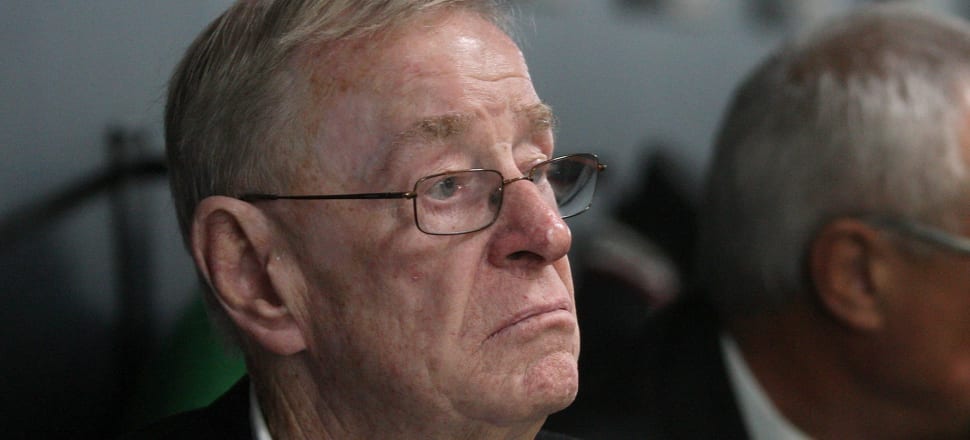

Ken Douglas, a colossus within New Zealand’s economic and political history, died this week aged 86.

Ken Douglas was born in 1935 to a truck driver father and a seamstress mother, in the brief interval between global depression and global war.

He was a working class boy who grew to become the leader of New Zealand’s union movement. With his pock-marked features, rumpled jerseys, unruly hair and unpolished but compelling oratory, he seemed the archetypal labour leader.

But his was also a life of confounding contradictions. As a young truck driver in the 1950s, he thought the Wellington Drivers Union was a ‘leech on workers’ backs’ – but by age 23 he was leading it and helping to build it into a militant industrial force.

In a labour movement that had relied for decades on the statutory prop of compulsory union membership, Douglas opposed it, believing that it weakened the cause of organised labour.

He was a scrapper and a life-long Marxist, but Tory politicians respected him and saw him as someone they could do business with. Jim Bolger, Minister of Labour from 1978 to 1984 – a period of long and bitter strikes – found Douglas to be a “good bloke” and a pragmatist. It was an era of frequent late-night meetings in the Beehive between labour minister, employers and union bosses seeking settlements to end this or that industrial war. “If Ken was involved on the union side, you knew you would resolve it”, said Bolger.

Outraged in 1960 by the Government’s and the NZ Rugby Union’s complicity with South Africa’s apartheid regime in agreeing to an All Black tour that excluded Māori, Douglas joined the Communist Party. Later, when the party split, he helped form the Soviet-aligned Socialist Unity Party.

But he was no revolutionary. He wanted a better form of capitalism that worked for working people, and invested immense political effort into trying to address New Zealand’s productivity crisis, long before mainstream economists had begun concerning themselves with the issue.

Rob Campbell, Douglas’s protege and the man once tipped to succeed him as the leader of the union movement, describes his mentor as a man “with a sharp mind and determined, almost physical, dedication to the interests of working people”.

Douglas “was ahead of his time”, says Campbell. “He saw the implications of things further down the track. He saw the way that the position of working people was weakening.”

He knew that “if we can’t progress through productivity, capital will try to progress simply through exploitation”, says Campbell, who left the union movement in the 1980s for the corporate world and now chairs Te Whatu Ora/Health New Zealand.

Rise to the top

From his base at the helm of the Wellington Drivers’ Union, Douglas’s influence in the wider labour movement strengthened. In 1979 he became secretary of the Federation of Labour (FOL), under the presidency of old-school unionist Jim Knox. These were days of deepening economic malaise for New Zealand, under the premiership of Rob Muldoon. Inflation was raging, and the consensus that had held the tripartite, state-sponsored system of wage fixing was failing. In a desperate move, Muldoon in 1982 imposed a wage price freeze (which soon became merely a wage freeze). It remained in place until after the election of the Fourth Labour Government in 1984.

The radical restructuring and savage job losses undertaken in the name of Rogernomics put enormous stresses on the unions, not least because it was being done by the political wing of the labour movement.

But Douglas believed there also needed to be deep reform within the union movement.

Work began to merge the private sector unions (represented by the FOL) and the public sector unions (represented by the Combined State Unions) into a single peak body. That was achieved in 1987, and Douglas was voted in as the inaugural president of the new Council of Trade Unions (CTU), representing the interests of 650,000 workers.

Douglas and supporters worked through the 1980s to get tripartite support for a new pay fixing system that linked wage rises to productivity. In 1990, during the last gasp of the Fourth Labour Government, then-prime minister Mike Moore embraced the idea and signed a deal with the CTU known as the Compact. It limited pay rises to 2 percent, with bigger pay hikes needing to be linked to productivity gains. In exchange for pay restraint, low-paid workers would be protected from government spending cuts and unions would get more say on economic policy.

Through those years Douglas had also championed union amalgamations, in the hope of consolidating the large number of small occupation-based unions into industry-based groups that would have the scale and resources to be strategic partners with industry and government in skill development, research, and productivity.

He also strongly backed education and training for worker representatives. Hazel Amstrong, who was heavily involved in this work through the government-funded Trade Union Education Authority (TUEA), said Douglas wanted unions to have “well-informed delegates and health and safety representatives who could foot it around the bargaining table, understand company balance sheets, productivity, health and safety and the like. He had a vision.”

