You can imagine the scene.

Or perhaps you’re already living this particular slice of modern Americana: A family crams into an SUV and barrels down the interstate, parents in front, a preteen athlete buckled up in back. Collectively, they’re committing dozens of weekends, hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars toward a shared athletic pursuit.

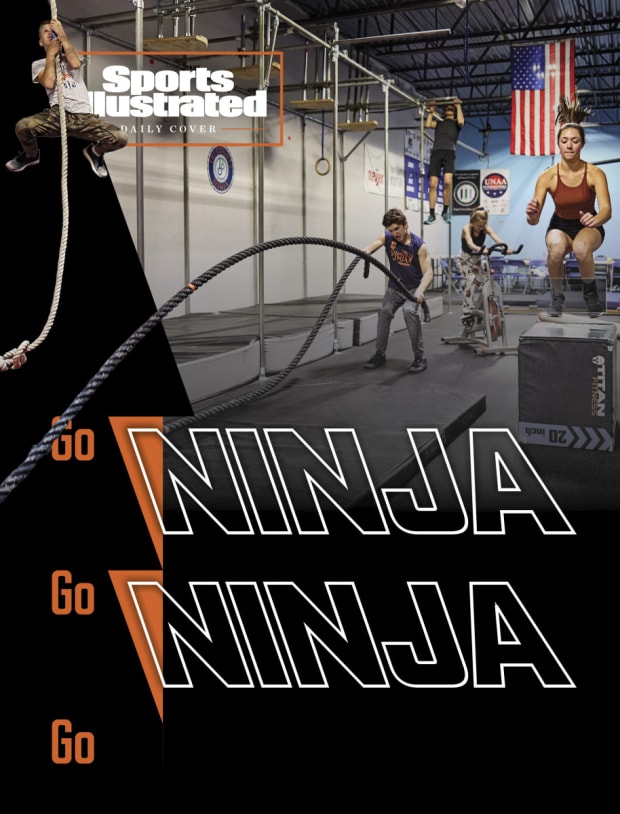

In this instance, though, no basketballs roll around in the trunk, no metal bats clang as the car rumbles down the highway. The DuBrys of Fenton, Mich.—Shawn, 49; Belinda, 48; and their 11-year-old son, Landen—have piled into a white Ford Explorer seemingly every weekend since 2021 and pointed not toward hardwood courts or white-chalked fields but toward, typically, some refurbished warehouse brimming with metal and wooden structures upon which Landen will test his formidable ninja skills against the nation’s best.

Say again? Ninja?

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

What, exactly, are Landen and his fellow ninjas chasing? A spot on a reality TV show in which only one contestant, emerging from tens of thousands of applicants, earns a paycheck. A scholarship, hopefully, in a sport that doesn’t yet exist on the college level. A chance to someday make an Olympic team, if organized ninja can survive a near-decade-long bureaucratic obstacle course.

Right now, though, a happy son will suffice. Says Belinda: “He’s at peace.”

For as long as Landen’s parents can remember, he has dealt with severe anxiety. An approaching thunderstorm could rattle him. He fretted all night before school field trips. At age 6, though, he started spending an hour each week watching the NBC reality competition show American Ninja Warrior, and he became enthralled by the athletes darting, dangling and diving their way through intricate obstacles—so Shawn and Belinda took Landen to a ninja gym. And there their worries were quieted as he learned to navigate courses, like the ones on TV, with increasing guile and ever-improving grip strength, to the point that they started drawing concerned looks at the local playground as their spindly blond boy hopped and soared around as if gravity’s tug were merely a suggestion.

Five years later, the shelves of Landen’s bedroom are peppered with six-inch-high trophies. On one wall, the lanyards of a dozen-plus medals blend into a rainbow of fabric. And on the door, a pull-up bar is affixed to the frame above a small mattress he slides into place to cushion any falls.

Depending on which list you consult (and quite a few exist), Landen ranks somewhere among the five best U.S. ninjas in his age group. He can fling himself as far as 12 feet, from bar to bar or obstacle to obstacle—a lache in ninja parlance—a metric as important to him as shooting percentage or batting average.

