wins a gold medal like he won his in Paris, the spotlight descends with a glorious fury. Cameras trained on Holloway late Thursday, as did millions of eyeballs and thousands of cell phones cameras at Stade de France. Beats thumped. Then came the hugs, pounds and hi-fives; the deluge of praise; and the endless interviews.

Two days later, he still looked a little tired from the less-immediate aftermath. Asked about that longer aftermath and any detail he might provide, Holloway chose a more immediate moment instead. He had heard about the bell that winners (and only winners) rang inside the stadium. That it will later be placed in Notre Dame Cathedral. That sentiment stuck with him.

“I’m part of history here in Paris,” he said.

He also said the enormity of his triumph had yet to hit him. He plans to sit outside, once home in Florida, sip some tea or maybe allow for a glass of wine, and reflect. Only then will he see what bubbles up.

Chances are, he’ll consider his now-famous arc.

On Thursday night, at Stade de France, Stan and Latasha Holloway stood near the section where parents of U.S. athletes sit. Their son would compete in 30 minutes, in another Olympic final, the one that wasn’t necessary to confirm his dominance—and yet, also the one that would eliminate any final slivers of doubt remaining.

Everyone nearby wanted pictures. They opened with, “Your son is awesome,” and, “You guys are awesome.” What the Holloways wanted was for Grant to be awesome, on that purple track, and not for them but for him, to end this particular narrative. It centered on the silver medal he won at the last Games. On that day, he didn’t feel like he “won” anything.

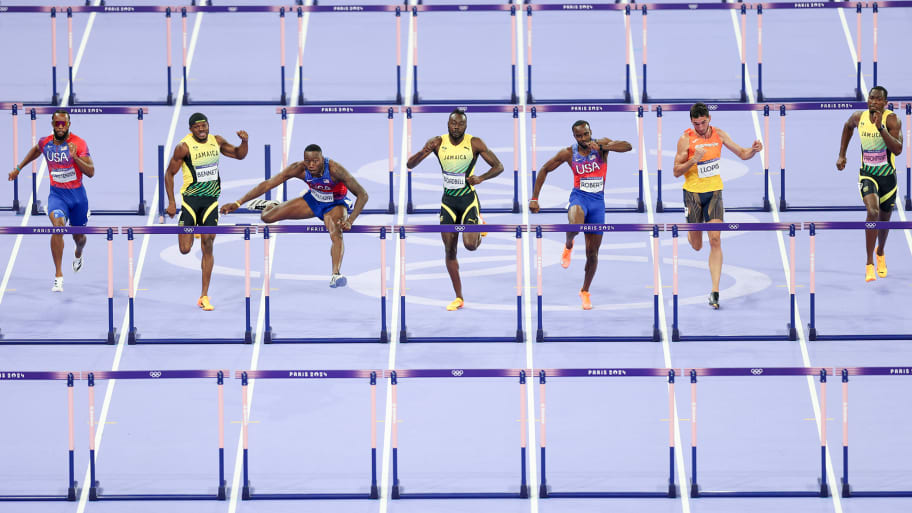

Holloway’s race was the final event on the third-to-last day of the Paris Games. Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone had just set a world record in the 400-meter hurdles. Now, it was Holloway’s turn.

As the gun sounded, his start wasn’t ideal. But his steps were, and that’s what mattered. Holloway sailed over hurdles, gaining speed, creating space between himself and the rest of the field. Every movement was equal parts Muscle Beach powerful and Prius efficient. Hurdle. Three steps. Hurdle. Three steps. All the way through the finish line.

Yes. To understand why, context matters. As do two literal steps.

That Tokyo performance wasn’t a disappointment. Not to anyone but Holloway. Anyone near him in the mixed zone, where interviews are conducted in airport security-style lines with steel barricades, will never forget one particular exchange.

Holloway wasn’t disappointed. No, he was far more heated than that. He was angry, as if someone had rushed onto the track and added matchbox cars, sand burrs and broken glass in only his lane. Adam Kilgore of The Washington Post gently pointed out the obvious. Holloway was 23 years old then. He had just won a silver medal at the Olympics. The gap between him and gold was infinitely smaller than it took Kilgore to ask his question. He hadn’t yet received his medal. He looked like he didn’t want it.

