For decades, astronomers wondered if planets with twin suns like Luke Skywalker's fictional home world of Tatooine were only science fiction. Now, scientists have now discovered a new Tatooine-like system that is home to multiple worlds.

Binary stars, or two stars orbiting each other, are very common — about half of the sun-like stars in the Milky Way galaxy are in binary systems. Up to now, astronomers had confirmed the detection of 14 circumbinary planets — ones that whirl around both stars of a binary system at once.

"Circumbinary planets were originally thought not to exist, since the binary stars stir up the planet-forming disks, creating a harsh environment for planets to form," study lead author Matthew Standing, an astrophysicist at the Open University in England, told Space.com. "This all changed with the discovery of Kepler-16b in 2011 by the Kepler space telescope. This discovery showed that it must be possible for these planets to form."

Related: How common are Tatooine worlds?

Until now, just one binary system was known to host multiple planets — Kepler-47, located about 5,000 light-years away, in the constellation Cygnus, the Swan. This multiplanetary circumbinary system possesses a whopping three known worlds, Kepler-47 b, d and c.

In the new study, astronomers investigated the binary system TOI-1338, located about 1,320 light-years from Earth in the constellation Pictor. In 2020, NASA's exoplanet-hunting TESS space telescope discovered a circumbinary planet dubbed TOI-1338b orbiting TOI-1338's pair of stars.

Using the European Southern Observatory and the Very Large Telescope, both located in the Atacama Desert in Chile, the scientists tried pinpointing the mass of TOI-1338b. Despite their best efforts, they could not achieve that. Instead, they discovered a second planet.

"With only 15 of these circumbinary planets known out of the over 5,200 total exoplanets discovered so far, it is exhilarating to be a part of this emerging branch of exoplanet science," Standing said. "Our preliminary results show that circumbinary planets seem to exist as frequently as planets around single stars like our sun."

The newfound world is called BEBOP-1c, after the name of the project that collected the data, BEBOP, which stands for Binaries Escorted By Orbiting Planets. (BEBOP-1 is another name for the binary system TOI-1338.)

