They always say, if there is an accident with nuclear, it’s gonna be the end of the world. That’s bulls***,” says Oliver Stone. The great, daunting topic of nuclear energy sits at the centre of Stone’s latest film, the documentary Nuclear Now. The multi-Oscar-winning director built his reputation on snap and excess: the violent crime odyssey Scarface (as screenwriter); the visceral Vietnam war drama Platoon; the insatiable Eighties satire Wall Street; the three-hour-long conspiracy-theory-laden thriller JFK. His latest project, though, is one of frill-less conviction.

I’m meeting with Stone, and Nuclear Now’s producer Fernando Sulichin, in the bar of a central London hotel. They are in the country for a pair of private screenings, and they begin by reflecting on the previous night’s event. Unusually, none of the talk really concerns how the film was enjoyed as a work of cinema, but rather, how receptive the audience were to the film’s argument. This makes sense: Nuclear Now is filmmaking as manifesto. The documentary has an ardent message, and it doesn’t waste much time entertaining alternative points of view. Nuclear energy, both men aver, is the only practical road to a green future, and the survival of our species.

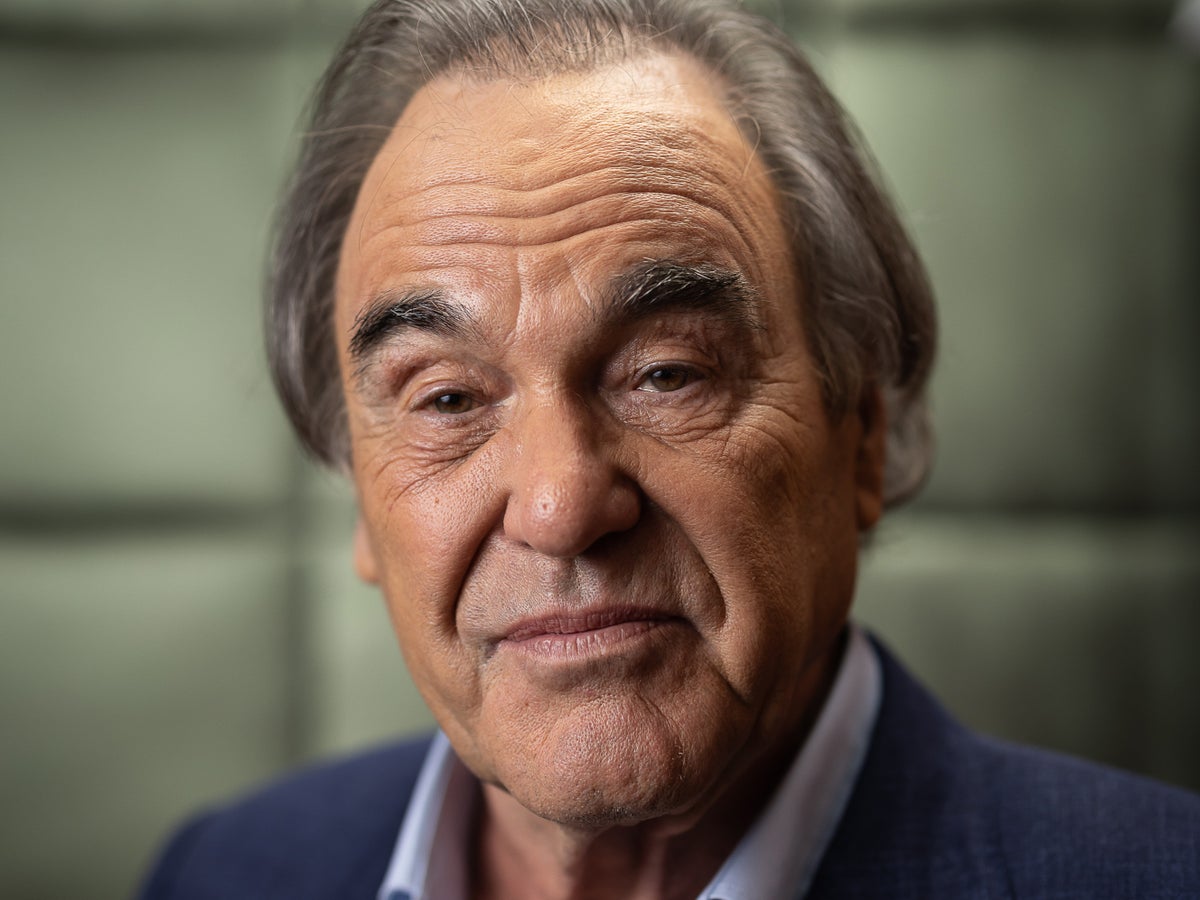

“I was a young man in the Seventies and Eighties,” Stone explains. “I believed what Jane Fonda was saying, and Ralph Nader, and Bruce Springsteen. They were heroes – so I went along with it. But as the situation deepened and the years went by... It’s been over 20 years since the year 2000, and still, 84 per cent of the world’s energy comes from fossil fuels.” Stone is no longer a young man, of course – he’s 76, to be exact – and has an air of world-weariness about him. When he speaks, though, it is with a bearish intensity. “Obviously I’m not gonna be here in 2050,” he says. “But my children, and hopefully grandchildren, will be.”

Nuclear advocates emphasise the technology’s relative cheapness, scalability and reliability – unlike wind or solar, its output is not beholden to weather patterns or day-and-night cycles. “We’re not saying [these clean energies] are bad,” Sulichin assures me. “But in order to power the electric grid of England, with the wind you have here, you need to surround practically the whole island of Great Britain with turbines.”

