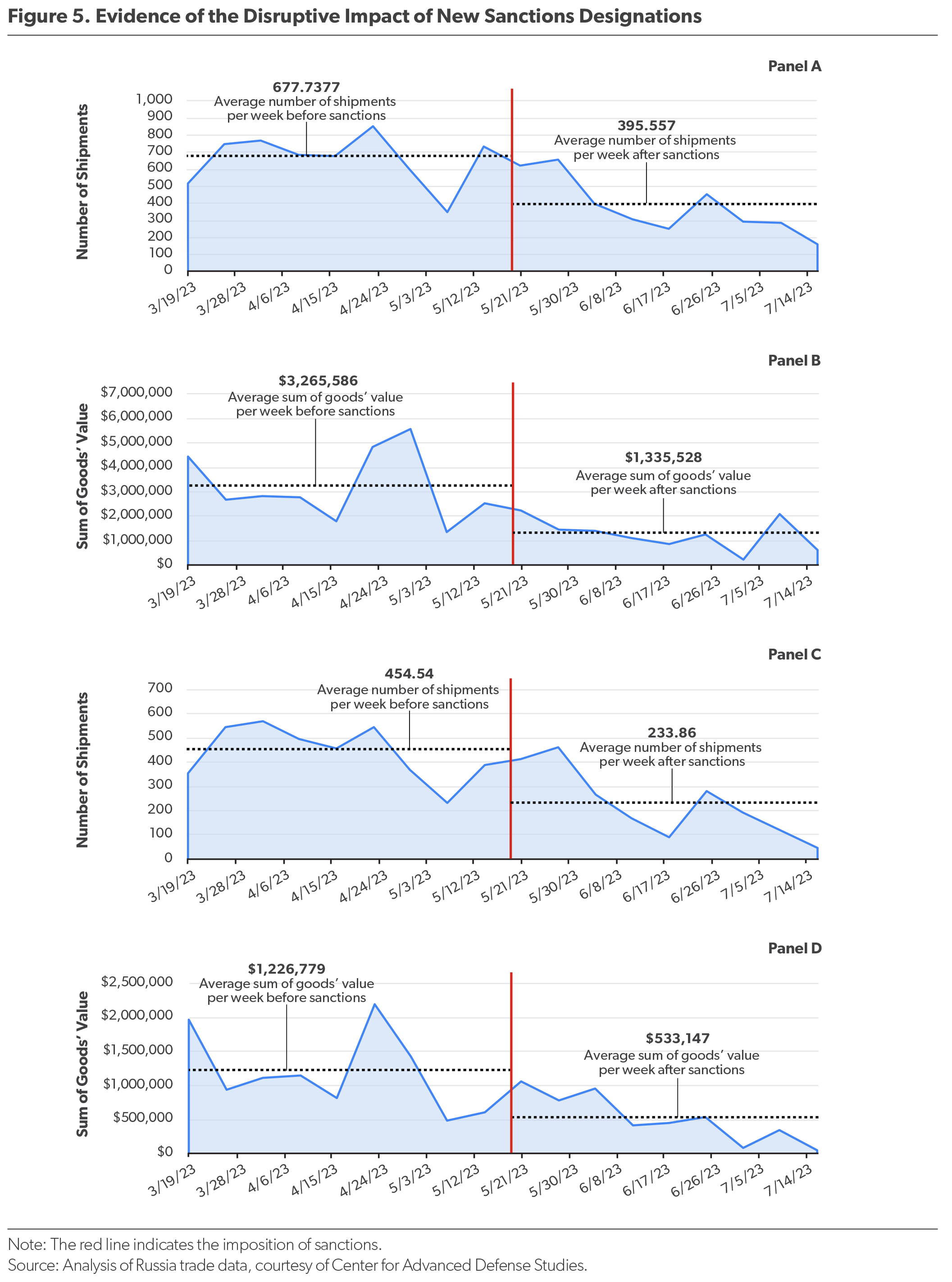

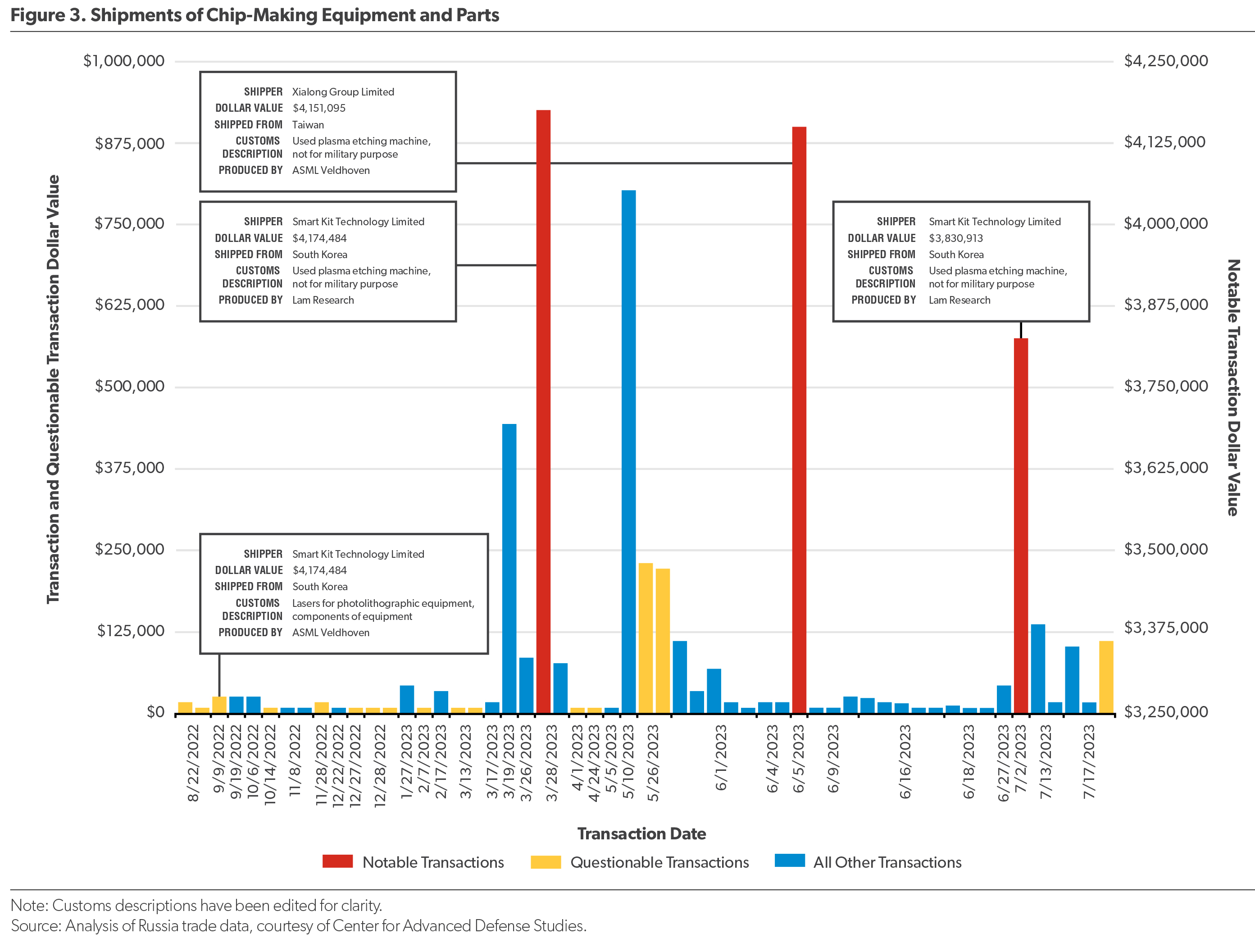

The sanctions imposed following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine aimed to disrupt Russia's military capabilities by limiting its access to advanced chips are working, as Russian entities can no longer get chips directly from American, European, Japanese, and Taiwanese companies. Despite these efforts, Russia continues to obtain advanced processors mainly through indirect channels, primarily involving Chinese distributors, who now control 89% of the market, according to a report from the American Enterprise Institute.

