Emmy Rākete responds to a profound new vision of Tāmaki Makaurau, shortlisted for tomorrow's Ockham awards

Once, as a teenager, I watched a team of workers cut into the road outside my bus stop. Day by day, with saws in hand and then with shovels, diggers, with more exotic surgeon’s tools, they peeled away the asphalt. Roads are boring to most people, excepting internet-poisoned public transport enthusiasts. This road wasn’t. When the team dug through the asphalt they hit an older layer of paving, its archaic traffic markings still intact. Below that, deeper in the dirt-packed wound, capillaries of phone and power cables. Orange pipes I didn’t know the purpose of. One lunch break - sneaking off, like all naughty teenagers do, to huff menthol cigarettes on my own - something new was bared, raw and exposed in the wavering heat. An incongruous surface of brick. Auckland’s skeleton, the spine of Queen Street. This was the so-called Ligar Canal, a putrid gutter that had once run the length of the colonial city’s main street, flowing thick with sewage and waste before it was bricked up and buried.

And of course, the canal didn’t come from nowhere. Before there was an Auckland, there was a river. Waihorotiu, flowing from uptown to the sea. The incision these workers had made in the road didn’t just open up space. It opened up time. Auckland cannot but remember itself. Lucy Mackintosh’s Shifting Grounds: Deep Histories of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland [shortlisted for the best book of illustrated non-fiction at the Ockham awards; the winners are announced tomorrow night] is a book concerned with this remembering, attentive to how understanding Auckland spatially lets us understand it historically.

So what is Auckland, then? It would be easiest to say it is the surface, the place we experience every day. As Mackintosh explains, this is how the historical tradition has generally understood Auckland. Histories of the city have always been brief and blunt, concerned only with a specific period or place. This approach to history, though, limits our ability to understand somewhere like Auckland. In 2021 my partner and I returned from the outskirts of Auckland to its central isthmus, where I was raised, to raise our daughter. Certainly, there are physical features in the area which remain from my childhood — the KC Loo’s Fruit Centre, or the Pizza Hut buildings reinhabited by new businesses like hermit crabs.

But as the Marxist geographer Neil Smith argued in his work Toward a theory of gentrification, neighbourhoods will not be allowed to simply lie fallow. Instead, as the capital invested in buildings depreciates in value, the gap between the actual and potential rent which the landlord class could charge on a given section of land grows intolerably wider. The outcome is a slow but inexorable motion across capitalist cities. Capital is invested into areas where it is relatively diffuse, allowing the wealthy to profit from this rent gap at the cost of driving out anyone unable to afford the higher rents. Rivers become canals, which become roads. The process of development and redevelopment impedes our historical vision, Mackintosh notes, because so little actually remains visible. Like the noble road workers, she bores through the developmental strata in order to make Auckland comprehensible.