“If you take the people who’ve been on the show [as a percentage of] the ninjas that are out there competing, it’s nothing—it’s minuscule,” says Belinda. “There’s an entire community of ninjas that are not on the show.”

Landen is one of tens of thousands of athletes estimated to be competing globally. Yet, ninja gyms aren’t filled with type-A professionals looking to blow off steam after work, as is often the case in running clubs, CrossFit gyms or Tough Mudder

events. Instead the sport is more like gymnastics; parents and gym owners estimate that roughly three-quarters of ninja athletes compete in youth divisions, many of whom, like Landen, were entranced by the show.

Though ninja seems to appeal mainly to kids and teens, it hasn’t proved immune to the sort of grown-up problems that plague major sports: Already ninja has been rocked by a scandal involving its biggest star. A handful of ninja leagues are jockeying forcefully for power and market share. And ninja squabbles churn on social media, largely over who’s best equipped to steer the sport on the world’s stage.

As all of this swirls, the DuBrys—and plenty of families like them, with kids who feel they don’t fit in anywhere other than a ninja gym—continue to crisscross the country, showing up at cold warehouses and forlorn strip malls as their children catapult themselves through the air, arms outstretched, hoping to find something firm to grab hold of.

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

American Ninja Warrior’s television forebear debuted on the Tokyo Broadcasting System in 1997 under the name Sasuke (named after a monkey-like ninja in Japanese folklore). In every episode, 100 competitors battled against one another—and a four-stage course. In 40 competitions, only four ninjas have ever conquered all four stages and emerged victorious. By 2006, a dubbed version of the show found its way to the U.S. on the cable network G4, and in ’09, an English-language spin-off was launched on the network, proving so popular that NBC picked it up.

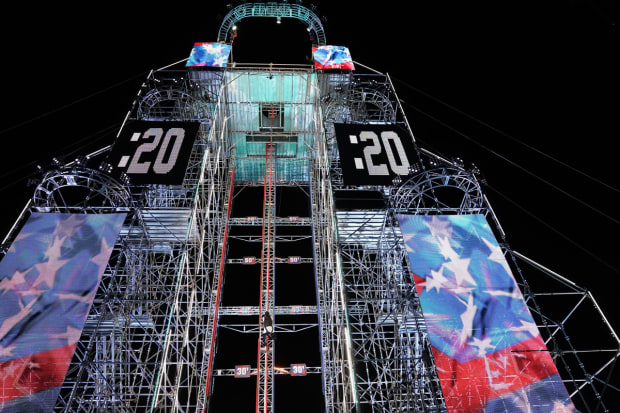

A decade later, offspring of Sasuke are recorded in 20 countries and broadcast in 160. In the U.S., $1 million is rewarded to the ninja who most quickly completes the imposing final obstacle, Mount Midoriyama, a replica of Sasuke’s plopped down on the Las Vegas strip. Only three U.S. ninjas have reached the top (though just two collected the grand prize—two competed in the same season, leaving one as runner-up). When Midoriyama isn’t conquered, $100,000 is awarded to the “last ninja standing” in the year’s final event—essentially, the competitor who advances farthest.

The show’s U.S. popularity peaked in 2015, when, on average, more than 6.5 million people tuned in for each episode. (Today, viewership hovers around half that figure.) Along the way, a slew of celebrity athletes have competed, including the NFL’s Chris Kluwe and Shawne Merriman, the WNBA’s Tamika Catchings and Olympic gymnast Jonathan Horton. NBC will premiere the show’s 15th season on Monday.

In parallel with American Ninja Warrior’s success, a grassroots sport started to flourish. At first, fans crafted their own home courses. Then basements and backyards gave way to converted warehouse gyms, filled with ragged, unsightly DIY obstacles. From those gyms sprung local and regional leagues, a few of which even turned national. Nearly 400 ninja gyms have sprung up across the U.S., according to the website Ninja Guide, with hotbeds in the Northeast, Florida, California and Texas.

Kaden Lebsack’s path to a ninja gym is not atypical. Years ago, he started watching American Ninja Warrior with his parents each week on TV and thought the obstacle course looked “like a big playground.” To scratch that itch, his mom, Brandi, put him in parkour classes. But “it just wasn’t the same,” she says. So when Kaden was 10 the Lebsacks enrolled him in classes at a ninja gym 90 minutes from their home in Castle Rock, Colo.

