Capturing carbon dioxide from the air or industries and recycling it can sound like a win-win climate solution. The greenhouse gas stays out of the atmosphere where it can warm the planet, and it avoids the use of more fossil fuels.

But not all carbon-capture projects offer the same economic and environmental benefits. In fact, some can actually worsen climate change.

I lead the Global CO₂ Initiative at the University of Michigan, where my colleagues and I study how to put captured carbon dioxide (CO₂) to use in ways that help protect the climate. To help figure out which projects will pay off and make these choices easier, we mapped out the pros and cons of the most common carbon sources and uses.

Replacing fossil fuels with captured carbon

Carbon plays a crucial role in many parts of our lives. Materials such as fertilizer, aviation fuel, textiles, detergents and much more depend on it. But years of research and the climate changes the world is already experiencing have made abundantly clear that humanity needs to urgently end the use of fossil fuels and remove the excess CO₂ from the atmosphere and oceans that have resulted from their use.

Some carbon materials can be replaced with carbon-free alternatives, such as using renewable energy to produce electricity. However, for other uses, such as aviation fuel or plastics, carbon will be harder to replace. For these, technologies are being developed to capture and recycle carbon.

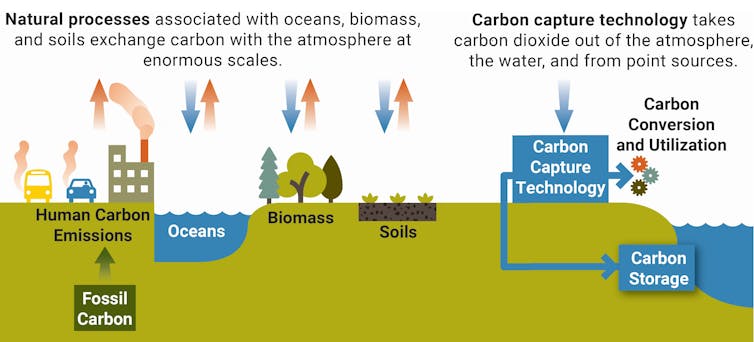

Capturing excess CO₂ – from the oceans, atmosphere or industry – and using it for new purposes is called carbon capture, utilization and sequestration, or CCUS. Of all the options to handle captured CO₂, my colleagues and I favor using it to make products, but let’s examine all of them.

CCUS best and worst cases

With each method, the combination of the source of the CO₂ and its end use, or disposition, determines its environmental and economic consequences.

In the best cases, the process will leave less CO₂ in the environment than before. A strong example of this is using captured CO₂ to produce construction materials, such as concrete. It seals away the captured carbon and creates a product that has economic value.

A few methods are carbon-neutral, meaning they add no new CO₂ to the environment. For example, when using CO₂ captured from the air or oceans and turning it into fuel or food, the carbon returns to the atmosphere, but the use of captured carbon avoids the need for new carbon from fossil fuels.

Other combinations, however, are harmful because they increase the amount of excess CO₂ in the environment. One of the most common underground storage methods – enhanced oil recovery – is a prime example.

Underground carbon storage pros and cons

Projects for years have been capturing excess CO₂ and storing it underground in natural structures of porous rock, such as deep saline reservoirs, basalt or depleted oil or gas wells. This is called carbon capture and sequestration (CCS). If done right, geologic storage can durably remove large amounts of CO₂ from the atmosphere.

When the CO₂ is captured from air, water or biomass, this creates a carbon-negative process – less carbon is in the air afterward. However, if the CO₂ instead comes from new fossil fuel emissions, such as from a coal- or gas-fired power plant, carbon neutrality isn’t possible. No carbon-capture technology works at 100% efficiency, and some CO₂ will always escape into the air.

Capturing CO₂ is also expensive. If there is no product to sell, underground storage can become a costly service ultimately covered by taxes or fees, similar to paying for trash disposal.

One way to lower the cost is to sell the captured CO₂ for enhanced oil recovery – a common practice that pumps captured CO₂ into oil fields to push more oil out of the ground. While most of the CO₂ is expected to stay underground, the result is more fossil fuels that will eventually send more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, eliminating the environmental benefit.

Using captured carbon for food and fuel

Short-lived materials made from CO₂ include aviation fuels, food, drugs and working fluids used in machining metals. These items aren’t particularly durable and will soon decompose, releasing CO₂ again. But the sale of the products yields economic value, helping pay for the process.

This CO₂ can be captured from the air again and used to make a future generation of products, which would create a sustainable, essentially circular carbon economy. However, this only works if the CO₂ is captured from the air or oceans. If the CO₂ comes from fossil fuel sources instead, this is new CO₂ that will be added to the environment when the products decompose. So even if it is captured again, it will worsen climate change.

Storing carbon in materials, such as concrete

Some minerals and waste materials can convert CO₂ to limestone or other rock materials. The long-lived materials created this way can be very durable, with lifetimes of longer than 100 years

A good example is concrete. CO₂ can react with particles in concrete, causing it to mineralize into solid form. The result is a useful product that can be sold instead of being stored underground. Other durable products include aggregates used in road construction, carbon fiber used in automotive, aerospace and defense ]applications and some polymers.

These materials provide the best combination of environmental impact and economic benefit when they are made with CO₂ captured from the atmosphere rather than new fossil fuel emissions.

Choose your carbon projects wisely

CCUS can be a useful solution, and governments have started pouring billions of dollars into its development. It must be closely monitored to ensure that carbon-capture technologies will not delay fossil fuel phaseout. It is an all-hands-on-deck effort to take the best combinations of CO₂ sources and disposition to achieve rapid scaling at an affordable cost to society.

Because climate change is such a complex problem that is harming people throughout the world, as well as future generations, I believe it is imperative that actions are not only fast, but also well thought out and based in evidence.

Fred Mason, Gerry Stokes, Susan Fancy and Stephen McCord of the Global CO₂ Initiative contributed to this article.

Volker Sick receives funding from the Grantham Foundation for the Preservation of the Environment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.