In her indictment, the prosecutor described Ilse Koch as “a sexy-looking depraved woman who beat prisoners, reported them for beatings, and trafficked human skin”.

Ilse’s husband, Karl Koch, had been commandant of Buchenwald, one of the first and largest concentration camps within Germany’s 1937 borders, from August 1937 to October 1941. He would then briefly serve as a commander of Majdanek, another notorious concentration camp.

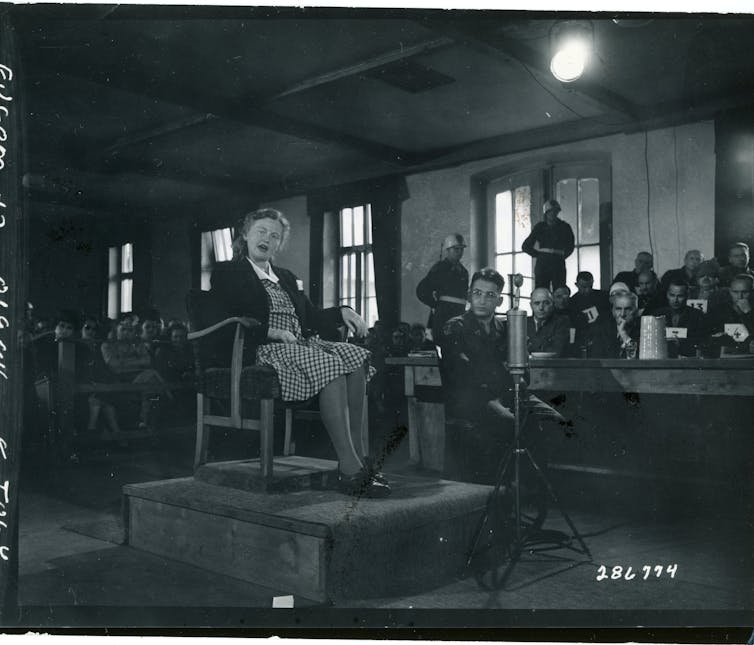

On 11 April 1947, two years to the day after American forces liberated the camp, the Buchenwald trials opened in a courtroom in the internment camp of Dachau, the site of the former Dachau concentration camp. The trials were run in the US-occupied zone, by American military tribunals.

The Kochs had initially been arrested in 1943 and tried before the SS military court. Charged with embezzlement and (in Karl’s case) the unauthorised murder of three prisoners, Karl Koch was convicted, and executed in 1945 for his crimes.

However, Ilse was set free due to the lack of evidence against her – and American forces later pursued her for her involvement with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Review: Ilse Koch on Trial: Making the Bitch of Buchenwald – Tomaz Jardim (Harvard University Press)

Prisoners referred to Koch as the “commandeuse”, suggesting a degree of authority as wife to her commandant husband. But Koch always claimed:

I was a housewife […] I have three children […] the operation of the camp didn’t concern me […] In [my husband’s] eyes, my primary job was to be the mother of our children.

The press referred to Ilse as the “Witch of Buchenwald”, the “Bitch of Buchenwald”, and the “Beast of Buchenwald”: a sadist and a pervert who was morally compromised, and a nymphomaniac.

Tomaz Jardim’s Ilse Koch on Trial argues the pervasive myth of Koch’s most sensationalised (yet unproven) crimes illustrates that the judgements of the public and the press were “as formative as the judgement of the courts in generating the enduring image of the ‘Bitch of Buchenwald’”.

Joined the Nazi party ‘early’

Koch was born in Dresden in 1906, to a middle-class family. Her mother was a housewife, her father a labourer.

She had an ordinary childhood. She left school early and started working full-time when she was 15. She joined the Nazi party earlier than most of her peers, in 1932.

At the time, the Nazi party appealed to young people because fascism seemed a viable solution to the deep economic recession that had followed the first world war, and had impoverished many German families.

The idea of an Aryan master race built on anti-Semitism also appealed to Koch, who saw herself as a true representative of such a race. Her future husband, Karl Koch, shared those sentiments.

The couple married after Koch collected evidence of her Aryan ancestry. She was expected to breed pure-race children and, with Karl, she gave a birth to three: two daughters and one boy, whom she raised with the help of maids and camp inmates.

Koch lived with her family in a three-story villa on the grounds of the Buchenwald concentration camp. More than 56,000 people died there from starvation, torture, illness and executions.

The executions of Buchenwald prisoners, writes Jardim, occurred in multiple forms: “shooting, hanging, gassing, corporal punishment, experiments withholding food and [the] refusal of medical care”.

Tried for awareness and participation

“It would have been easy for me to obtain false papers and live somewhere with a false name,” Ilse Koch wrote in 1946. “It also would have been easy for me to have disguised myself.”

But, she continued, “I had no reason whatsoever to disappear. I never even conceived of the possibility of being put to trial.”

The American prosecutor did not prosecute Koch and the other Buchenwald suspects for the “direct perpetration of war crimes”, but for “participating in a common design” to commit war crimes.

The officers who made up the military courts at Dachau were, writes Jardim, “honest and competent men”, but they were not lawyers or professional jurists.

Dressed up and with her head held high, Margarete Ilse Koch entered the courtroom. She was the only woman among 31 indicted for the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Buchenwald.

The legal doctrine of “common purpose”, which addresses complicity in a crime or crimes, was a useful tool for prosecution in World War II cases like Koch’s. (It has since been further developed by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, under the different name of “joint criminal enterprise”.)