This isn’t strictly true. As an island in the North Atlantic, Britain has the best natural resources for wind, wave and tidal power generation in Europe. It already supplies around a quarter of its energy needs from wind, and is committed to raising capacity to 50 gigawatts by 2030 (peak demand at present is just over 60GW). But the UK is by no means typical.

Smiling politely next to Stone, Sulichin cuts a markedly less intimidating figure than the Vietnam war veteran. But he is no less invested in the nuclear argument. “Hopefully we’re making a small dent in people’s opinions,” he says. “Climate change [is everywhere]. It’s very hot now, there’s floods in Italy, hurricanes... it’s here and it’s there. And people keep dancing on the Titanic.”

This isn’t Sulichin’s first collaboration with Stone – the Argentine has previously joined him for projects about Edward Snowden, Hugo Chavez, Fidel Castro, and – most infamously – Vladimir Putin (more on that in a bit). “I’m kind of the person who has to support Oliver’s vision and make it happen,” he says.

Stone was turned on to the nuclear issue after reading A Bright Future by Joshua Goldstein and Steffan Qvist, the non-fiction book that would eventually be adapted into Nuclear Now. His first thought was, could they make it as a drama? He went as far as commissioning a treatment. “It was my idea to make it about a female scientist, because they’re popular these days – a female scientist with a male flunky, or something.” Stone grins a little maniacally. “And in order to save nuclear energy, she has to basically perform the same tricks as Tom Cruise.”

Unsurprisingly, that idea didn’t come to fruition. While nuclear armageddon has proved a febrile plot device in disaster films such as Dr Strangelove or The China Syndrome (both glancingly referenced in Nuclear Now), the sterile, prosaic reality of it is not really the stuff of popcorn entertainment.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7-days

New subscribers only. £6.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7-days