From the vantage point of 2022, with poor productivity still New Zealand’s ongoing achilles heel, Douglas’s linkage of pay, tripartite policy-making and productivity looks radical and far-sighted.

But in late 1990 it was doomed. The Employers Federation immediately dismissed the proposal. The Business Roundtable condemned it as Keynesian (a heinous offence in the mind of the Roundtable’s boss, Roger Kerr). Many unionists were deeply suspicious of a scheme that would keep base pay rises well below a rate of inflation that was running at 5 percent.

And then the Government changed. Under Bolger’s National Party leadership, and driven by the evangelical organising of the Business Roundtable, the Employment Contracts Act (ECA) was introduced in 1991. The Compact had no place in the new order.

Nor, indeed, did unions.

The ECA was a scheme to atomise pay bargaining down to the level of the individual worker; far from embracing strong and well-resourced unions in a collaborative model to build productivity and skills, the new regime aimed to remove collective labour from the scene.

TUEA – seen by the new government as pushing an ideological agenda – was also wiped out.

Many unionists demanded a national general strike to oppose the ECA, which presented a clear existential threat to the movement. But Douglas, the craggy, one-time militant, demurred. He believed it would be little more than a “protest parade” that would do nothing to overturn the Bolger Government’s policy. At a meeting of the CTU’s affiliates, a motion for a general strike was voted down.

Douglas’ decision not to lead a more forceful resistance earned him life-long enemies and enduring bitterness from some who still accuse him of selling out the working class.

Even union centrists like Douglas’s CTU successor Ross Wilson think he was wrong. Workers from Wilson’s own Harbour Workers Union were among those who were ready to participate in a general strike, “but [Douglas] wasn’t prepared to lead the union movement into defeat”.

Peter Harris, who worked alongside Douglas for years as the CTU’s economist, dismisses as a “romantic fantasyland” the notion that a general strike could have changed the course of history.

Harris says the job of Douglas and the CTU during the 1990s, as the ECA stripped unions of their membership and denied most workers the ability to collectively bargain, was to prevent the movement from falling into total collapse, so that it could rebuild when the law was repealed under a future Labour government.

“We’ve got a pick-axe and we’ve got to hang on to the cliff,” he says of the perilous state the movement was in. “One slip and we’re dead. And I would say at the end of Ken’s time that unions still existed, unions had resources, and unions had the capacity to rebuild.”

Harris’ summation of Douglas’ legacy through the 1990s is moot. Some – including Harris himself – think the collapse of the USSR in 1991 meant the Soviet-aligned communist “lost his anchor”. He began putting more of his legendary energy into the international union movement, where he was well respected and influential. But within his own movement at home, some thought he seemed disillusioned with his own affiliates, and that after a decade of crisis for the movement he had lost the energy to bring strong leadership.

Outgoing International Labour Organisation director general Guy Ryder says Douglas was determined to “ring the alarm bell” globally about the ECA, which represented a sophisticated and far-reaching form of attack on collective rights. Ryder, then a young official in the international union movement, assisted Douglas in developing a case against the Government to the ILO, which in 1994 found in the CTU’s favour that the law did violate key international conventions by failing to promote collective bargaining.

“Ken’s insights really were impressive,” says Ryder. “He really saw that the ECA was not only a danger to the way New Zealand trade unions had operated in collective bargaining, I think he saw quicker than most that this was the beginning of an unfurling wave of neo-liberal attacks on trade union rights globally.

“You have to put it in the moment – it was the end of the Cold War, end of the Soviet Union - and here were New Zealand employers coming with a fairly difficult-to-understand on the international stage way of dismantling collective bargaining arrangements, and going to individual contracts. I think Ken very quickly realised...that this was something that might appear on the international scene in a pretty insidious way.”

To the boardroom

As the 1990s wore on there were battles to prevent further labour market reform to weaken entitlements under the Holidays Act, but Douglas and his CTU colleagues were noticeable by their absence from the front line. Morale in the movement was low and frustration high.

In 1999 Douglas retired, and Wilson was elected in his place.

His services were acknowledged when, in 1998, he became a member of the Order of New Zealand – the nation’s highest honour.

With a Labour-led government in power from late 1999, the old communist put down his hammer and sickle and joined the Labour Party.

But Marxism continued to be the frame of reference through which he analysed the world – even as he pursued a new career as a director of major companies including New Zealand Post, Air New Zealand and Health Care New Zealand. He also served on the boards of the New Zealand Rugby Union, Asia 2000 Foundation, Trade NZ, and as a Porirua City Councillor.

At New Zealand Post, he was back alongside his old sparring partner, Jim Bolger. But there was never any spouting of ideology or class war, just the same pragmatism Bolger had seen decades earlier in the thick of strikes and lockouts. “He was a very, very good director, and a good person to work with.”

Douglas’s biographer, David Grant, writes in his 2010 Man for all Seasons that the move from the helm of the union movement to the corporate world was neither a sellout nor an ‘add on’. Instead, he argues Douglas’s post-union career in commercial governance – wherein his analytical mind and strategic thinking was held in high, “almost obsequious”, regard – was not a rupture from his past philosophy, but a continuation of it.

He brought to it “the same intensity, energy and experience, into new, different and challenging contexts,” writes Grant. “He has learned to combine his socialist heart with the wisdom and experience he has gained from working over the years with a wide range of people in often radically different circumstances.”

Douglas told Grant that an organisation is successful only when it overcomes the contradictions of marrying capital, technology and labour.

“It is not an accommodation of one over the other,’” he told the biographer. “We are all there for a shared purpose. Nothing is black and white.”