The relevant legal provision stated that any person was deemed to have committed a crime if “he was connected with plans or enterprises involving its commission” or was “a member of any organization or group connected with the commission of any such crime”.

So Koch was to stand trial not because she had status within the Nazi system or had killed someone herself, but because she knew of the coordinated criminal enterprise that was the Buchenwald concentration camp. And she was tried for her alleged awareness of the camp’s nature, and her voluntary and active participation in its enforcement.

Combining “sexualised imagery, gender stereotypes, and sadistic or fetishised violence”, writes Jardim, these reports created a thirst for details of her trial, with the public eagerly awaiting a guilty verdict. Her image was “monstrous and sexualised”.

‘A creature from some other tortured world’

Koch lived a luxurious life, built on her husband’s illegal activities, which were illegal even in the context of Nazi Germany. Ironically, the executions of 50,000 people at Buchenwald were “not wrongful according to the National Socialist system”.

The concentration camps became more than just death factories. They became centres where food and other valuable items could find their way onto the black market. Jardim writes that they were places of “deep corruption, grift, and embezzlement”, where Koch and his cronies pursued “an illicit trade in luxury goods produced by prisoners”.

Karl Koch was executed for placing himself “beyond the order of the concentration camp” and its prohibitions against illicit trade and embezzlement by Nazi officers, as well as the three unauthorised murders.

In the 1947 trials, American prosecutor Denson described Koch as “no woman in the usual sense but a creature from some other tortured world”, making her a powerful symbolic representation of Nazi crimes.

Witnesses claimed “she wore clothes which were deliberately chosen to be inciting for the prisoners”, writes Jardim, citing trial transcripts. They accused her of whipping prisoners for daring to look at her and of having “a desire to own certain objects made of human skin”, such as lampshades, a cover for a family photo album, and gloves.

Various objects made from human skin were found in Buchenwald when it was liberated, but no connection to Koch could be proven. Other allegations against Koch were also found to be “spurious” by judicial authorities.

Nevertheless, writes Jardim, the media exacerbated these allegations, which, once believed, fuelled hatred against the “bestial” Koch. Although the allegations against her were based on “a considerable degree of hearsay and conjecture”, her credibility was so undermined that no one could believe she “knew nothing” about the concentration camp and the treatment of its inmates.

On 14 August 1947, Koch was sentenced to life imprisonment by the US military court. At the time, she was seven months pregnant with her fourth child, Uwe, whom she conceived with an unknown father in her prison cell in Dachau. This further fuelled popular stories of her “flawed motherhood and moral character”.

A few months later, following various legal twists and turns, her request for clemency succeeded. The court concluded that there was no overwhelming or substantial evidence against Koch and commuted her sentence to four years imprisonment.

‘Diabolical’

The announcement sparked public outrage. The popular perception of the Koch case and the “diabolical image” painted by the press stood in striking contrast to “the reality that emerged from the evidentiary record and led to the commutation of her life sentence”, writes Jardim. Mounting criticisms of the court’s finding of clemency erupted into public protests.

Despite the uproar, her commutation remained in place and she was released in 1950. However, in the same year as her release, she was charged again – this time by the Western German authorities.

While Jardim cites original data from the trial, there is still some confusion about the exact numbers attached to Koch’s charges. One 2021 article (which acknowledges this inconsistency) summarises them as: instigating the murder of 45 prisoners, complicity in 135 other murders, and one attempted murder.

In 1951, Koch was sentenced to life imprisonment once again. This time, she remained in jail until her death by suicide: she hanged herself with a bed sheet in Aichach Women’s Prison on 1 September 1967.

Women and war crimes

The role of women perpetrators in the Holocaust and beyond remains a growing yet under-researched topic. Studies on Ilse Koch have possibly been more common than those on other women war criminals, because the media sensationalised her story.

Ilse Koch on Trial reminds us that women, too, are capable of committing war crimes. It also reminds us that “such women” – who fail to conform to feminine expectations and gendered stereotypes – risk becoming cast as monsters in ways men are not. While it’s normalised that men can kill, especially in war, women are still stereotyped as peaceful and nurturing – which is reflected in the gendered reactions to women war criminals.

In more recent history, Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, a woman convicted of genocide in Rwanda, was called an “evil woman” and “the mother of atrocity”. Similarly, Biljana Plavšić, who was convicted of crimes against humanity in Bosnia and Herzegovina, was described as a “monster” in a female form.

Jardim writes that in preparation for Koch’s third and final trial, her violation of gender norms was treated as “central to her guilt and a key factor in determining her punishment”. It was stated that “[b]eing a woman made her participation more unnatural and more deliberate”. Her psychiatric assessment revealed “a level of cruelty alien to female nature”.

While no one denies Ilse Koch was guilty of terrible crimes, the most sensational atrocities attributed to her remain unproven. Jardim argues the widespread condemnation of Koch diverted attention from the more consequential – but less sensational – complicity in the Third Reich’s crimes, not only of high-profile Nazis, but millions of ordinary Germans who “supported, enabled, and carried out Nazi policies”.

Gendered perceptions of violence and culpability drove an eager support for prosecution of Koch, at a time when thousands of male Nazi perpetrators who were responsible for more significant crimes escaped punishment or received lighter sentences.

The “popular fascination with [Koch’s] sadistic violence and sexual domination” continues to thrive in popular culture, Jardim writes. It provides “an easy target of popular condemnation for a generation of Germans eager to distance themselves from the Nazi period”, and from “the broad complicity that brought the Third Reich to power”.

Olivera Simic does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.