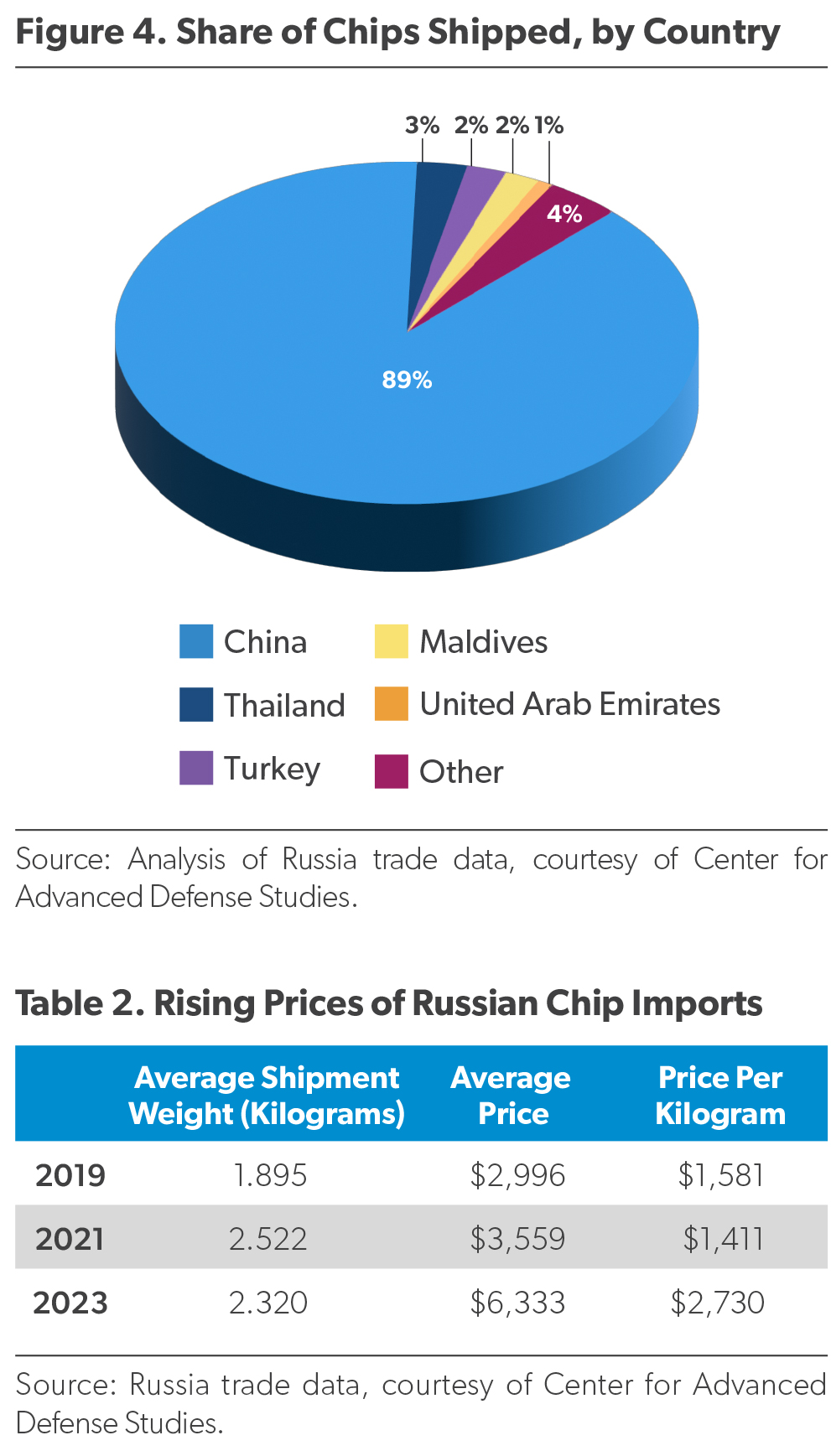

The sanctions have forced Russia to pay nearly double for semiconductors compared to pre-war prices due to the need to establish new, covert supply chains. The company paid $1,411 per kilogram of chips in 2021 and had to pay $2,730 per kilogram in 2023. Notably, about 89% of semiconductor products Russia acquired since the onset of the conflict have been sourced from China. Surprisingly, Russia even obtained some chipmaking equipment from South Korea and Taiwan.

Chinese distributors, essentially operating in a grey area of international laws, have continued to supply Russian buyers with Western-designed chips after all major companies and countries cut their ties with Russia (not that we were surprised). This process circumvents direct sales bans by routing the transactions through China, where enforcement of these sanctions is laxer, thus maintaining a steady flow of technology into Russia. Due to the U.S. sanctions, neither China nor Russia can lay their hands on advanced processors for AI and HPC, such as Nvidia's H100, at least in mass quantities.

Additionally, Russia employs the so-called transshipment strategies involving other nations, such as Turkey and the United Arab Emirates, which act as intermediate points for high-tech deliveries, the report says. Entities in these countries receive the initial shipments and then forward them to Russia, effectively masking the ultimate destination and complicating the enforcement of export controls. Based on what we know, such tactics allowed access to chips used in military equipment and technology used by Russian consumers.

Before the sanctions, Russia sourced its semiconductors through three major avenues: direct imports from Western companies, which includes both direct imports by companies like AMD and Intel as well as sales by major distributors, such as Ingram Micro; Russian-designed chips manufactured abroad, primarily by TSMC; and a small domestic production mainly serving the defense sector. Post-sanctions, direct imports have been severely restricted except for covert routes through countries like China and possible secret manufacturing agreements with Chinese contract makers of chips, such as SMIC and Hua Hong.

