Ever since H.G. Wells published The Time Machine in 1885, science fiction has served as a not-so-secret way to unpack problems of social class. Today, we tend to think of these sorts of tales as “anti-capitalist,” insofar as the plot directly addresses the injustices of a class system that separates people into the “haves” and the “have-nots.”

In the far future of The Time Machine, it’s not very subtle. The Morlocks are literally eating the Eloi. With his far-future dystopia, Wells darkly suggested that the problems of a capitalistic hierarchy are inescapable, with half of the human race destined to be consumed by the other.

Other vaguely anti-capitalist sci-fi, like the Star Trek franchise, suggests a post-scarcity future in which humanity (mostly) exists without massive social class issues. But what happens in between these possible futures? Whether we end up in the Trek future, or the Wells future, when is that struggle most relevant? One answer can be found in the underrated 2013 Neill Blomkamp film Elysium. For those interested in how a contemporary sci-fi film can split the difference between utopia and dystopia, this movie is worth another look.

Lucky for you, it just landed on Netflix. Here’s why Elysium is worth watching (or rewatching) and what you should know before you press play.

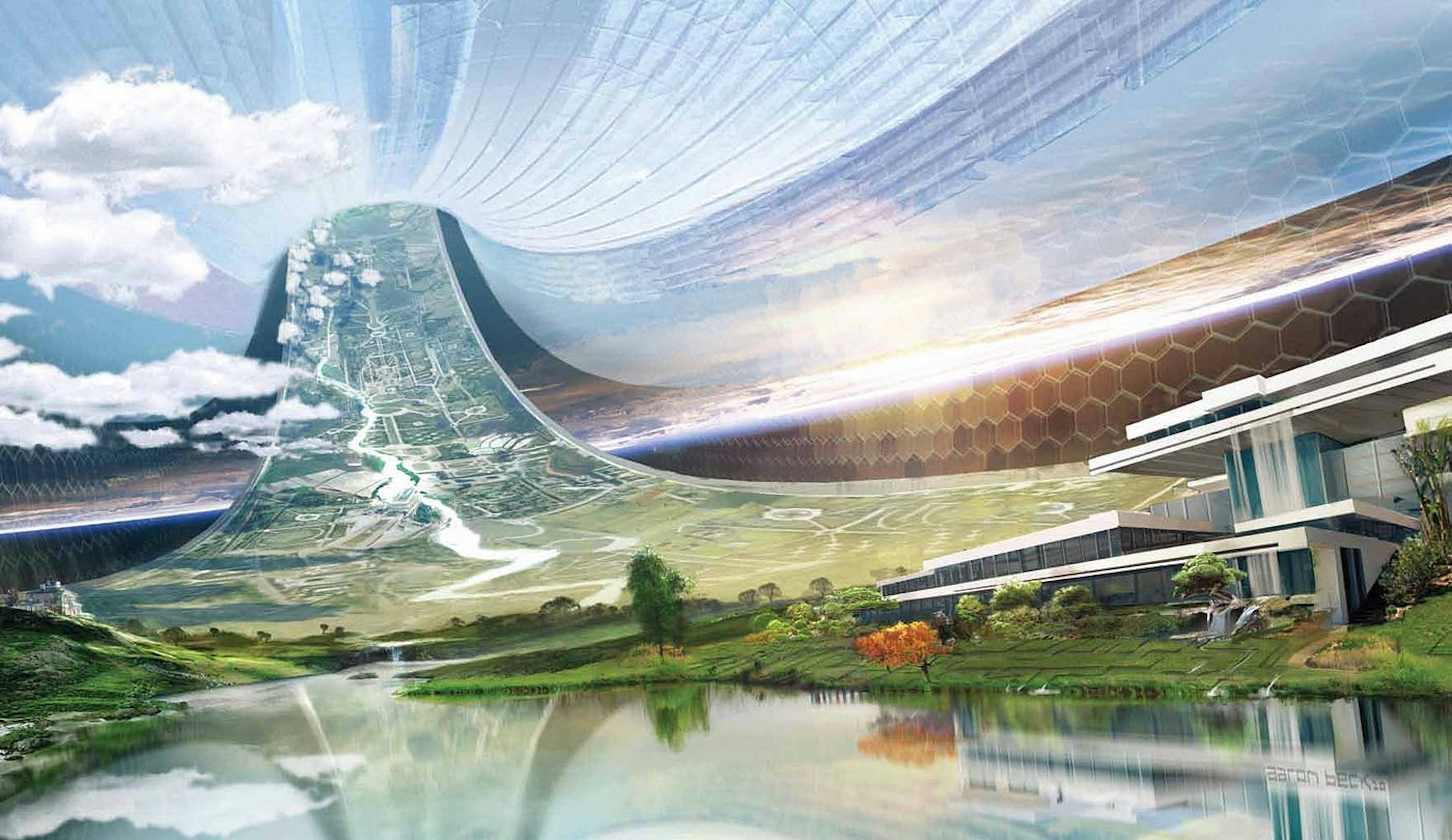

Elysium depicts a near-future Earth in which the majority of rich and privileged humans have migrated to an orbiting space station which gives the film its title. The city-state hogs the advanced medical resources of Earth, leaving the people on the planet below in a perpetual state of lawlessness and impoverishment. Matt Damon stars as Max Da Costa, a former criminal who, while doing dangerous work, is exposed to a lethal dose of radiation, giving him just five days to live. He soon obtains an exo-suit to augment his failing body. It’s then discovered that Max has data hidden in a chip in his brain that can, in theory, alter the computer systems running Elysium, which will benefit all the people who don’t live there.

Essentially, Elysium’s plot relies on a down-on-his-luck Matt Damon embroiled in cyberpunk mumbo-jumbo that only barely makes sense. Like many of Neill Blomkamp’s provocative sci-fi movies (District 9, CHAPPiE), the key to enjoying Elysium is to favor vibes over logic. Why Max can reboot the entire space station only makes sense because the movie needs it to. Similarly, the main antagonist of the film — the assassin/black ops agent Kruger (Sharlto Copley) — is depicted as overly sadistic and motivated to defend the status quo because his evilness needs to be extremely clear.