Eventually, that daily round trip soon grew too onerous—but by then Kaden had already demonstrated true talent: Just two months in, he finished third in his age group at a championship event in Albuquerque. So the Lebsacks opened their own gym, Ninja Intensity, committing in full to their child’s dream by renting a warehouse and filling it with obstacles and training equipment.

A half decade later, that commitment was rewarded in a way that most Little League parents can only imagine. In 2021, Kaden, at age 15—the youngest at which contestants are eligible—was named the last ninja standing on the U.S. show, not quite beating the clock on the 75-foot rope climb that marks the 23rd and final obstacle. For a teen to win is rare, but Kaden did it again one year later, successfully defending his title in the show’s 14th (and most recent) season, though he was once again unable to beat the 30-second clock on the rope climb. For each triumph he won $100,000—a small windfall that he’s used, in part, to self-fund his own local competition and launch a hand chalk company.

But it’s all had a cost. Now 17, Kaden trains six days a week, mixing weightlifting, parkour and obstacle work. He regularly receives massage therapy and is seemingly on the road for as many weekends as he’s home. He’s old enough now to travel alone, and he often stays with other ninja families rather than at hotels, important since the Lesbacks devote thousands each year toward this pursuit.

Brandi describes her son as an introvert who had little affinity—or talent—for team sports. In ninja, he’s found not only notoriety but a home. Says Kaden: “I don’t really have any friends that don’t do ninja.”

Lindsay Kappius

The successes of Kaden Lebsack are never far from mind among the crew of adolescents, tweens and teens (Landen DuBry included) who show up nearly every day at Tri County Ninja in Fenton, which adjoins a Sears, its storefront filled with lawn equipment.

Inside the repurposed warehouse, human superballs fling themselves from unwieldy plastic rings and bars suspended from steel scaffolding, while others scurry up the trio of towering, curved (better known as “warped”) walls looming in the corner, the tallest of which stands a foreboding 14' 8". On the rear wall, there is a peg board, navigated by ninjas who insert and hang from wooden rods along a jagged course of holes. And beside that hangs a homemade wooden salmon ladder, which a ninja ascends by dangling from a horizontal metal pole and heaving it up a series of vertical grooves.

The kids, many of whom aren’t quick to make eye contact with strangers and are prone to slumped shoulders, seem to double in size in that room. They laugh and—quite literally—bounce off the walls.

The gym is the brainchild of Ed and Megan McNulty. Ed, 39, who operates a table game shop (think Magic: The Gathering) in the front of the gym, was hooked by the show when it aired on G4 and soon began training on homemade obstacles in

his basement. He was still working as a police officer when he and Megan leased the empty space adjoined to the Sears in 2018, and Tri County opened its doors. No longer on the force, McNulty frequents local steel mills and leans on friends with professional-grade woodworking equipment to help fabricate the obstacles. Anything that’s not plastic in his gym came from elbow grease and handy acquaintances. “This place doesn’t scream safety,” McNulty says, laughing as he surveys the clutter. There isn’t a body that certifies ninja gyms’ safety, but McNulty notes that with all the crash pads around, injuries among his young athletes are surprisingly uncommon.

COVID-19 took a toll on his gym and the state: McNulty’s competition team dwindled from 33 members to only 10, who are charged $150 a month for access to the gym and contests. Tri County’s membership fees are much lower than the norm; the McNultys now fund the operation largely by throwing birthday parties—they scheduled 18 in this past March alone. (And, yes, attendees’ first order of business is signing a lengthy safety waiver.) Rather than robust profits, McNulty cares more about providing a refuge for kids who tend not to be included on basketball and homecoming courts alike. “They’re not the star athlete,” he says. “They’re just, you know, maybe a little different. Maybe a little quirky.”

Training alongside DuBry and the others is 17-year-old Nolan Diesch. He and his father built a custom training rig in their garage and, for ninja, the family has visited Las Vegas, the Carolinas, Florida, Chicago and Buffalo. Above all else, he yearns to be on American Ninja Warrior and experience the highs Lebsack has. He’s capable, currently ranked in the top 50 among men of all ages by the Ninja Sport Network—one of many national ninja competitions—but it’s a reality show and not a sport. Performing well in regional and national competitions doesn’t guarantee an appearance. It’s only half of the equation.

