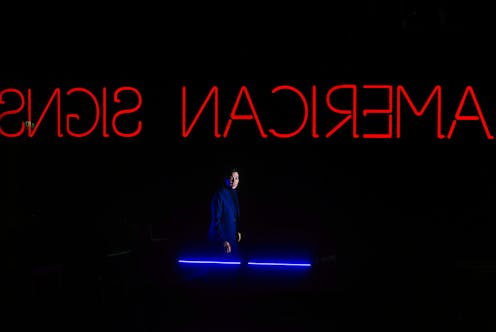

Anchuli Felicia King’s new one-performer piece, American Signs, written for the talented Catherine Văn-Davies, thrusts us into the world of a campus hire at “The Firm”, one of the “Big Three” consultancies in the United States.

Waiting to be either “right-sized” (one of the innumerable euphemisms for “fired”) or hand-chosen for a mission, the protagonist’s fortunes flip when she is told to pack: she’s accompanying her “very attractive and very married” superior to Ohio, where a struggling firm has been forced to call in the big guns.

She can stop compiling “dickstistics” (statistics on equestrian penises) and live to see another day, leaving her Pakistani colleague – deemed too upper-class and, as we shall learn, of the wrong ethnicity to be seen as fuckable by the boss – to the “glue factory”.

The horsey theme that runs through the play serves as an analogy for the human expendability consultancy firms rely on and reproduce. The consultants themselves are expendable, but more so are the workers whose lives they, literally, destroy.

If the former’s expendability is to be avoided, our protagonist must take the stun gun and put it, just so, between the horse’s eyes.

In 21st century capitalism, the consultant stands between the bosses and the workers, thus obscuring the process described by Marx in Volume I of Capital:

the more alien wealth they [the workers] produce, and […] the more the productivity of their labour increases, the more does their very function as a means for the valorisation of capital become precarious.

Nefarious consultancies

King, of Thai-Australian descent, gives her protagonist a Vietnamese identity, the daughter of a workaholic Ba whose sole dream was for his daughter to attend Stanford. She dutifully does, but he has another string to his bow: he breeds horses in Sacramento.

King wants us to know you cannot and should not pigeonhole Asian people. Nods to an abusive relationship with Ba bubble under the surface but go unresolved. We are never sure whether it’s this relationship that breeds the protagonist’s ultimate ability to park her moral qualms about her job in which “you are paid three times as much in one year as the average worker is paid in five”, or whether it’s the nature of consultancy itself.

Certainly, we are left with no ambiguity about the fact that consultancies are nefarious, relying on their employees’ ability to alienate themselves from the effects of their rationalising number-crunching. Except, that is, in their most secretly held thoughts (“I never said this”, Văn-Davies repeats when voicing her qualms).

But in this play we never get a complete sense of what the system is that requires consultancies. Capitalism slips away. In particular, racial capitalism lurks out of sight.

An American story?

King chose to set her play in the US. Management consultancy, after all, is an American invention and setting the play there allows for it to be easily produced outside Australia.

However, this choice also allows the problems it wishes to highlight to be seen as uniquely American signs, to riff on the title. Problems can be looked upon from the Australian vantage point as happening “over there”. This raises at least two issues.

As a worker at an Australian university, the setting felt incongruous. Last year, the Sydney Morning Herald reported Australian universities had ramped up their spending at consultancy firms including PWC, the subject of a Senate inquiry for its role in helping its clients avoid tax, at the same time as universities laid-off (“right-sized”) thousands of employees and engaged in large-scale wage theft. The play felt all too real, yet consultancies’ outsized influence on pubic institutions in Australia is not just a mirroring of US capitalism.

Secondly, the play’s Americanness and the protagonist’s Vietnamese identity collide to produce the comforting idea that race, like capitalism, isn’t (white) Australia’s problem.

That King wants to trouble the binary of white perpetrators and racialised victims is well-taken. Ultimately, her protagonist, while clearly exploited by sexualised racism, chooses to become the embodiment of the perfect consultant that the ruthless pursuit of accumulation at all costs requires.

King makes it clear capitalism wears many faces. However, this troubling of the binary stops at the door of Blackness: the beleaguered boss of the Ohio company she is sent to “downsize” is a Black woman whose accent is uncomfortably reproduced by Văn-Davies who, despite her myriad talents, can’t quite get it right. What then of the inextricability of capitalism and racism?

Making an Asian woman the face of consultancy, encapsulating the industry’s racism in the ethnic preferences of a slimy boss, and taking the heat off Australia’s own central role in racial-colonial capitalism are all choices I’d put to King.

Nonetheless, American Signs is entertaining and astute by all measures. If nothing else, you’ll learn plenty of ways to say, “you’re fired”.

American Signs is at the Sydney Theatre Company until July 14.

Alana Lentin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.