"Comedy expresses the foolishness of the human condition," said Norman Lear. "Humor makes it possible to see our biggest social issues."

He transformed the situation comedy from a vehicle for cheap, screwball gags into a medium for profound reflection.

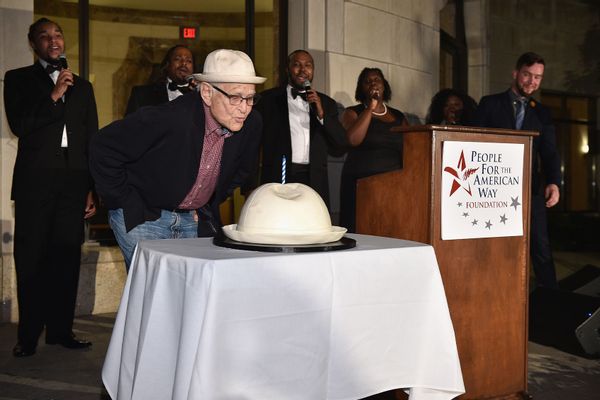

Lear shared that observation with Salon shortly before his 100th birthday on July 27, 2022. As a centenarian, he has now lived through a full quarter of the 400-year culture war that has bloodied America's history. Widely known for creating some of the most groundbreaking sitcoms ever broadcast, from "All in the Family" to "The Jeffersons," Lear devoted his entire comedic life to amplifying the voices of Americans who have historically been stifled.

In the 1970s, when American television was still full of white middle class stories, Lear centered Black narratives, integrated Puerto Rican and queer characters into his stories, depicted interracial relationships, and introduced provocative subjects like racism and abortion into the primetime landscape. One of the first inductees into the Television Hall of Fame, he transformed the situation comedy from a vehicle for cheap, screwball gags into a medium for profound reflection.

Lear toiled as a television writer throughout the repressed 1950s and early 1960s, becoming a gifted technical craftsman who mastered the form. It wasn't until the early 1970s, however, when America was erupting with wave after wave of progressive identity movements, that he started to find his real voice. Against a backdrop of resurgent feminism, Black Power, Puerto Rican pride, and the Stonewall Riot, he produced "All in the Family," a sitcom that changed television forever by holding a mirror up to America.

"Norman spoke out," actor and director Rob Reiner, a key member of the "All in the Family" cast, told Salon. "He taught me to do the same."

Architecting the Archie-Verse

Premiering in 1971, the show heard 'round the world gave voice to the sort of intense political debates that were happening in living rooms all over the country. Inspired by a British program, "Till Death Us Do Part" that features "a bigoted father and a liberal son who argued about everything under the sun," as Lear wrote in his memoir, "All in the Family" depicts Archie Bunker (Carroll O'Connor), an avatar for aggrieved white male ignorance, in comedic combat with his wife Edith (Jean Stapleton), their daughter Gloria (Sally Struthers), and Gloria's husband Mike, played by Reiner.

"Norman spoke out. He taught me to do the same." – Rob Reiner

The show's scandalous pilot features a heady mix of sexual innuendo, Christian vs. atheist antagonism, and a raft of racial slurs. CBS, which picked up the series only after ABC had twice rejected it, tried to stave off any controversy by airing a disclaimer before the first episode. "'All in the Family,'" they wrote, "seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show — in a mature fashion — just how absurd they are."

The initial critical response was mixed. Variety dubbed the show "the best tv comedy since the original 'The Honeymooners,'" but critic John Leonard, writing for Life, suggested the show ought to be exterminated with roach spray. Some viewers thought "All in the Family" was a scathing satire of conservative values, while others thought it was just plain bigoted. By the end of its first season, though, the show was an unqualified success, earning scores of Emmy Awards and nominations.

Lear, however, was just getting started. Over the next five years, he created an Archie-verse of kindred series and interconnected spinoffs that captured the 1970s zeitgeist and remained popular until 1994, when "704 Hauser," the last direct "All in the Family" spinoff, went off the air. Never in television history has a producer achieved the same feat of sustained creativity. Even the vaunted Marvel Cinematic Universe (which now has invaded our small screens) would have to continue for another 14 years to match Lear's record.

First up after "All in the Family" was "Sanford and Son," a vehicle for comedic superstar Redd Foxx that recreated the Bigoted Old Man vs. The World formula in the context of a Black family. Foxx played Fred Sanford, who owned and ran a junkyard with his son Lamont (Demond Wilson).

While Lamont was friends with the Sanfords' Puerto Rican neighbor, a recurring character named Julio Fuentes (Gregory Sierra), Fred harbored deep prejudices that allowed the show to celebrate Black culture and portray the difficulties of life in Watts without sacrificing the complexities of racism and generational conflict.

Next came "Maude," a direct "All in the Family" spinoff featuring Edith's feminist cousin Maude Findlay. The late Bea Arthur, a former Marine Corps Women's Reservist during World War II, brought toughness to the title role. The series introduced substance abuse, mental health, and the struggles of women in the 1970s workplace into American entertainment at a time when they were barely spoken about publicly. The writing was as unflinching as Maude herself, asking hard questions and honestly portraying a wide range of perspectives.