The application requires not performance metrics but videos demonstrating a boisterous personality, a unique trait or a moving backstory. Factors that appeal to producers and mass audiences are not common among some of the sport’s many introverted competitors like Nolan. Some parents have even gone as far as to get their children media training—which typically costs in the low four figures. Universally, the Tri County parents say it’s wrenching to have to explain to their confused children that missing a spot on the show has nothing to do with their athletic prowess. “So, that’s what we’re working on right now—it’s just to get a video together,” says Nolan’s mother, Melissa. “His ultimate goal is to be on the show.”

which has been conquered just three times.

Elizabeth Morris/NBC

Landen DuBry’s biggest achievement in his young career came when he placed third at last year’s World Ninja League championships. Among the alphabet soup of regional and national ninja leagues in the U.S., three, arguably, stand above the rest: the WNL, the Federation of International Ninja Athletics (FINA) and the Ultimate Ninja Athlete Association (UNAA). Each has slightly different rules: At WNL competitions, fall on an obstacle and your competition is finished, just like the show; for FINA and UNAA, you’re docked points for falling but still get to tackle the course in full. “If you ask 100 people what the premier thing was, you’d probably get [a ton of different answers],” McNulty says.

Like McNulty, WNL founder and president Chris Wilczewski grew enthralled with the show in its early years on G4 and, with his brother, Brian, soon started cobbling together obstacles in their parents’ New Jersey backyard. Eventually, the custom-built rigs attracted so many local athletes that the brothers opened a gym of their own—and earned them both slots on American Ninja Warrior. Chris appeared in nine seasons and Brian in four (competitors are eligible to apply every year). “We kind of outgrew my parents’ backyard,” he says now, laughing. “I think they wanted their space back.”

Opening a gym, naturally, led to hosting local competitions. As those started to fill up, Wilczewski tapped other ninja gym owners in the Northeast to begin hosting competitions under the WNL banner with consistent rules at each event, laying the foundations for what eventually grew into a national endeavor. Now, the World Ninja League has hundreds of events each year, featuring more than 30,000 athletes—competing across age brackets, from children to seniors—that culminate in an annual world championship. The challenges of shifting from backyard to business were manifold: working with equipment manufacturers, negotiating lease agreements with facilities, ironing out insurance policies, implementing consistent safety standards and finding trustworthy partners across the country. “A lot of our time and energy has been spent and focused on: How do you make ninja very accessible for a mainstream audience?” Wilczewski says.

The leagues all aspire, even without saying it directly, to claim the biggest piece of the pie. They sometimes scrap about safety standards and which judges are sufficiently qualified to preside over competitions. “Ultimately, I think having multiple organizations working towards the same goal is never necessarily a bad thing,” Wilczewski says. “That competition is driving the sport forward.”

Some in the ninja community, though, disagree. George O’Dell, who manages Train Yard 317, a gym in Indianapolis, and temporarily galvanized the sport under a national governing body, worries that divisions between leagues could lead to a flawed system with uneven standards that might endanger the sport or its athletes. “I think we’re very much in our infancy,” he says. “So that’s super damaging to create any divide right now.”

Given that so many ninja competitors are children and teens, ensuring not only their physical safety, but safety from potential predators in such an unregulated landscape has proved vital. That need came to the fore after the sport’s most recognizable figure—Drew Drechsel, who was the last ninja standing on the show in 2016 and ’18 and conquered Mount Midoriyama in ’19—was arrested in August ’20. Federal prosecutors charged him with an array of sex crimes, including the manufacture of child pornography and enticement of a minor to travel for illicit sexual conduct, tied to his interactions with a teenage female fan. The teen said in a ’20 criminal complaint that, in ’15, when she was 15 and he was 26, he engaged in intercourse and oral contact on her behind the warped wall in his Connecticut ninja gym, and she said the two traded illicit messages in the following years.