The silver medalist scanned the reporters huddled in around him, separated by a barricade. He asked them how they might feel if they were, say, the second-best writer in the world. Heads scanned. Shoulders raised. Consensus: pretty freaking good.

That’s not how Holloway is wired. Not how he competes or why.

Moses saw something in the way Holloway races. Typically, he wins or loses based on two steps. The very first two he makes, in fact. Perhaps that sounds like an exaggeration, but Stan Holloway, Grant’s father, confirmed what Moses saw on Thursday night at Stade de France.

“His first two steps are the most important,” Moses says. “Before he’s even taking off, that’s where the rubber meets the road for him.”

Speed isn’t exactly the issue there. Timing and rhythm shape success or failure. Holloway couldn’t gingerly tiptoe into a race. And he couldn’t start so slow as to fade from contention. But those steps assume paramount importance because of all the other steps that follow them. Holloway is so big, in an event where the distance is so short, that he must begin 110-hurdle races with precisely the right timing.

What only someone like Moses or Stan Holloway would know is that elite hurdlers typically don’t “count” their first step of the race. They make it—and then they begin counting. They leap the first barrier and ideally take exactly the same amount of steps before they leap again. In Holloway’s case, in that particular race, three steps, taken in precisely the right spots on the track, after every hurdle—that’s the ideal.

The first two matter, because they determine how he’ll clear every hurdle down the track, all the way through the last one. If he gets out too fast, he’s more likely to clip a hurdle through momentum alone. If he gets out too slowly, he’s more likely to try and pick up his pace, which is most often done by extending one’s stride. Moses says this is natural—as in, it’s human nature to try and catch up. And yet, it’s not the right correction. “The only place you can regulate,” Moses says, “is right there.” At the beginning.

Told all this, Stan smiles and furiously nods his head. In Tokyo, his son was the reigning world champion and the favorite. But that start did not separate Holloway from the pack, as typically happens when he races. His rhythm was off, right away. Still, Holloway pulled ahead by the 60-meter mark. Just don’t mistake leading for rhythm. He clipped the seventh hurdle, broke form and leapt over the final three barriers from a jump point that wasn’t obvious to the casual eye but was, to those who understand the hurdles, far too close. When a hurdler does that, they lose momentum. They’re jumping upward, even just a little. And when they do that, they’re not jumping forward, which is up but not the same.

“[Those] steps dictate if I’m going to win that race or not,” Holloway says. He copped to “God-given ability” that allows him, sometimes, to recover where others would not.

That he still nabbed a silver medal and almost won anyway, spoke not to failure, but to Holloway’s immense gifts. Two steps. That’s all that cost him gold.

In Paris, Holloway understood that how fast he ran mattered—of course, it did—but only running the right way and fast would net him what he wanted most. He was fast in Tokyo. He also staggered through his step and even turned his head near the finish line. In a race decided by 0.05 seconds, that’s enough to lose.

Late Thursday he said he actually cramped in Paris, near the end of his face, maybe at hurdle No. 9. When pressed as to which leg cramped, he responded, Both. The difference was he already led by a large enough margin to withstand it.

What gave him that lead? Those first two steps, of course.

“I won an Olympic gold medal,” Holloway says. “So I [would] say they were pretty damn good.”

Still, that might not have been obvious. He didn’t shoot from the starting blocks like a low-trajectory human rocket. In fact, his teammate, silver medal winner Daniel Roberts, left the gate ahead. Holloway didn’t need to win the first 10 meters. He needed to regulate his stride and not fall too far behind. He did both. Then, the world record holder in the 60-meter hurdles turned on that afterburner speed.

He didn’t break the world record. But few in track and field think he won’t ever break it.

By late Thursday, Holloway had completed track’s version of a grand slam. He continued to say it wasn’t redemptive, Olympic gold, but he also said he felt relief at having ended all the questions that persisted, nagging at him, once and for all. Which sure sounded a lot like redemption, no?

Regardless, Holloway has entered rare territory. He’s on a similar trajectory to Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone. He’s not as far along as she is in terms of changing what’s possible for short-distance hurdlers. But what tethers both is who they’re racing—not humans but history and the clock.

Now, Holloway says his plan is to win at least one major championship medal every year. This will give new meaning to the cliched question, “What do you want? A medal?” In his case, the answer is both realistic and, well, yes.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Olympic Champion Grant Holloway Is Wired Differently.