Maude's maid, Florida Evans (Esther Rolle), then got her own show as well. "Good Times" was the first spinoff of a spinoff in television history, and it was also the first sitcom to depict a two-parent Black family. While Jimmy Walker's goofy portrayal of Florida's son J.J. Evans, along with his character's "Dyn-o-mite" catchphrase, stole the show a bit and captured the public imagination, "Good Times" was more than a series of gags. It confronted contemporary issues without easy solutions, like systemic racism in education and the need for criminal justice reform.

In the wake of his first three successes, Lear arrived at his office one day to find it occupied by members of the Black Panthers. They were intent on asking him why he only made shows featuring poor Black characters. "Sanford and Son," after all, was set in a junkyard, while "Good Times" took place in Chicago's Cabrini Green housing project.

Lear knew they were right to challenge him, and he knew just what to do about it, too. In short order, the Bunkers' affluent Black neighbors, George and Louise Jefferson (Sherman Hemsley, Isabel Sanford), moved on up to a show of their own. "The Jeffersons" became the most successful of Lear's "All in the Family" spinoffs: the second-longest-running series in television history featuring a Black family.

Lear's new show was also the first series in television history to feature an interracial couple, the Jeffersons' next-door neighbors, Tom (Franklin Cover) and Helen Willis. When Roxy Roker was cast in the role of Helen, Lear took her aside to warn her about the firestorm that would no doubt ensue. Without a word, Roker reached into her purse and pulled out two pictures. One was a portrait taken during her wedding to her white husband, Sy Kravtiz, and the other was a snapshot of her mixed-race son Lenny. She was prepared. She lived the struggle in her everyday life.

Collectively, the shows that made up the Archie-verse recontextualized straight white male supremacy. Every new series Lear produced helped the country learn about and laugh at a new part of itself, and Archie's voice — always the butt of Lear's best jokes — slowly became just one of many different narrative voices in an increasingly diverse television landscape.

"Each spinoff told a different side of contemporary America," Emmy winner Ken Levine, who wrote for "The Jeffersons," told Salon. "His shows were really grounded in reality and reflected America at that time."

After the Archie-verse was established, Lear continued to produce series that humanized the members of marginalized groups. He developed both "One Day at a Time," which centered on a divorced single mother — a television rarity at the time — and "Hot l Baltimore," a show with gay supporting characters that was seen as so provocative the Baltimore affiliate refused to air it.

Even while he focused on breaking new ground, however, Lear remained committed to comedy.

"Norman would do a show that was so issue-oriented and so edgy. He was so incredibly smart to make sure that above all else, the shows were funny," Levine said. "When people tuned in to watch 'All in the Family' or 'Maude' or 'The Jeffersons,' they knew there were going to be laughs in the show, it was not just going to be a civics lesson."

The American Way

By the end of the 1970s, Lear had become a legend, but American political winds started to blow in a different direction. Baby boomers entered their prime earning years, and yippies became yuppies. Ronald Reagan soared into power, marrying the greed of the well-heeled with the racism of the general populace. Groups like the Moral Majority led a cultural backlash to the pride movements of the 1970s, beginning an effort to take over the government and encode conservative values into law.

"Fifty years ago, Norman's People for the American Way was prescient in calling out the Religious Right's attack on our civil liberties," said Reiner. "Sadly, many of his warnings went unheeded."

Lear watched as religious conservatives like Jerry Falwell and Oral Roberts worked to silence voices of dissent and make the United States a monoculture in which some votes were more equal than others. He knew their hate needed to be confronted head-on. Their way, he was convinced, wasn't the American Way, so he created a series of public service announcements in which working Americans and celebrities said as much.

The resulting ad campaign was immensely successful, earning ample press coverage, airtime on the nightly news, and high-profile interviews for Lear. Fueled by the positive reception and concerned about increasing hostility and divisiveness, Lear co-founded the nonprofit People for the American Way to fight right-wing extremism, devoting his creative genius to the organization.

"Fifty years ago, Norman's People for the American Way was prescient in calling out the Religious Right's attack on our civil liberties," said Reiner. "Sadly, many of his warnings went unheeded."

Today, at a moment when cultural discord seems to be escalating dangerously, Lear's steadfast progressive activism deserves to be celebrated.

"Part of what Norman brought to People for the American Way was his skill, talent, and impact using culture and humor to shape how people think about something, to shape a political narrative," long-time staff activist and researcher Peter Montgomery told Salon.

When evangelical groups tried to remove both evolution and the Holocaust from school textbooks, People for the American Way fought back, successfully protecting history and free speech from, as Lear wrote in his memoir, "the fundamentalist zealots who ran the Texas School Board Authority." Televangelist Pat Robertson, furious about the defeat, sent Lear a pointed note.

"Your arms," he wrote, "are too short to box with God."

Clearly, though, they weren't.

As much as the members of the religious right have vilified him, those on the left have always seen Lear differently. "He is a mensch and a warm human being," said Montgomery, who praised Lear's "gut sense of right and wrong, and his gut sense of what the Constitution means, and what is important about America."

