Researchers have identified a new species of ancient humans, which they have named Homo juluensis, meaning "big head," based partly on a very large skull found in China.

But what is this new species, and how does it help paleoanthropologists understand hominin variation in the Middle Pleistocene epoch about 300,000 to 50,000 years ago?

After our H. sapiens ancestors evolved roughly 300,000 years ago, they quickly spread out of Africa and into Europe and Asia. For decades, paleoanthropologists have tried to figure out how hominins were evolving prior to the arrival of modern humans, particularly between about 700,000 and 300,000 years ago, when multiple other early humans existed. For instance, anthropologists have found fossils from species like H. heidelbergensis in western Europe and Homo longi in central China, though not everyone agreed each of these represented a separate species. These fossils have also been lumped into catch-all terms like "archaic H. sapiens" and "Middle Pleistocene Homo," and are sometimes informally called "the muddle in the Middle."

Writing about the fossil hominin evidence from China in the journal The Innovation in 2023, Christopher Bae, an anthropologist at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, Xiujie Wu, a paleoanthropologist at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and colleagues wrote that continuing to use these catch-all terms has hindered attempts to fully understand the evolutionary relationships among our ancestors.

Related: Strange, 300,000-year-old jawbone unearthed in China may come from vanished human lineage

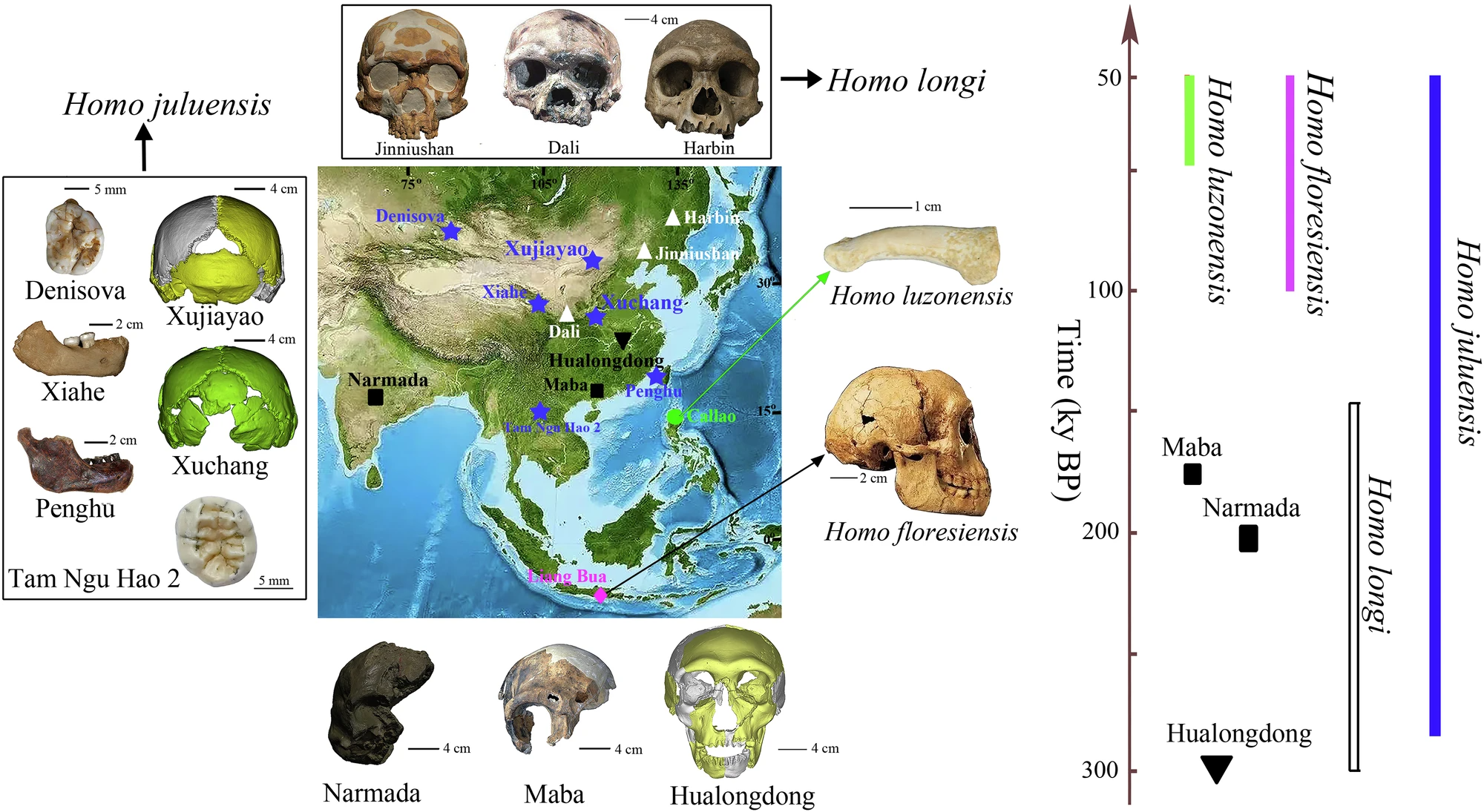

In a study published May 2024 in the journal PaleoAnthropology, Wu and Bae described a set of unusual hominin fossils that were found decades prior at Xujiayao in northern China. The skull was very large and wide, with some Neanderthal-like features. But it also had traits common to modern humans and to Denisovans.

"Collectively, these fossils represent a new form of large brained hominin (Juluren) that was widespread throughout much of eastern Asia during the Late Quaternary [300,000 to 50,000 years ago]," they wrote.

Now, in a commentary published Nov. 2 in the journal Nature Communications, Bae and Wu say that the growing fossil record in east Asia requires new terminology. Splitting "archaic Homo" in this area into at least four species — H. floresiensis, H. luzonensis, H. longi and the newly named H. juluensis — will help researchers better understand the complexity of recent human evolution, they argue.

The newly named H. juluensis is based on fossils that date to between 220,000 and 100,000 years ago from Xujiayao and Xuchang, a site in central China. In 1974, excavators discovered more than 10,000 stone artifacts and 21 hominin fossil fragments representing about 10 different individuals at Xujiayao. All of the cranial bones show that these hominins had large brains and thick skulls. The four ancient skulls from Xuchang are also very large and similar to those of Neanderthals.

In looking at the mixture of traits present in these groups of fossils, Wu and Bae decided in the May 2024 paper that "they represent a new hominin population for the region, namely Juluren, meaning 'large head people'."

Although H. juluensis is taxonomically a new hominin species, that does not mean they were genetically isolated. They may have been the product of mating between different types of Middle Pleistocene hominins, including Neanderthals, they wrote, "supporting the idea of continuity with hybridization as a major force shaping human evolution in eastern Asia."

Although H. juluensis is not yet commonly accepted, the name is growing on experts.

"Names are important both in evolutionary biology and in anthropology. A name is a mental tool that enables us to communicate with other people about a concept," paleoanthropologist John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin–Madison wrote in a June 16 blog post. "I see the name Juluren not as a replacement for Denisovan, but as a way of referring to a particular group of fossils and their possible place in the network of ancient groups."

Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science in an email that his own work with Chinese colleagues suggests the H. juluensis material may actually fit better with H. longi. "I don't think having a large cranium is a very useful defining characteristic," he said. "However, Xuchang certainly does seem different, with more Neanderthal-like traits, so its classification is less certain."

In a statement, Bae said that naming a new species helps clarify the fossil record, particularly in Asia. "Ultimately, this should help with science communication," he said.