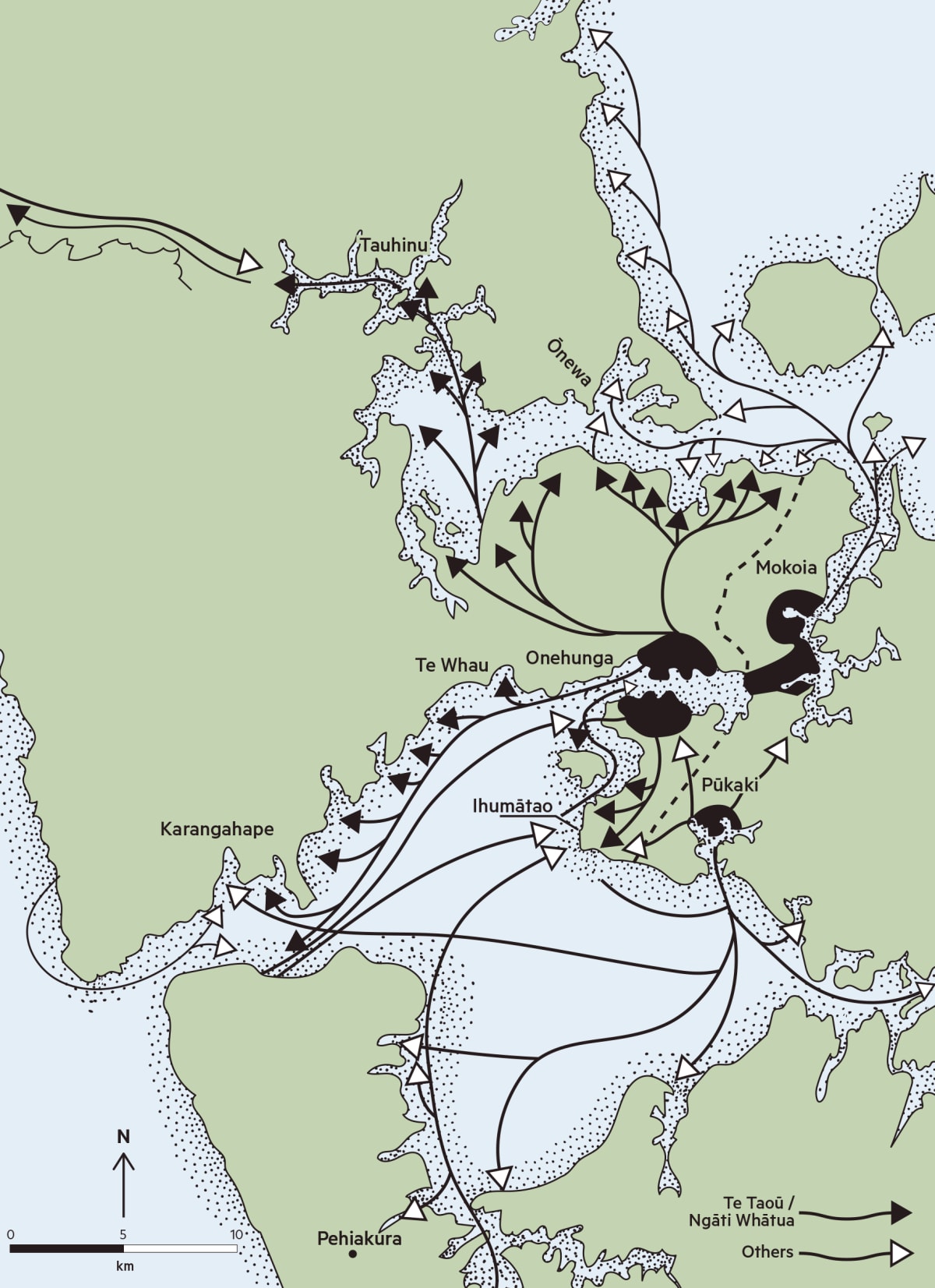

Shifting Grounds cuts Auckland open in a number of places, centering itself on three main sites: Ihumātao, Pukekawa/ Auckland Domain, and Maungakiekie/ One Tree Hill. With the possible exception of the Ōtuataua Stonefield at Ihumātao, these are not unfamiliar places to most Aucklanders. Even Ihumātao, remote by Auckland’s standards, was temporarily home for thousands of us during the victorious struggle to defend the land from Police and developers. The book is not a history of somewhere far-off, where it would be unsurprising to be surprised. I know that I don’t know anything about Latin America, for example, and so I expect for a book about the CIA’s blood-drenched history there to change my perception of the region. Like most Aucklanders, I am at least begrudgingly familiar with this city. I thought that I knew it. Shifting Grounds relentlessly, page after page, demonstrates that I didn’t. I knew Auckland the way that I knew Queen Street. It had to be cut open for me before I understood.

In every location, Mackintosh begins with the pre-human story of Auckland, concerned with the uncaring tectonic forces that have made it. This is the first thing schoolchildren learn about Auckland — an enthusiastic teacher or hairy-chested Department of Conservation worker will point to some rock and say oh, did you know this rock was blown all the way here from Rangitoto, or wherever, and you’ll nod, because the distances and forces involved simply exceed your eleven year-old capacity for thought. With surveyor’s maps, aerial photos, and clear, measured description, Mackintosh explains the formation of Auckland in a way that is completely comprehensible. Not just abstract volcanoes blowing out abstract quantities of lava abstract distances. These are the volcanoes, this is the lava field, here is a photo of the exact place. Shifting Grounds never just assumes that the reader is familiar with geography, but like a good teacher, explains throughout from basic principles how Auckland’s landscapes were formed.

Here, as throughout the book, Mackintosh is trying to demonstrate how things which might seem like fixed substances are actually contingent, taking their shape depending on the outcome of a number of factors. In Auckland even the hills, she shows us, are a work in progress.

Mackintosh is attentive to geography not just out of some sense of academic curiosity. In each of the locations in which Shifting Grounds is interested, Mackintosh lays out the geological history of Auckland so that she can explain its connection to human history. Mackintosh is particularly attentive to the role that Auckland’s environment has played in the process of production. This sort of ugly, technical term I’ve yanked from Karl Marx refers to all of the work necessary to make daily life for a society possible in the long run. We would all die without food, for example, and so to understand a society you probably need to understand how it produces and consumes food, and so on.