King Lear

What initially lit the fire in Lear? His passion for giving voice to marginalized and oppressed people, through both comedy and politics, derived from his relationship with his father. Herman Lear preferred to be called H.K. The "K," he claimed, stood for "King," and he was, indeed, an imperial presence.

He sat in the family's living room on an Archie Bunker-like chair: a throne on which no one else dared sit. Whenever H.K. and his wife Jeanette would argue, the veins in his neck would bulge and he'd yell at her — again, just like Archie — to "Stifle!"

When Lear was eight years old, H.K. was arrested for fraud and sent to prison for five years. Lear's mother and sister moved in with his grandparents, while Lear himself was shuffled from one relative to another, never at home anywhere. He felt perpetually alone — a burden, an outsider — and years later that feeling gave him tremendous empathy for anyone else who felt similarly vulnerable.

If that weren't difficult enough, 1930s radio made Lear feel even more alienated. Father Coughlin, the radio priest whose weekly nationwide broadcast demonized Jews, gnawed at him. He couldn't understand why being Jewish made him a threat to American values. Forever after, the need to combat religious bigots and conservative radio pundits — like Fallwell, Roberts, Robertson, and later Rush Limbaugh — would burn inside him, and today's social media seems to have amplified his anguish.

Lear said, "There are those using social media and the internet, the way Father Coughlin used the radio to spew hate and lies. Online these dangerous falsehoods spread at lightning speed."

Lear's enduring relevance

Although the bulk of Lear's work as a television writer and producer was done by the mid 1980s, the shows he created remain relevant even to the present day. In 2019, when Jimmy Kimmel created "Live in Front of a Studio Audience," a series of television specials in which contemporary celebrities recreate decades-old sitcom episodes word for word on exact-replica sets, he started by resurrecting Lear's work for a new generation.

"Norman rejected the notion that uncomfortable topics and flawed characters need to be sanitized for our protection," Kimmel told Salon. "If anything, his then-groundbreaking idea to depict real people and serious issues on television comedies feels even more groundbreaking now than it did in the seventies."

Part of the thrill of Kimmel's series comes from watching beloved actors like Will Ferrell, Tiffany Haddish, Ellie Kemper, and Sean Hayes tackle the televised high-wire act of live performance. What's genuinely astonishing, however, is how Lear's writing still speaks so clearly to America's current cultural divisions decades after it first appeared.

In part one of the series' first installment, Woody Harrelson and Marisa Tomei channel Archie and Edith Bunker in an "All in the Family" episode called "Henry's Farewell." The episode features an extended comedic argument about whether a woman or a Black candidate would have a more difficult time being elected President that feels exceptionally prescient, given that it was written almost five decades before Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton became candidates.

In part two, Jamie Foxx and Wanda Sykes bring George and Louise back to life for a new generation in the pilot episode of "The Jeffersons," "A Friend in Need." The storyline crackles with intersectional energy and class conflict as Louise Jefferson struggles with whether to hire a friend as a maid. Marla Gibbs, reprising her role as the woman they did hire, notes that not one, but two Black women own apartments in the same high-end highrise, then slams the door of the episode shut with an explosive final line: "How come we overcame," Gibbs' Florence Johnston asks, "and nobody told me?"

"Live in Front of a Studio Audience" retired a few months later in 2019, this time with another "All in the Family" episode ("The Draft Dodger," which featured guest appearances by Kevin Bacon and Jesse Eisenberg) and an episode of "Good Times" ("The Politicians") recreated by Andre Braugher, Viola Davis, and a similarly accomplished cast. Any in-depth look at Lear's body of work would undoubtedly uncover a great many more shows that would speak to a present-day audience.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

In 1972, in fact, the year before Roe v. Wade, Lear produced an episode of "Maude" in which the title character — unexpectedly pregnant at 47 years old – decides to get an abortion. Although abortions had been depicted on soap operas before then, Maude was the first primetime character to terminate a pregnancy (in a comedy no less), and the deftness with which "Maude's Dilemma" handled the subject matter met the delicate moment in America. Might that episode be next in line for the "Live in Front of a Studio Audience" treatment?

"Comedy on television helps us learn about and understand each other. The power of comedy and media is still here." – Norman Lear

"We'd love to explore it," Lear's writing partner Brent Miller told Salon, "but have yet to officially pitch it to our partners at ABC and Sony."

Given the Supreme Court's recent overturning of Roe, "Maude's Dilemma" would seem like an obvious choice.

"We need to understand each other at the present moment," Lear said, sharing his vision for contemporary entertainment. "Comedy on television helps us learn about and understand each other. The power of comedy and media is still here."

The power of Lear's work remains clear. He and his writing partner are currently working on a remake of Lear's 1970s series "Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman" with "Schitt's Creek" alum Emily Hampshire in the title role. Many, like both Kimmel and Reiner, continue to keep Lear's legacy alive in their comedy, too, making audiences laugh and think in an effort to change the world for the better.

"I'll always be grateful for Norman's wisdom and guidance," said Reiner.

On his 100th birthday, so should we all.