Scientists in Australia have discovered a new species of shark with bizarre, human-like molars that it uses to smash down on prey.

The new species, named painted hornshark (Heterodontus marshallae), is part of the order Heterodontiformes, which are classified by their unique body shape and small horns that protrude from above their eyes.

"This order of sharks resembles fossils of long extinct sharks due to similar morphology, including spines. But we know now they’re not closely related," Helen O’Neill, a fish biologist at the Australian National Fish Collection (ANFC) part of the Australian government agency CSIRO, said in a statement.

The newly described species is only found in the waters of northwest Australia, roughly 410 to 751 feet (125 to 229 meters) below the surface, according to a study published July 12 in the journal Diversity.

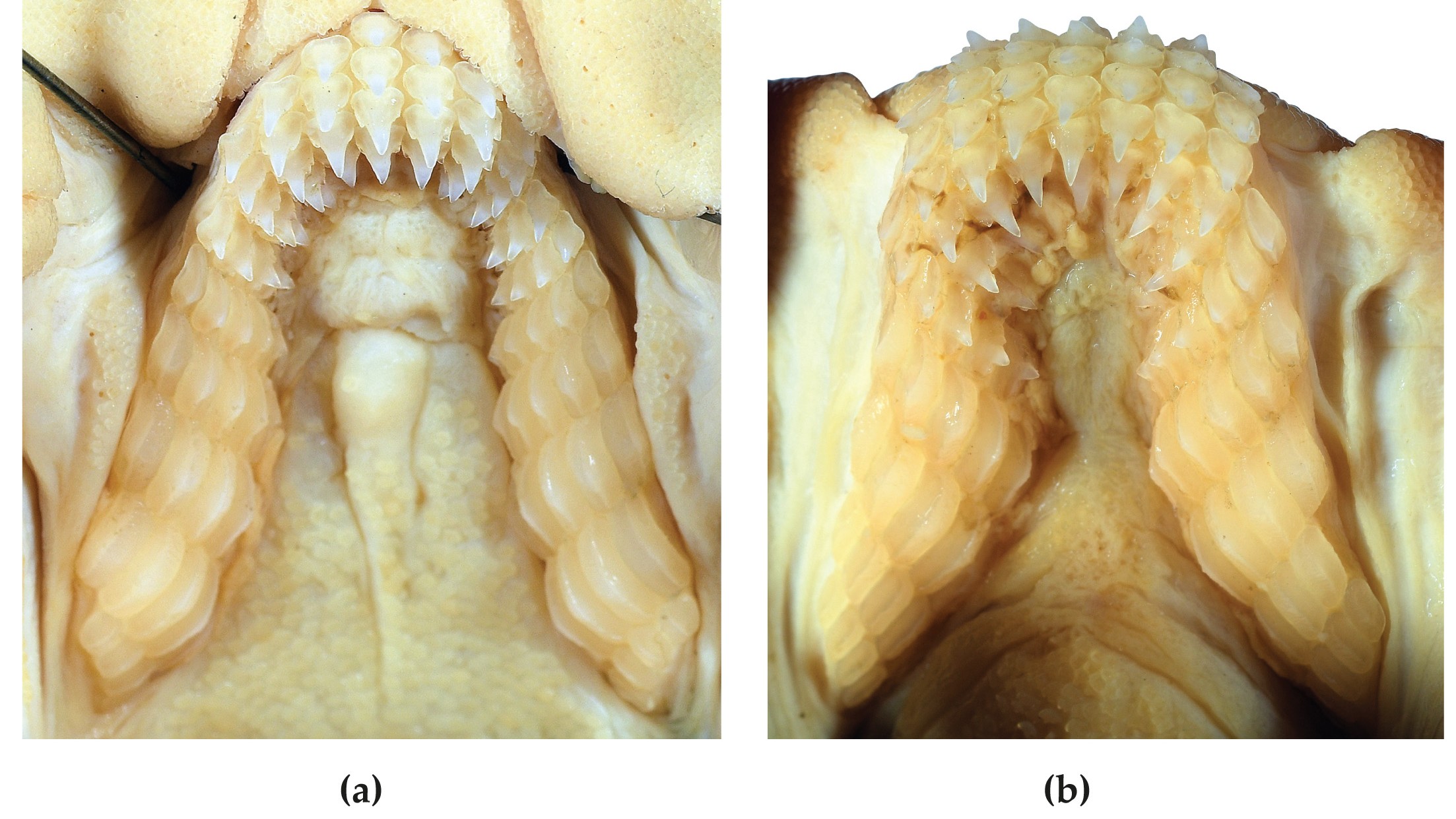

They have several rows of teeth and an extremely large jaw relative to their skull, which enables them to snack on creatures like molluscs and crustaceans.

"The teeth of all of the hornshark species are very similar to each other, but hornsharks as a group have very different teeth to most other sharks. [They] have grasping teeth near front and large molar-like teeth as you move back along the jaw," Will White, a senior curator of the ANFC and co-author on the study, told Live Science in an email. "This group has evolved to crush heavy shelled prey utilising its molar-like teeth."

Related: What is the deadliest shark attack ever recorded?

In November 2022, the researchers were surveying seabed habitats in Gascoyne Marine Park in Western Australia when they caught an adult male H. marshallae that was about 1.75 feet (53 centimeters) long when measured from the tip of its snout to its tail fin.

"Compared to other Australian hornsharks, this species has a distinctive striped pattern," White said. "This pattern is very similar to the Zebra hornshark and was previously thought to be the same species."

However, zebra hornsharks (H. zebra) are found in shallower waters and normally live near Indonesia or Japan, while H. marshallae prefer the deeper ocean surrounding Australia's coast. Prior to the 2022 expedition, the researchers had examined six specimens and an egg casing of what would later be identified as H. marshallae from museum collections around Australia, and they were in the process of classifying this new species when they stumbled upon the living male.

“We have a female specimen in our collection, but the one we collected during the voyage is a male," O’Neill, who was also a co-author on the study, said in the statement. "We prefer to use males for shark holotypes because they have claspers, which are external reproductive organs that can vary between species and help us tell them apart."

Researchers last described a shark species from the order Heterodontiformes in 2005, and scientists are skeptical that they will find any more of these underwater predators, White said.

"This order of sharks and very distinctive in their large head, crests above eyes and spines in front of dorsal fins," he said. "My gut feeling is that we would have seen specimens of such a distinct species since they are mostly shallow water… where exploration has been substantial in most places. I could just as easily be wrong though."