A series of memorials commemorating the worst instance of racial violence in Chicago history that have yet to be installed on city streets are now temporarily on view as part of a neighborhood art gallery’s final exhibition.

The memorials recall the Chicago race riots of 1919, where for an entire week gangs of white Chicagoans terrorized their Black neighbors, who also fought back. In all, 38 people died, and at least 537 were injured. Of those killed, 23 were Black.

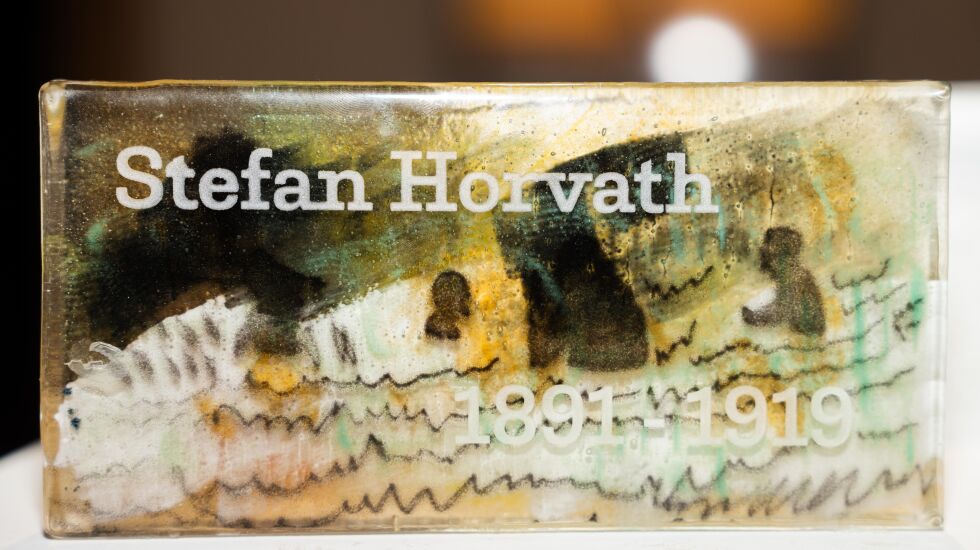

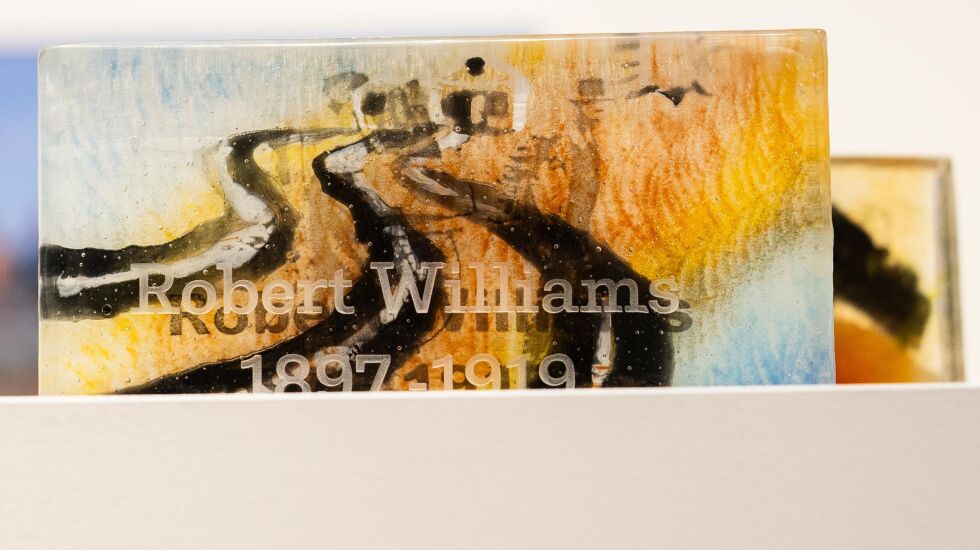

Outstanding questions about how to weatherproof the memorials — brick-shaped pieces of layered glass honoring the life of each person killed — have kept them from being installed at the scenes of the violence from over 100 years ago.

