A Newcastle professor who pioneered a program that uses the military to prevent maternal deaths in Nepal says its success could be applied globally.

Laureate Professor Roger Smith's new research paper on the issue, published at the weekend, showed military helicopters were key to saving mother's lives.

"There is good evidence that the helicopter program has reduced maternal mortality in Nepal by about 40 per cent," Professor Smith said.

As of June last year, the service had "successfully retrieved 625 women in four and half years".

Nepalese census data showed a fall in the maternal mortality ratio from 239 per 100,000 births to 151 per 100,000 births from 2016 to 2021.

In comparison, Australia's maternal mortality ratio was about eight per 100,000 births.

"The efficiency of the [Nepalese] triage service continues to improve, suggesting maternal mortality will continue to fall," Professor Smith said.

"This is a model that could be applied in other low- and middle-income countries."

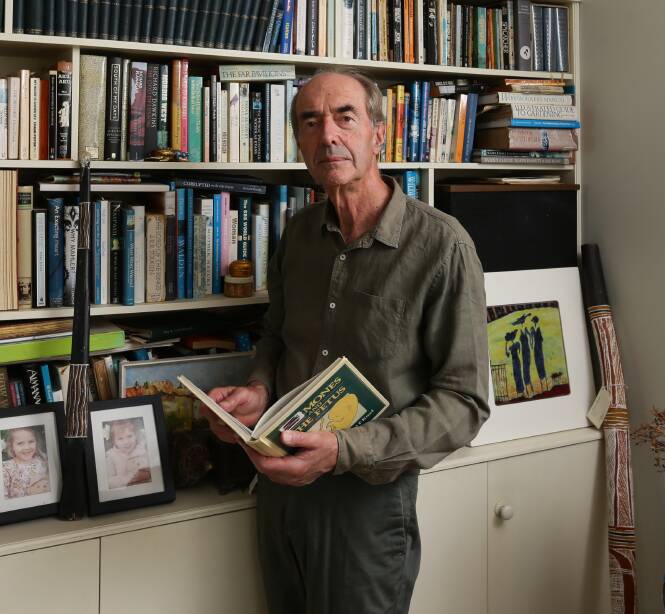

Professor Smith, who heads the Hunter Medical Research Institute's mothers and babies research program, is a world leader in premature birth.

He has published more than 400 research papers in journals.

He said the Nepal study - published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology - was "the most important paper I've ever been associated with".

Dr Binod Sharma, who gained a PhD in public health from the University of Newcastle, was also involved in starting the helicopter program in Nepal.

He said in a documentary that it became clear during his time studying in Newcastle that delays in transporting women to hospital had to be addressed.

Discussions about starting the helicopter retrieval program were held at Nepal's Ministry of Health in 2016-17.

About 94 percent of maternal deaths worldwide occur in low- and middle-income countries.

They refer to women dying while pregnant, or within 42 days of being pregnant, from any cause related to the pregnancy or its management.

The UN aims to reduce these deaths by two thirds to less than 70 per 100,000 births by 2030.

Nepal's use of military helicopters had "overcome the tyranny of poor roads" to rescue women in childbirth emergencies.

This enabled rapid transport of affected women to "a small number of fully-equipped and staffed hospitals".

As well as saving women's lives, the emergency retrievals helped pilots with the "ongoing training" they require.

Professor Smith believes other countries could follow Nepal's lead in using military helicopters for this purpose.

Doing so, would "not require an expensive investment".

Births in these poorer countries often occur without birthing experts.

They were often places where women "frequently have low standing", while cultural beliefs led to delays in recognising childbirth emergencies.

And pregnant women's families and carers may not realise their lives are in danger.

Further problems were a lack of transport to hospitals equipped to treat affected women and slow treatment on arrival at hospital.

"These delays operate like links in a chain. Failure of any of the links leads to death of the woman," Professor Smith said.

The paper said these countries had "characteristics that make it likely that the chain will break".

The paper highlighted that a "singing program" in Nepal had helped rural villagers understand the need for birthing experts.

"Singing is a traditional method for the transmission of knowledge in Nepal."