American Ninja Warrior’s most decorated athlete, Drechsel was cut from already-taped episodes shot for the 2020 season. He remains in custody and is awaiting trial, facing up to 30 years in prison. His attorney has said he will plead not guilty. Drechsel had once been vital to the WNL’s promotional efforts, but the league distanced itself from him after his arrest.

The incident spurred ninja gyms and leagues across the country to more closely interrogate which judges and coaches they permit around young athletes, as concerned parents fretted about the risks their own children may face during long hours on road trips or at practice. “I’m sure that the community lost members because of the unfortunate actions of a single individual,” Wilczewski says, “which I think is depressing, disappointing.”

Elizabeth Morris/NBC

Inherently, fads are fleeting, and reality shows have proved no exception. American Ninja Warrior’s audience has been halved in recent years, akin to comparable drops in most network programming, live sports included. “It is a reality show,” says O’Dell. “At the end of the day, it does have a shelf life.”

So, whenever the show signs off for the final time, what might it leave behind? Can the domestic leagues—driven largely by the show’s popularity—endure? Considerable interest exists within the community to aim even higher by bringing ninja to the Olympics, which would give the sport a prominent new TV platform and would afford young athletes a new goal for which to strive: one that can be reached based on merit, not marketability.

Already, significant progress has been made. Last November modern pentathlon’s governing body approved obstacle racing—in this case, ninja under another name—as one of the sport’s five disciplines, replacing equestrian. The new event will debut at the 2028 Summer Games in Los Angeles, pending approval from the International Olympic Committee.

The push to make ninja a full-fledged Olympic event is being led by World Obstacle—the international governing body for ninja, obstacle course racing (often basic-training style Tough Mudder events) and adventure racing (racing through the wilderness on bikes, kayaks and more)—and its president, Ian Adamson, a former adventure racing star. Over the past year, the group has hosted a series of ninja exhibitions around the world, with stops in Poland, Italy and the Philippines.

The idea of ninja becoming a medal sport isn’t as far-fetched as it might seem. Adamson hopes to take advantage of the IOC’s push to modernize the Games—skateboarding and sport climbing, for instance, debuted in Tokyo. World Obstacle

has already helped establish more than 115 national ninja and obstacle federations: While the U.S.—governed by the USA Ninja Association, a successor to the hastily formed NinjaUSA group helmed by O’Dell—is the global hotbed, the sport is increasingly popular in places like the Philippines, the United Kingdom, Italy and, of course, Japan. To appeal to the IOC’s desire to woo a younger audience, World Obstacle, in agreement with the Tokyo Broadcasting System, is testing a 50- to 100-meter ninja course with eight to 12 obstacles that will largely mimic what viewers have grown accustomed to watching on American Ninja Warrior. A broadcast advisory group told Adamson that it should look like the TV show. “Which I 100% agree with,” he says.

Pushing ninja to the Olympic level will require quite a bit more than producing a snazzy TV product: distributing rules and regulations to national governing bodies; dealing with groups like WADA and USADA to drug-test athletes; and establishing safety standards and protocols are all paramount. “We are getting stronger and bigger,” says Michel Cutait, World Obstacle’s acting secretary general. “What we are doing is having very clear rules, spreading the rules to everyone, and making sure that everyone has the capability to apply the rules.”

Grand plans like those, which sound good on paper, are prone to immolation when they’re exposed to outside elements. Last October, World Obstacle, in conjunction with NinjaUSA, attempted to put on a “World Cup” event in Indianapolis that would double as a preview for an Olympic-style course. The event would present a chance for athletes who compete in an array of leagues to gather under one umbrella, with the top finishers named to an honorary “national team.” Hotels were booked. A massive venue north of the city reserved. Travel plans made. Entry fees paid. Expectations among little ninjas and their parents soared. McNulty even constructed a replica of the World Cup course at his Tri County warehouse.

Then, only a week before the event, parents began receiving email notifications that their hotel rooms had been canceled. Group text chats were soon littered with confusion: Was the event canceled, too? Who was responsible? Why hadn’t we been told? Families had to scrap longstanding travel plans—many built vacations around the Indy trip—unaware, until the 11th hour, that O’Dell and the event coordinators had issues managing the logistics inherent in hosting an event of that scope. (O’Dell did not respond to questions about the event.)