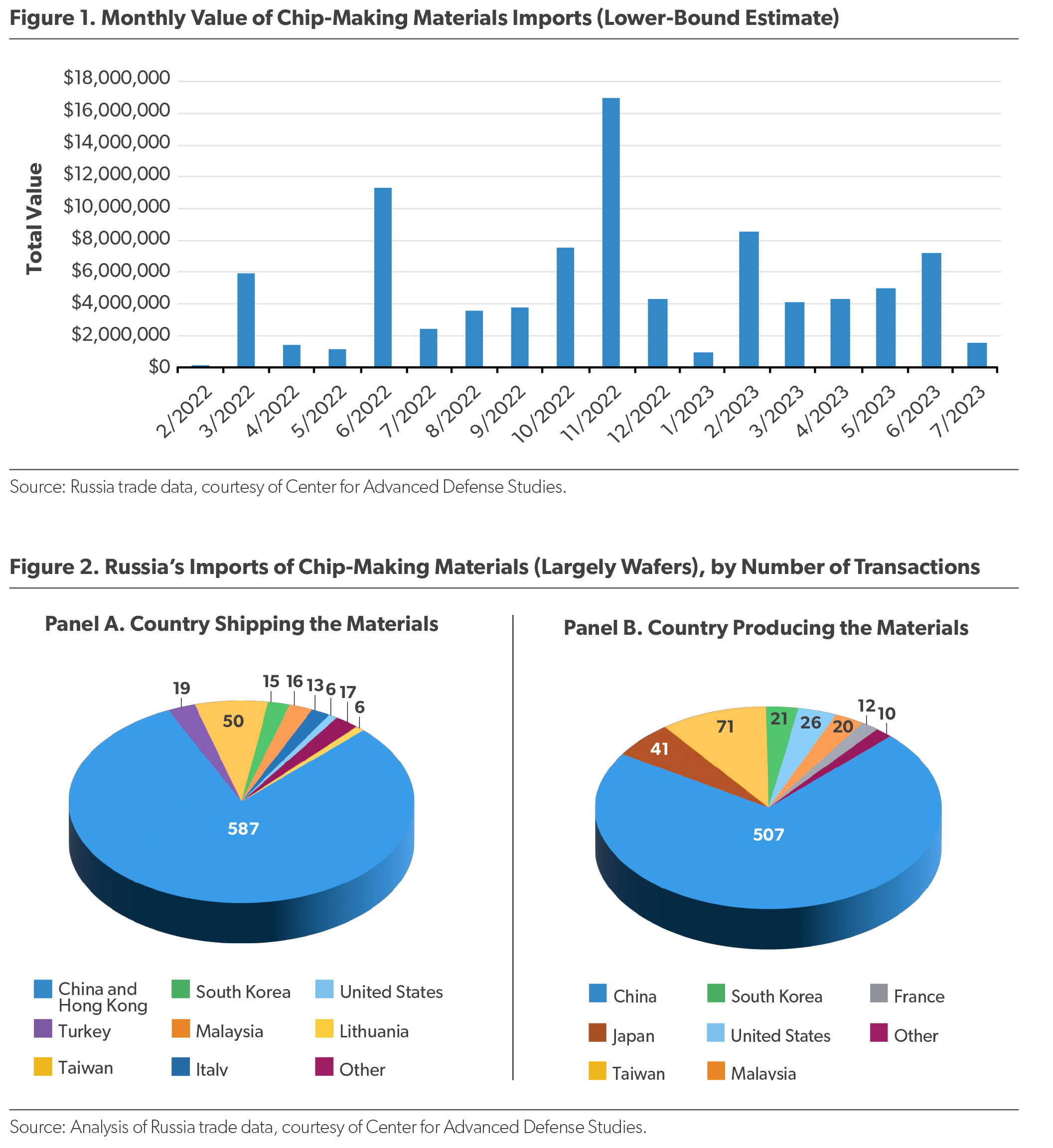

Meanwhile, AEI claims that Russian domestic chip manufacturing remains way too outdated and is limited to serving the defense industry at best. Manufacturers like Angstrem and Micron are heavily reliant on outdated wafer fab tools produced in America and Europe, which is why they have struggled to increase production in the face of sanctions that cut off their access to essential foreign equipment and materials. However, Russia has managed to get some wafer fab tools from countries known to be U.S. allies.

The report advocates for a new, multilateral export control regime that includes strengthened enforcement mechanisms and recommends involving all U.S. allies to ensure a more cohesive and effective approach to semiconductor export controls. Meanwhile, China is not exactly a U.S. ally but remains a major trade partner.