To say that Roger Angell was America’s best baseball writer feels insufficient. It is true—of course—but it misses so much.

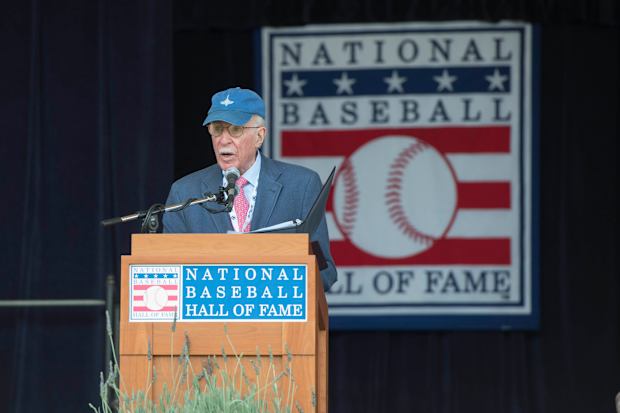

For more than half a century, Angell wrote about baseball for The New Yorker, covering not the sport itself so much as the experience of what it meant to care about it. He was a Hall of Famer who could not have been more deserving. Angell died at home in Manhattan on Friday from congestive heart failure, his wife told The New York Times. He was 101 years old.

Angell profiled generations of the biggest stars in the game. He wrote about every World Series for decades; he covered spring training and the minor leagues and entirely forgettable weekday contests. But what tied all of this work together was its sense of purpose: Angell understood just why people watched baseball and just why people wanted to read about it. He knew what made the game important alongside what made it anything but. And he understood all of this because he lived all of this: Roger Angell was a baseball fan. If this seems like it should be a given for a baseball writer, it hasn’t always been, and that’s illuminated by the gap between his work and that of so many others. Who else could write this experience of spring training from the stands (1962) and this incisive profile of Bob Gibson (1980) and this meditation on watching a blown save with his wife (2011)? The common thread is the understanding of what it means to love the game.

Gregory Fisher/USA TODAY Sports

Beyond this grasp of fandom, Angell was simply talented. His 1975 profile of Steve Blass, “Down the Drain,” is a master class in reporting that is sensitive while being direct. And that’s to say nothing of the quality of the sentences. (“Professional sports have a powerful hold on us because they display and glorify remarkable physical capacities, and because the artificial demands of games played for very high rewards produce vivid responses,” he wrote. “But sometimes, of course, what is happening on the field seems to speak to something deeper within us; we stop cheering and look on in uneasy silence, for the man out there is no longer just another great athlete, an idealized hero, but only man—only ourself. We are no longer at a game.”) The piece manages to get at an understanding both of how it felt to be Steve Blass and how it felt to watch him. Which is what Angell did best: He never stopped trying to understand.

My grandfather died when I was 14—old enough to treasure baseball as something that bonded us, a shared language and calendar, but still too young to have been curious about the exact contours of his interest in the sport. As a child, I knew the basics of who he rooted for. As an adult, I never had the chance to ask what he appreciated about the empty spaces in a game or learn what his own childhood baseball memories had been or notice his approach to keeping score. But years later, sifting through some of his books on a visit to my grandmother, I was thrilled to find a copy of Angell’s Five Seasons.

I was fresh out of college at the time; I had discovered Angell’s work only a few years previously. This was my favorite of his collections, and it held my favorite individual passage of his work, in an essay titled “Agincourt and After.” It is ostensibly about the 1975 World Series but more categorically about caring:

“What I do know is that this belonging and caring is what our games are all about; this is what we come for. It is foolish and childish, on the face of it, to affiliate ourselves with anything so insignificant and patently contrived and commercially exploitative as a professional sports team, and the amused superiority and icy scorn that the non-fan directs at the sports nut (I know this look—I know it by heart) is understandable and almost unanswerable. Almost. What is left out of this calculation, it seems to me, is the business of caring—caring deeply and passionately, really caring—which is a capacity or an emotion that has almost gone out of our lives. And so it seems possible that we have come to a time when it no longer matters so much what the caring is about, how frail or foolish is the object of that concern, as long as the feeling itself can be saved. Naïveté—the infantile and ignoble joy that sends a grown man or woman to dancing and shouting with joy in the middle of the night over the haphazardous flight of a distant ball—seems a small price to pay for such a gift.”

My grandfather’s copy of the book—just like mine—had this passage marked. The neat little fold in the corner of the page felt like an unthinkable gift; it was somehow far more specific, more intimate, more telling than if there had been a note with my name tucked inside. It did not answer all of the baseball questions I had lost the chance to ask him. But it answered just enough: To think of my grandfather reading the paragraph, feeling a spark of recognition, turning down the page to save it for later was enough.

Roger Angell knew what it meant to care about baseball. More than anyone who has written publicly about the game, he worked to understand that feeling in all its many dimensions, and to capture it on paper. A reader could not have asked for anything more. How lucky we all were to take it in, and to turn down the corners of the pages, saving them for later.