For now, they’re the centerpiece of “Disarm, Everyday Violence, Every Day,” the outgoing exhibition of the Weinberg/Newton Gallery in the West Town neighborhood.

“We wanted something that focused on Illinois and specifically Chicago,” said gallery owner David Weinberg, “and that would address one of those issues at the top of the list in Chicago, which is gun violence and the reasons for the gun violence.”

The memorials were made by Firebird Community Arts, a West Side organization that teaches glass blowing to victims of gun violence as a way to help them recover. The group has been developing the memorials since 2020.

There are two organizations partnering with the gallery on the final show. The other is the Gun Violence Prevention PAC, a political action committee that Weinberg said played a role in passing the recent assault weapons ban in Illinois.

Weinberg considered the two organizations “bookends” for the issue of violence in Chicago, with one looking at solutions and the other looking at root causes.

The exhibition will be on view at the gallery — open Thursday through Saturday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. — until Sept. 9, when the gallery will hold a closing party.

Seated in his office at the gallery, Weinberg admits to being something of a “news junkie” and the closing exhibition isn’t the first that the gallery has done on a pressing issue.

“We’re always trying to be very relevant with our exhibits,” said Weinberg, 79, whose office is filled with artwork he’s made based on social justice issues. One piece juxtaposes headlines from daily newspapers with images from television news during the protests over the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Another piece, a diptych, shows the daily news headlines that Weinberg views as transitory problems and those that, in his view, pose an existential threat to the country.

Weinberg has been able to spread that message of awareness of social issues through art by pairing with different nonprofits focused on various social justice issues.

Past shows have included “For Those Without Choice,” a show with Planned Parenthood on abortion access, and “Can you see me?,” made with SkyART’s Just-Us, an organization that tries to help incarcerated youth.

“I had this feeling that as effective as they were at getting this message out, very rarely did they use the avenue of art,” Weinberg said. “I have this belief that putting something in an art form is much more digestible than a straight story.”

Weinberg who, along with his wife Jerry Newton, has run the gallery out of his own pocket, said they always knew that closing was always a matter of time as he never wanted to go through the process of looking for donors to support operations.

“We had a good run,” he said.

Past shows have drawn the ire of some people and at least one protest, Weinberg said, but the reward has come in bringing people together.

“There aren’t that many jobs where everybody you interact with is focused on social justice,” he said. “I’ll really miss that.”

Weinberg’s mission of using art to talk about social justice issues also inspired Peter Cole and Franklin Cosey-Gay to start the Chicago Race Riots of 1919 Commemoration Project in 2019.

Cosey-Gay, director of the University of Chicago’s Violence Recovery Program, asked Firebird to create the memorials.

Five bricks are on view, commemorating victims Stefan Horvath, Casmere Lazzeroni, John Walter Humphrey, Robert Williams and William Otterson. Firebird executive director Karen Reyes said they were chosen because they are among the first completed.

The gallery exhibition is the latest thing the group has planned to highlight the history the events of over a century ago, which they say is a cause of the city’s ongoing segregation and violence.

On July 22, the commemoration project plans a bike tour of the sites of the violence and on July 27, a performance art piece by Lookingglass Theater at the 31st Street Beach, near the site where the first victim, Eugene Williams, died.

Williams, 17, and four friends launched a raft from the 26th Street Beach. When they strayed too close to “whites only” waters, a white man, George Stauber, threw rocks at the raft until Williams fell into the lake and drowned.

An installation at the exhibition shows a room filled with sand, and a rope, representing the invisible “color line,” stretched across it. It includes photographs of Firebird participants reclaiming the beach where the violence began by enjoying a day there.

Reyes said much of the project has been about victims of gun violence “addressing and facing trauma.” The beach day was the opposite, a chance “to spark joy and to create space to be young and joyful and not only think about the worst things that happened to them.”

Michael Loria is a staff reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times via Report for America, a not-for-profit journalism program that aims to bolster the paper’s coverage of communities on the South Side and West Side.