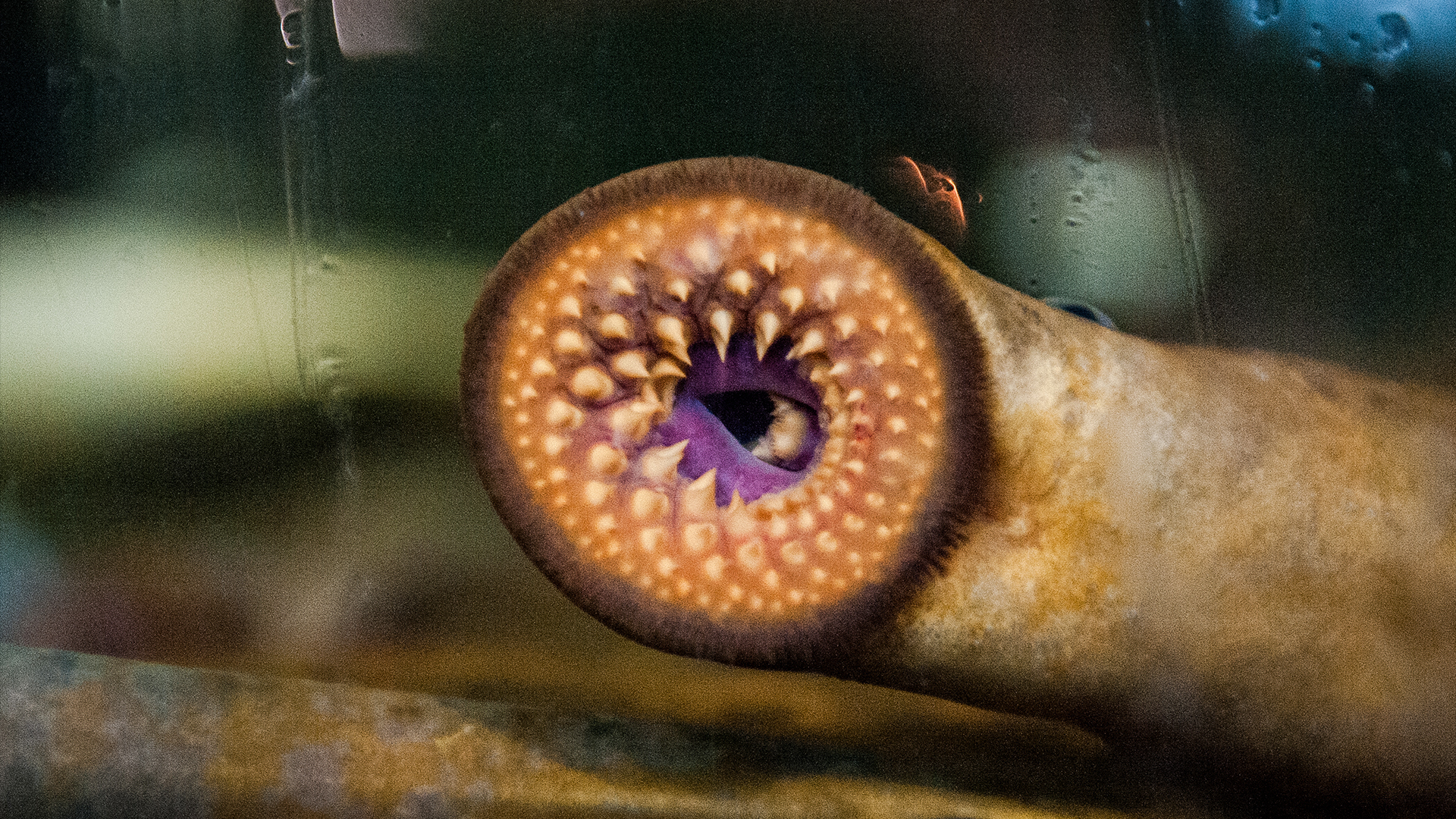

Lampreys are the stuff of nightmares, complete with long, slimy bodies; circular mouths filled with teeth; and parasitic tendencies. But lampreys are also vertebrates, which means they have backbones and share a common ancestor with humans — and new research is revealing that we have more in common with these slippery bloodsuckers than scientists previously thought.

Lampreys belong to an ancient vertebrate lineage known as Agnatha, or jawless fish. Previous research suggests that lampreys and their relatives represent the most primitive group of vertebrates still in existence, having evolved an estimated 360 million years ago. These living fossils can give us a window into how some of our distant ancestors likely evolved.

For the last 150 years, scientists assumed that lampreys lacked a jaw because they were missing a structure known as the neural crest. This group of stem cells is unique to vertebrates, and in the womb or the egg, it develops into a wide array of structures. These structures include both jaws and the sympathetic nervous system, which controls our involuntary fight-or-flight response that kicks on in dangerous or stressful situations.

But a new study, published Wednesday (April 17) in the journal Nature, reveals that lampreys have sympathetic nerve cells after all — suggesting that the vertebrate flight-or-flight response is more ancient than scientists expected.

Related: Can you 'catch' stress from other people?

"Studies like this help teach us how we were built over evolutionary time," Jeramiah Smith, a computational biologist at the University of Kentucky who was not involved in the research, told Live Science.

The new study did not begin as a search for sympathetic nerve cells.

"One of the things I love about science is that you often make discoveries by accident," Marianne Bronner, a developmental biologist at Caltech and co-author of the study, told Live Science. Instead, the work started as a search for similar cells that were precursors to the more complex neural crest seen in jawed vertebrates. They thought they might find such cells in lampreys because they are the closest thing we have to ancient jawless vertebrates that first emerged around 500 million years ago.

But when the researchers started dissecting lamprey larvae, they noticed the immature fish had structures that looked a lot like neurons running in a chain down the length of their bodies. This string of nerve cells is characteristic of a sympathetic nervous system — a system lampreys weren't supposed to have.

When the scientists looked closer, they confirmed that these structures were indeed nerves using RNA sequencing; RNA is a cousin of DNA that helps cells make proteins, in addition to serving other functions. The team also found that the cells make a precursor enzyme for noradrenaline, a key chemical messenger that helps control the fight-or-flight response.

"Now it looks like the only thing that lampreys don't have is a jaw," Bronner said.

Lampreys were previously assumed to react to danger by relying solely on pheromones given off by other lampreys. (Ecologists still sometimes use these pheromones to control the critters' movements in the lab.) The discovery that these jawless fish have a fight-or-flight response places the evolutionary origin of this system about 50 million years earlier than scientists expected.

Bronner thinks that past researchers probably missed the sympathetic nerve cells in lampreys for a couple reasons. One is that the fish have a long developmental cycle; after a young lamprey hatches, it can spend years developing in a larval stage before maturing into an adult. The sympathetic neurons may be too small to notice until late in this developmental phase, and most prior research was done on newly hatched lampreys. The new work uncovered the cells in older larvae.

Another issue is that jawless fish are far less studied in evolutionary biology than "model organisms" like fruit flies and zebrafish, which serve as a model for biological systems also found in humans. Such species are great for lab work, especially as scientists know their genomes so well. But Bronner sees huge scientific benefits in studying creatures like lampreys, too.

"Sometimes you have to go outside of your comfort zone and work on these weird animals," Bronner said — nightmare fuel and all. So the next time your adrenaline spikes when you're watching a horror movie or you've heard a twig snap in the woods, consider thanking a lamprey.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!