For example, Shifting Grounds discusses how Ihumātao’s geological history made it an ideal location for the Māori agricultural process. The planet, with its volcanic spasms, shaped the land, and the land shaped the people. The process of production in Māori society depended on kūmara agriculture, and Ihumātao is a kind of plant lab for kūmara cultivation, a fertile and rocky lava plain laid out thousands of years before the Polynesian diaspora even left Asia. The human history — who had usage rights of the land, when to harvest, what crops should be planted — is not easily separable from the inhuman history. Shifting Grounds is about reading them together.

Everywhere she goes in Auckland, Mackintosh slyly flips the city upside-down. Often, this means baring the colonial project’s rear end. She relates an extended story about a settler’s attempt to farm Puketūtū Island in which his cattle drown, his wife is shipwrecked, his pigs eat his lambs, the dogs he brings in to drive off the pigs also eat the lambs, and his entire farm is finally burned to the ground. The anecdote might have been out of place in a drier history text, but here it’s perfect.

For all that Auckland is sometimes thought of as an outpost of Western civilisation in the Pacific, an exemplar of European mastery over the wilds, stories like this one provide a more grounded evaluation of these ideas. In this period, settlers were barely capable of providing for themselves. The early city, Mackintosh notes, relied on the purchase of crops grown by Māori in order to feed itself. As the process of land theft accelerated, and especially after the 1863 proclamation that Māori either swear loyalty to Britain or leave Auckland, the colony came more and more to rely on populations considered exterior to it. Plugging the gap left by the expulsion of Māori from Auckland, Mackintosh explains, the city depended on the labour of Chinese migrants on the Ah Chee family’s plots in Pukekawa to produce the food it needed. The nominally European economy of Auckland has always depended on the underpaid labour of people that it broadly considered to be subhuman. Shifting Grounds is constantly unsettling broad assumptions we hold about Auckland’s history.

I feel a sort of cynical affection for this city. The feeling comes from resigned familiarity, a sense that I know this place’s rhythms. Auckland is where the contradictions of capitalism reach their most absurd heights, where men in tailored suits natter about spreadsheets while families cram into garages to sleep. Making Auckland your home is like pushing on a bruise, picking a scab. Shifting Grounds serves as a reminder that accepting all this pain as some cruel cosmic fact is just complacency. The book’s purpose is to defamiliarise Auckland, to take everything you assume to be true about the city and show you that it didn’t have to be that way. Pukekawa was covered in ferns, a volcanic cone just barely forced into the semblance of a British lawn by a painstaking process of burning, planting, and earthworks to flatten it all out. Te Wherowhero, who would become arikinui of the Kīngitanga, lived for years in Auckland and worked to try to maintain the balance of power between Māori and Pākehā. At Ihumātao, immense gardens provided for generations of people who were born, lived, and died here. The Acclimatisation Society, bungling as always, tried to establish a wild monkey population. On Maungakiekie, even under the shadow of the obelisk memorialising our ‘dying’ race, an immense burial cave still protects the bodies of hundreds of ancestors. All of it is happening all at once. Shifting Grounds has laid all these strata bare.

For days after reading Shifting Grounds, I was haunted by double-vision. The city as it is, and the city that could have been. Auckland’s maunga were pā, and now I see the hillsides twice — I see the Māori city, the place loved by so many, and I see the ruins left to us by the process of colonisation. Every part of the city now crackles with contingency, with the historical factors that shaped it and the certainty that it could have been different. The double-vision it has given me is why Shifting Grounds isn’t a depressing post-mortem. Mackintosh isn’t dissecting some dead things to reveal the inevitability of its decline, to show how terminal its illness had been.

With Shifting Grounds, Mackintosh is stripping back the city’s apparent solidity to show us how unstable it all is. This place was made. If Auckland is a city not intended for people, a place for investment capital to appreciate in value and where human life is an afterthought at best, it is because somebody did that. None of it was inevitable. The river need not have flowed in that direction. The city need not have used the river as a sewer. The canal need not have been bricked over. Queen Street need not have been built over the canal. Seeing the surface of the road excavated was not a lesson in inevitability for me, and neither was reading Shifting Grounds. Mackintosh has written a history of Auckland that gestures to other possible histories, other possible Aucklands. Walking the ruins of this city with my daughter, I can tell her now about the city still yet to come. The Auckland in which she will live, the Auckland in which it will be possible for her to live.

Shifting Grounds: Deep Histories of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland by Lucy Mackintosh (Bridget Williams Books, $60) is shortlisted for best book of illustrated non-fiction at tomorrow night's Ockham book awards, and is available in bookstores nationwide. It's among the 16 books shortlisted for the Ockhams which are all offered in an incredible prize giveaway exclusive to ReadingRoom. Entries close at 6pm on Wednesday.

Tomorrow in ReadingRoom: we continue our week-long coverage of the Ockhams with an important story on what one of the finalists will be wearing to tomorrow night's ceremony at the Q Theatre in Auckland.