“I think it disappointed so many people,” says Brandi Lebsack, mother of Kaden. “My heart breaks for the kiddos who were thinking, Oh my gosh, this could be my Olympic chance, my Olympic dream.”

With O’Dell’s NinjaUSA group now defunct, the event has been tentatively rescheduled for this summer under the auspices of the new USA Ninja Association. All of the change and turmoil has left parents uncertain about the sport’s Olympic future. “I’m hoping they have the right group of people now . . . that can make it legit, can make it an Olympic sport,” Brandi says. “I don’t want the sport to die once the show does.”

Parents like Lebsack and DuBry worry about the homogenization that this Olympic movement might bring. Athletes and families alike say they love ninja because each gym and each competition provide a unique test. It isn’t played on a 100-yard field or defined by 90-foot base paths: No two courses—or sets of rules—are the same. More stability and notoriety, they fear, may cost the sport its improvisational soul.

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

Spartan Ninja Warrior occupies a small corner of an East Lansing, Mich., dance and fitness studio that itself takes up half of an abandoned grocery store. Old fluorescent lights and sprinkler heads still hang precariously from steel rafters above, the ceiling tiles long since removed. It’s the personal playground of Tristin Martin, 10, among the nation’s best ninjas in her age group. Her parents, Nichole and Scott, helped build and assumed management of the small space only three miles from their house after growing weary of shuttling Tristin 45 minutes and back to the nearest ninja gym each day.

The Martins poured themselves into the sport because, when Tristin was 5, she was prone to wedging her hands and feet against the walls of a narrow walkway at their home and scurrying forward without touching the ground. They’d catch her climbing up the trim of their bathroom door or the joists and bolts in their basement, and hanging upside down while reading, legs locked in rings suspended from the ceiling above. Tristin had never quite blended in with her peers: She favors her hair spiked and dyed in vibrant colors, and dyslexia made school her most challenging obstacle of all. But the letters seemed to align when the world inverted. “The next place for her to jump was out our bathroom window [and then] off of our roof,” Nichole says. “Like, we’ve got to find an outlet.”

By February 2020, Tristin’s at-home acrobatics led her all the way to WNL’s World Championships in Greensboro, N.C., where she earned second place in her age group. The Martins realized they had little choice but to cultivate what she loved and what seemed to focus her boundless energy, which yielded dramatic improvements in school. So, the family has committed to the life that the DuBrys and so many others have, bouncing every weekend among the likes of Columbus, Buffalo, Chicago and Pittsburgh—the Martins put 20,000 miles on a new GMC SUV in five months’ time—and spending dozens of hours a week shuttling their daughter among ninja, parkour and agility classes, efforts that cumulatively cost the family around $20,000 per year.

An event this summer in Orlando will double as the family’s annual vacation. To help afford a ninja’s lifestyle, they’ll drive instead of fly. Scott cobbles together training equipment and obstacles from detritus he finds on the side of the road or by scouring Facebook Marketplace when they reach a new city for a competition. “I think the biggest hurdle to overcome is access to it and the financial costs that come with it,” Nichole says.

Tristin fell and broke growth plates in her elbow and wrist last year, but the injuries—ninjuries, she calls them—haven’t dissuaded her from taking bigger risks, bigger leaps, all in pursuit of—what? The family isn’t quite sure. They know a few older ninjas have translated their unique skills into pole vaulting and, in turn, college scholarships. Ask Tristin what she wants to be when she grows up and, depending on the day, it could be a firefighter or a police officer or an

American Ninja Warrior.

So, for now, a sinewy little girl with spiky blue hair and thick calluses on her hands will continue contentedly swinging from peg to peg and zooming between obstacles in an old grocery store, free of thought or worry as adults across the country—and the globe—sort out what her future might hold. All the while, her family will continue piling into their SUV for long weekend drives to chilly warehouses filled with children who seemingly find contentment only in the open air between metal bars and plastic holds. “We’ve always said that we wouldn’t push our kids into the things that we want them to be in,” Nichole says. “We’re not trying to vicariously live through our kids, but our kids will do something. And this is her something.”