New subscribers only. £6.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

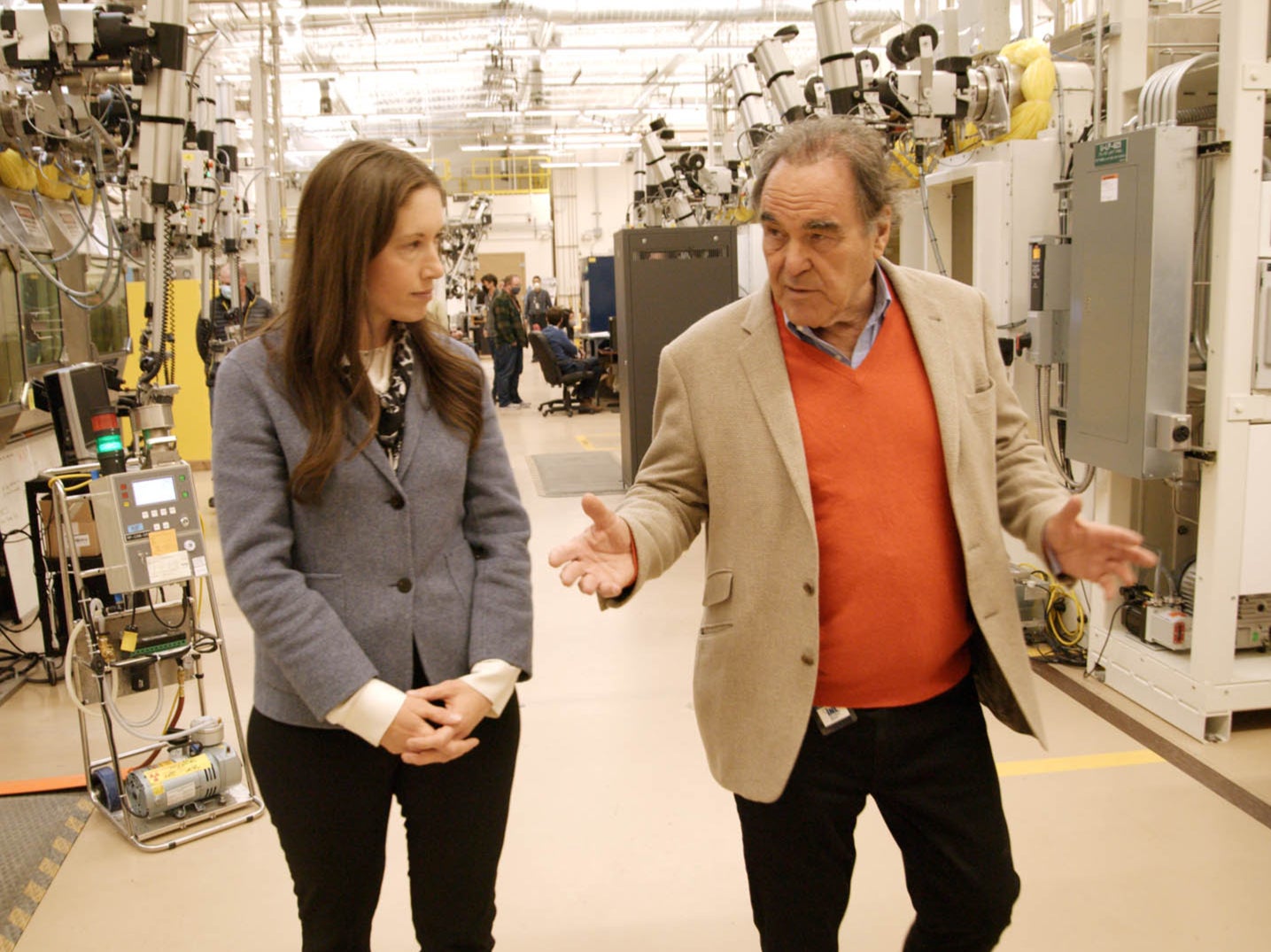

So in the end, the filmmakers opted for what Stone calls an “unconventional” documentary – “because we use a lot of sloppy, ugly footage from the archives. We had to. There’s nothing, no other footage. So we tried to incorporate interviews, and bits of wonderful old footage, but some of it was pretty hard to see.” Nuclear Now also incorporates modest graphical flourishes, a few appearances from Stone himself, and case studies – including a first-hand look at Russia’s nuclear infrastructure.