But Elysium balances out some of its on-the-nose moralistic tendencies with smart bits of subtly. Jodie Foster’s performance as Delacourt, the legitimate public administrator of Elysium provides the film with chilling realism. Yes, Kruger might be an over-the-top murderer, but he’s been hired by the well-mannered, prim, and proper Delacourt. In a sense, she’s the real villain of the movie, not in action, but by what she represents. Elysium reminds us that elitism comes in various guises, and that conflicts between working-class people often benefit the wealthy, regardless of the outcome. In a sense, despite being objectively evil, Kruger is as much a victim of the system as Max and his allies.

All of these components work together perhaps better than they should, even if the movie does create some discordant thematic elements. Without spoiling the ending, most sci-fi fans will find the solution to the overall conflict a little too easy, or at the very least, too sudden. But Elysium makes up for these flaws with a great supporting cast, including stand-out performances from Diego Luna as Max’s BFF Julio, and Alice Braga as Frey, a single mother trying to care for a daughter with cancer.

Frey’s story ultimately becomes the driving force of the entire film. Max needs to get the advanced technology from Elysium to save her daughter. And toward that end of Elysium, nothing else matters.

The downtrodden characters in Elysium are easy to root for, even if it sometimes feels like Blomkamp is using Hallmark movie shortcuts to make it all work. But again, the performances from everyone involved sell this movie on every level. We’re currently in a sci-fi renaissance of both Diego Luna (Andor) and Alice Braga (Dark Matter) and it’s fun to rewatch Elysium now, realizing how much these performers have contributed to the genre since. Thanks to Contact, Foster’s sci-fi cred was well established before Elysium, but it's refreshing seeing her play against type here, even if her screentime isn’t as long as fans might prefer.

In short, Elysium feels like the kind of big sci-fi movie we don’t see much anymore, at least not in theatrical releases. Today, it’s easier to imagine this as a one-off episode of Black Mirror or a long-drawn-out multi-episode epic on Apple TV+. But what’s nice about Elysium is that it neither overplays its themes nor overstays its welcome. For a movie concerned with the distribution of wealth, the film refreshingly balances the good with the bad in equal measure. It’s tempting to say they don’t make them like this anymore, but the truth is, nobody made movies quite like this, before either.