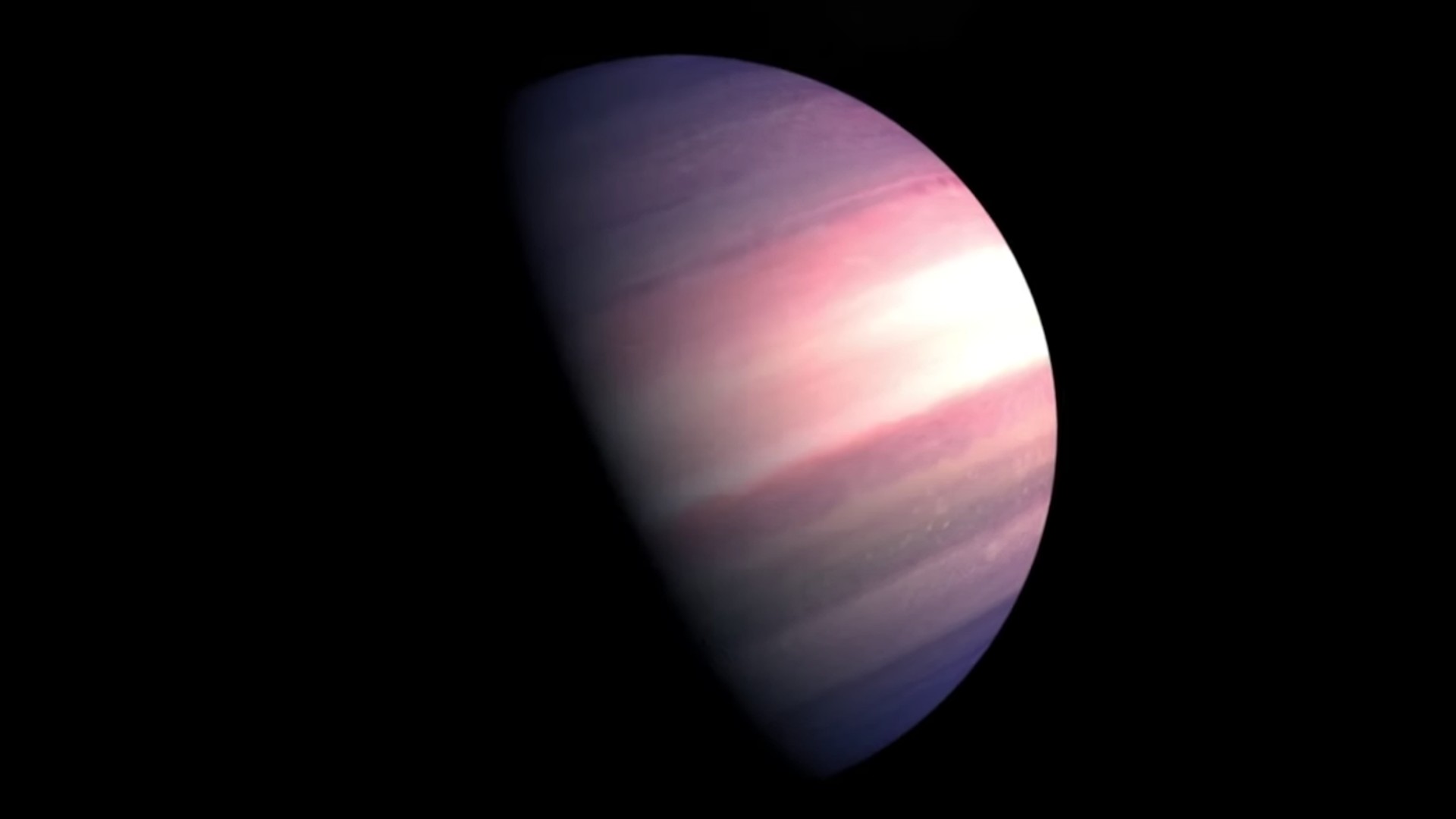

BEBOP-1c is a gas giant about 65 times the mass of Earth, and about five times less than Jupiter's mass. It orbits its stars at a distance of about 79% of an astronomical unit (AU) (one astronomical unit is the average distance between Earth and the sun), taking about 215 days to complete a voyage around its suns.

In comparison, TOI-1338b is located about 46% of an AU from its stars and takes about 95 days to orbit them. The scientists estimate it is at most 22 times Earth's mass.

Using the TESS space telescope, a high school student helped discover TOI-1338b when it passed or "transited" in front of the brighter of its two stars on several occasions. This helped the researchers estimate its size — about the same as Saturn — but not its mass.

In contrast, in the new study, the researchers were monitoring this binary system by looking for wobbles in the orbits of the stars. This "radial velocity" method can detect the gravitational tug of planets. The gravity of a planet is related to its mass, so this wobbling can help reveal how much a planet weighs.

BEBOP-1c is the first circumbinary planet detected with the radial velocity technique alone, study co-author Amaury Triaud, an astrophysicist at the University of Birmingham in England, told Space.com. Its discovery would have come earlier — COVID led to temporary closures of the observatories that helped detect BEBOP-1c, delaying these findings for a year.

"Until now, circumbinary planets have been discovered in transit by the Kepler and TESS space telescopes, which cost hundreds of millions of dollars," Standing said. This new discovery is powerful because it shows "you don't need expensive space telescopes to detect these planets." Instead, they can also be discovered using the radial-velocity technique "from ground-based telescopes with careful planning and target selection."

Detecting circumbinary planets with the radial velocity technique is difficult. The light from both stars can make it challenging to collect precise data on their motions to confirm the presence of circumbinary worlds, Standing explained.

"BEBOP gets around this problem by choosing binary stars where the secondary star is far smaller and dimmer than the primary star. This means that the secondary star isn't seen by our telescopes and so the two signals don't interfere," Standing said. "These types of binary star systems are rarer than ones where the two stars are of similar size, but with recent advancements in data analysis techniques, BEBOP will expand its search to planets around these equal-size binaries in the near future."

So far only two worlds are known in the TOI-1338/BEBOP-1 circumbinary system. However, more might be identified in the future, the scientists noted. Future research can also help confirm BEBOP-1c's size and TOI-1338b's mass.

"We have an ongoing survey with telescopes in France and Chile to find more circumbinary planets and measure their properties more accurately," Triaud said. "For instance, how often do they happen; are they the same or less or more massive than planets orbiting single stars; and so on."

Another important step "would be to measure the atmospheric chemistry of circumbinary planets and compare them to planets orbiting single stars," Triaud said. "Telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope are uniquely suited for it and these type of investigations would provide very novel evidence about planet formation."

The scientists detailed their findings June 12 in the journal Nature Astronomy.