A while into our interview, Stone grows irritated by a conversation coming from a table some five metres away (“I hate the sound of that guy’s voice!”). So we abscond to a more private room. Here, the sofas are some distance apart; he winces and cranes his neck in an effort to hear my questions. I am, as Jerry Seinfeld would say, something of a “low talker”. I momentarily consider asking Stone about Seinfeld – which memorably lampooned JFK – but no, the vibe in the room is all business, and some part of me fears he would scowl my head off.

People confuse nuclear energy with nuclear weapons – they have nothing to do with each other— Fernando Sulichin

I more or less yell my next question at him: what about the dangers of nuclear meltdown? The worst-case scenarios? Is that just a risk we need to make peace with? “The worst-case scenario already happened,” he replies. “We’ve had a nuclear explosion at Chernobyl, and it leaked all over northern Europe. But how many people actually died from it?” The number he gives is around 4,000. (Some estimates are substantially higher; calculating the long-term damage across a continent, and incorporating myriad other factors, is inherently nebulous work.) Compared with the casualties of the coal industry, he argues, it’s minuscule.

Sulichin, meanwhile, is keen to distance the image of nuclear energy from the idea of mushroom clouds and bombs. “People confuse nuclear energy with nuclear weapons – they have nothing to do with each other. They come from the same origins, but it’s not the same. One thing is to power, the other to create mass destruction.”

Stone speaks highly of Russia’s nuclear investment, its commitment to building new reactors and exporting them to “third-world countries”. For Stone, the West’s “political problems” with Russia (and China, which is also showing signs of nuclear intent) are obstacles to progress. “All the world’s political disputes are complicated,” he says. “We were really looking at the big picture here. We’re trying to say, look, we’re in this together.” Last November, the UK pledged £700m of backing to the major new Sizewell C nuclear plant on the North Sea coast, pushing China, which had previously been a sizeable stakeholder, out of the deal.

Following the release of The Putin Interviews in 2017, Stone was branded a Putin apologist; he has praised the dictatorial Russian leader on multiple occasions, though he has criticised some of his actions since the war with Ukraine. “At that time, Putin was the so-called enemy,” Stone says. “And our theory was, ‘Let’s know the enemy.’” He describes the four-part series, pruned from 30 hours of interviews with the Russian president, as an “invaluable” resource for studying the man.

“We were the first English-speaking series to actually let [Putin] speak in his own voice,” Stone says, with a hint of accomplishment. “If you look at the American things they do on him, it’s always dubbed like bad Italian cinema from the 1950s. They get an actor who does his voice as a gruff, growly Russian bear, which he’s not – he’s the opposite. A very refined individual who speaks quietly, reasonably.”

Finding the initial financing and, later, distribution for Nuclear Now was arduous. The damage The Putin Interviews did to Stone’s reputation in the West was considerable; it’s fair to assume this was part of the reason Stone and Sulichin had trouble getting Nuclear Now off the ground. But it was by no means the only reason. They argue that the dominance of Netflix-style “true crime” series is stifling the ecosystem, keeping out more heavyweight non-fiction fare.

“Killers are what’s popular,” Stone says. “The Tiger series [Tiger King]. But they don’t take the kind of subject matter that is geopolitically important. I think there’s a bias, and I think they’re worried about the entertainment value on nuclear issues. You know – ‘Where is the star?’”

For nuclear advocates, though, there are shoots of optimism. Sulichin points to a new wave of eco-conscious celebrities who seem less hostile to nuclear causes, such as Leonardo DiCaprio. “I guess public opinion is starting to tip,” he says. “When we were doing the film, it was very difficult to finance, because of the bad reputation of nuclear, and the missing information. People didn’t want to even listen to what we had to say. But now, because of scientific evidence, things are starting to tip.”

Nuclear Now is convincing, but sceptics from both sides of the eco-political spectrum have disputed some of its assertions. For swathes of the population, when it comes to nuclear energy, the jury is still out. But the time for deliberation is slipping through all of our fingers.

‘Nuclear Now’ will be released in the UK later this year